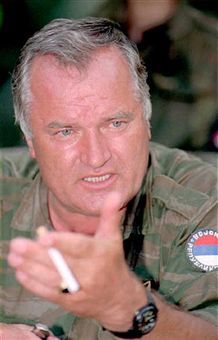

As Ratko Mladic faces his accusers at the Hague, it’s instructive to revisit the fallout from one of the

atrocities he is alleged to have committed. The Srebrenica massacre was both a horrendous tragedy and a horrendous failure of internationalism – a point the Spectator made cautiously as news

of the war crime emerged.

As Ratko Mladic faces his accusers at the Hague, it’s instructive to revisit the fallout from one of the

atrocities he is alleged to have committed. The Srebrenica massacre was both a horrendous tragedy and a horrendous failure of internationalism – a point the Spectator made cautiously as news

of the war crime emerged.

No End of a Lesson, The Spectator, 22 July 1995

The tragedy in Bosnia is so harrowing, the United Nations’ failure so all-embracing, the West’s humiliation so total that it is difficult as yet to see beyond them. But for the Bosnians themselves, the worst may now be passed.

Whether the defeated international powers stage some dramatic military feat before their departure is largely irrelevant to those they were sent to protect. For many months the Bosnians have realised that they would have to fight their own battles. Having now written off the eastern enclaves which the UN was pledged to defend, the Bosnian government’s only wish now is to see the arms embargo lifted under conditions which ensure a rapid build-up of arms from the United States (as the Spectator has been arguing since January 1993). In this they will probably be lucky, which opens up some hope for Bosnian families and children.

For the rest of us, the implication of the Bosnian tragedy will continue to reverberate, though with a distinctive timbre for different interests. Bosnia will confirm in the minds of isolationist conservatives in the USA and, increasingly, Britain that foreign military ventures inevitably involve unacceptable risks. It will suggest to the Europeans that Britain is now a country whose forces will not fight, and that Franco-German military co-operation therefore makes more sense. It will convince the Islamic world, which has seen its pleas and threats ignored, as Muslims were exterminated in the heart of Europe, that there is nothing to gain from co-operation with the West and nothing to fear from defying it. And it will persuade the Russians that no limits exist beyond which challenges to borders, minorities and international agreements involve serious risks. Each of these suppositions is wrong – so wrong as to threaten consequences still more catastrophic than have already occurred in Bosnia; but each will in its own way seem persuasive.

The real lesson for the West (and indeed the wider world) which flows from the Bosnian debacle is different. It is that only nation states, not international bodies, can take decisive action to prevent, deter or reverse aggression. The present fiasco, brought about by confused chains of command, bureaucrats taking military decisions and generals taking political ones, shifting and over-restrictive rules of engagement and mutual buck-passing and recrimination, fully exemplifies what can be expected of international attempts to wage war by committee. It is in obvious contrast with the way in which other successful military operations were mounted. The campaign to reverse Argentinean aggression against the Falklands would and could never have been undertaken by international action, even though it required some international acquiescence. The Gulf war only succeeded – insofar as it succeeded – because it was American-led, albeit with British and French support. It is only in the present era of utopian internationalism that anyone would have expected the likes of Boutros-Boutros-Ghali and Yasushi Akashi to take strategic decisions or a gaggle of commanders from every continent whose troops could not communicate with one another to implement them.

Nor is it just at the operational level that such determined internationalism is an absurdity. At the political level also it is simply not possible for national politicians to explain to domestic audiences why their own soldiers should be sacrificed at the instance of international authorities with exclusively international objectives. The bitter ridicule which greeted Vice-President Al Gore’s tribute to 15 Americans killed in Iraq as ‘those who died in the service of the United Nations’ reinforced that lesson for American politicians. But it is far from clear that their European equivalents have yet received the message.

It may be some time before the UN is again entrusted with peace-keeping (let alone peace-making) responsibilities. But the Europeans remain unabashed. The European Union was not conspicuous by its success in dealing with the problems of the former Yugoslavia – though by common agreement it started out by being regarded as ‘Europe’s problem’. The Maastricht Treaty, however, envisaged a common European foreign and security policy leading a common defence policy and perhaps common defence. This is still the goal, as will be revealed at the forthcoming Inter-Governmental conference.

Theoretically it might work. If the full-blooded federalists got their way and managed to create a genuine political identity out of the European national states, then a stable defence identity could ultimately follow. But this is hardly likely in the foreseeable future. Instead, structures and realities will grow yet more out of joint with one another. The credibility and reliability of European countries’ defence commitments will be still further reduced. And the result could be other Bosnias – with international bureaucrats directing confused military operations in support of ill-defined objectives on Europe’s borders. Ensuring that Britain avoids that fate should provide a new suitable and satisfying challenge to our new eurosceptical defence secretary.

Comments