G and T, the favoured cure for gyppy tummy in Himalayan hill-stations, bubbled home from the Raj to the English suburbs to become the aperitif of choice in Betjemanic golf clubs and panelled bars from Altrincham to Carshalton. There is a particular pleasure in being in a London pub at the end of an office day, and hearing the clink of ice in glass, as barmaids ask ‘Do you want lemon in that?’ and office workers, happy that the tedium of toil is done, say, ‘Yes, and make those doubles.’

Larkin wrote about the pleasure of making G and T, but it was never my drink. Gin, for me as a boy, was the smell of gin and dry vermouth on my father’s moustache as he embraced me — a delicious aroma which I associate with fun, and the comforting sensation of being loved. I also associate it with that postwar England into which I was born, in which middle-middle-class people like us seldom drank wine with meals, but the grown-ups got tanked up on spirits and cigarettes before supper.

It was a joy to me when I discovered that, of course, you do not have to mix gin with anything. It tastes very good on its own, or with a dash of water. Even the cheapest stuff from supermarkets tastes good. I do not know if the ‘Gordon’ in George Gordon Byron had anything to do with the gin people, but he was a gin-drinker, and drank gin and water while writing ‘Don Juan’. Angostura Bitters should be added sparingly to make the drink perfect, but they are not essential. (The nicest version, procured for me by Nicky Haslam, is Peychaud’s Aromatic Cocktail Bitters). ‘Gin and Bitters’ is the tipple of Jobber Skald, the hero of one of my favourite novels (sometimes entitled Weymouth Sands).

One of the many blessings brought to England by William of Orange was the Dutch habit of gin-drinking — though ‘hollands’ and English gin were always different: English gin is prepared with a highly rectified spirit, whereas Dutch gin had no preliminary rectification, and was made from a fermentation of mashed barley or rye, with the addition of juniper berries.

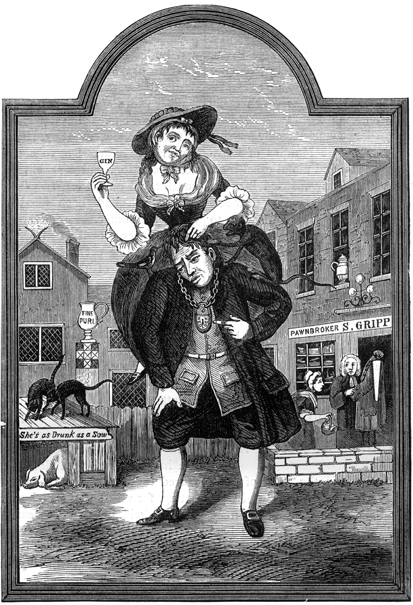

The point of gin-drinking is to get drunk. The toothless hags of Hogarth’s Gin Alley, and the leathery old expats in Noel Coward’s ‘bar in the piccola marina’ had the same sensible idea. That is why gin connoisseurship always strikes me as a bit rarified. Those who ‘prefer’ Bombay Sapphire or Hendrick’s are surely kidding themselves, for after the second glass, the effect is the same, and they are unlikely to be able to tell the difference between the finest Plymouth gin and the litre bottle of Sainsbury’s own. Not that taste is immaterial. Those of us who like gin wallow in the juniper bouquet when we first open the bottle. Labels are suggestive to the taste-buds, which is perhaps why the beautiful Gordons-for-export bottles, emblazoned with juniper berries against a yellow background, seem to contain ‘better’ gin than any other.

A famous porter during my boyhood had the advertisement ‘Guinness Is Good for You’. Gilbeys should have countered with ‘Gin Is Bad for You’, to see how many more bottles of the stuff they could shift. (Gordon’s tried a version of this by putting Bad Boy Gordon Ramsay on their posters).

Gin is the essential English drink in two senses. It just happens to be a drink which has been plentifully manufactured here, and enjoyed here for centuries. But it is also a great social indicator — highlighting an attitude not merely to drink but to life itself. For those of us who like gin, the point of it is blindingly obvious — that a few swigs make you woozy, far quicker than wine or beer will do. Moralists, on the other hand, will immediately start tut-tutting, either on the Stoic ground that we should be prepared to stare horrors soberly in the face, or on the even more nannyish ground that we might be damaging our livers, brains, guts or some other part of our anatomy in which they presume to take an interest.

Mr Gladstone was the classic example of the political busybody who wanted to ‘improve’ the life of persons of whom he disapproved. The Victorian working classes, quite naturally, drank gin to forget the horror of their existence. Gladstone wanted them to drink claret, as he had done since he was an undergraduate at Christ Church. Although you can still see ‘wine lodges’ up in the north of England — vestiges of this interfering habit of mind — it is reassuring to know that Gladstone’s aim was such a resounding failure.

The English educated and political classes still fall into the categories of those who Know Best — and who want to impose their austere tastes on everyone else — and those who feel it is no business of theirs to boss and control smokers and drinkers and druggies. Tony Blair — long before the invasion of Iraq — showed himself in his true colours by making a public announcement that we should not give money to beggars in case they spent it on some substance of which he happened to disapprove. It was almost an exact echo of the prig who asked Dr Johnson, ‘What signifies giving halfpence to beggars? They only lay it out in gin or tobacco.’ Johnson spoke for Liberty and England when he trenchantly replied: ‘And why should they be denied such sweeteners of their existence? It is surely very savage to refuse them every possible avenue to pleasure reckoned too coarse for our own acceptance. Life is a pill which none of us can bear to swallow without gilding.’

I think of this with satisfaction as I crack open a bottle of gin. That distinguished gin-lover Mrs Gamp spoke for all of us: ‘ “Mrs Harris,” I says, “leave the bottle on the chimley-piece, and don’t ask me to take none, but let me put my lips to it when I am so dispoged, and then I’ll do what I’m engaged to do.” ’

Comments