Washing a million crisp, cocaine-tainted banknotes is no easy feat these days. Walk up to a teller and attempt to deposit them in a bank and there’s a good chance you’ll be turned away and the police called.

You could, I suppose, call Saul, your friendly diamond dealer, and try to wash your ill-gotten gains through precious stones, but fencing those diamonds at close to what you paid for them will prove immensely difficult.

Although ‘bitcoin facilitates money laundering’ is a common refrain, enlightened ‘hodlers’ — as people who own bitcoin for the long term are known — understand that it’s a terrible way to launder money. For a start, bitcoin transactions are recorded on an open public ledger.

So what’s the name of the best money-laundering game in town? That’s an easy one: property.

Take Hong Kong, which is where China launders its money, and America, which is where the world launders its money. It’s easy to use property to clean dirty money in both.

This is because the governments of America and Hong Kong pretend to take the prevention of money laundering seriously just as they set up systems to facilitate it. Property is one such system. Let me explain.

Make no mistake, Chinese people have zero illusions about the rapacious nature of their government. While many Chinese (particularly corrupt officials) have benefited handsomely over the past 30 years by playing the political game well, they know one misstep could send them back to the countryside penniless. Beijing, should it want to, can completely bankrupt a Chinese citizen on a whim, with absolutely no due process. For this reason, wealthy Chinese need to keep their noses clean and their money stashed.

Put yourself in the shoes of Zhou, your average criminal dollar millionaire from China. How can he clean his loot while keeping it from the all-seeing gaze of President Xi Jinping?

On the surface, laundering money in Hong Kong shouldn’t be as straightforward as it is. Thanks to the Common Reporting Standard, or CRS (an American idea, incidentally), which came into practice in 2014, any time it likes, China can request that Hong Kong hand over near-comprehensive financial information about any Chinese national with money there. But what it can’t discover, thanks to a loophole, is information relating to property assets. Those details are off limits to Beijing.

Unsurprisingly, then, shortly before the CRS became a reality, Chinese nationals rushed to park money in Hong Kong real estate. As a South China Morning Post article from the time noted: ‘Hong Kong has been considered a tax haven for many mainland investors as there is no capital gains tax levied here. But now they are being forced to convert those financial investments into property, prior to the July deadline, to avoid declaring any financial assets held abroad to the Chinese authorities.’

Why would Hong Kong wish to keep its property register hidden from prying Chinese eyes? Well, property is a fantastic generator of economic activity. A property boom creates jobs and a government that increases property stock looks economically competent. But the converse is also true: a property slump causes big problems for a lot of people. By making it as easy as possible for Zhou and his friends to keep their money stashed in Hong Kong, the territory’s government ensures demand increases. Everyone wins (or seems to).

But Zhou might just as well look to America to launder his cash, as might anyone with dirty money. Because, despite coming up with the idea for the CRS and persuading more than 100 countries to sign up to it, America itself is not a signatory.

What’s more, in the United States, property enjoys a strange relationship with anti-money laundering financial reporting regulations. Only last year, the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network pointed out anyone could buy a property in Manhattan through a shell company without having to disclose his or her identity, as long as its value was under $3 million. The same could be done in Brooklyn, Queens, the Bronx or Staten Island for properties worth up to $1.5 million. And in San Diego, Los Angeles, San Francisco and other parts of California, properties could be purchased anonymously up to a value of $2 million.

For Zhou, then, American property has long been a superb destination in which to hide cash from Beijing’s prying eyes, or indeed from those of any government bent on stemming capital flight. As long as those investment limits were observed, anyone could expect to have little difficulty obtaining a clean bank account and making a property purchase in cash.

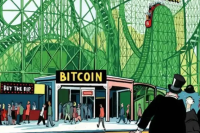

Now, let’s consider what it would take to launder money using bitcoin, which has lately gained notoriety as the world’s favourite monetary bogeyman. Let’s say you wanted to move a million dollars of dirty money into bitcoin. You’d have two options: you could either open an account on a spot exchange, or you could trade over the counter with a dealer.

Any exchange that could process a trade of this size would have to involve significant banking relationships. Any bank happy to take this money would have extensive anti-money laundering protocols in place: it would expect the exchange, should it be required by authorities, to present details of the customer. A sub-optimal situation for the would-be money launderer.

If you can’t use an exchange, you might try an over-the-counter dealer, but you would run into the same problems. These dealers have banking relationships — where else are they meant to put your million dollars? Banks will require them to know their customers. That means you will be asked about the source of your wealth. Of course, you might find a dealer who will ask no questions, but the commission you will pay as a result will be extremely aggressive. Losing 20 per cent of your cash in order to clean it does not make sense when there are better alternatives, like property.

Whatever is said in the media, washing money through crypto capital markets is very hard to do if you are unwilling to supply detailed information about that money’s provenance, or unwilling to take a huge haircut on your principal. Property is far easier because vested interests, from governments to real estate brokers, want to help you. Mythical bitcoin creator Satoshi Nakamoto ain’t the world’s biggest illegal finance enabler. No, that’s Uncle Sam.

Comments