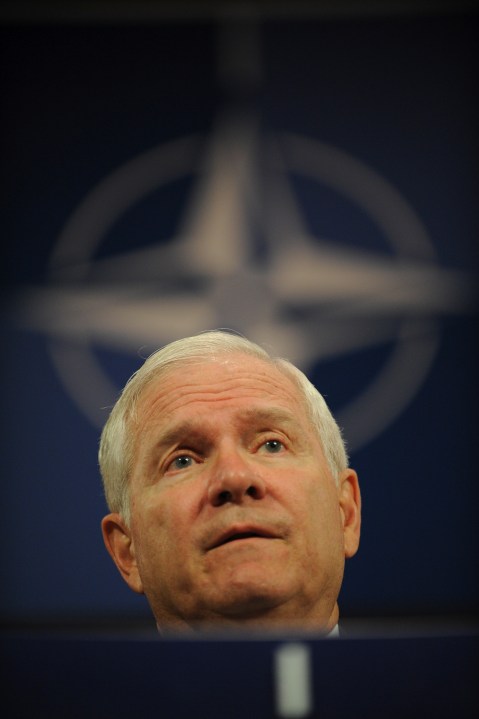

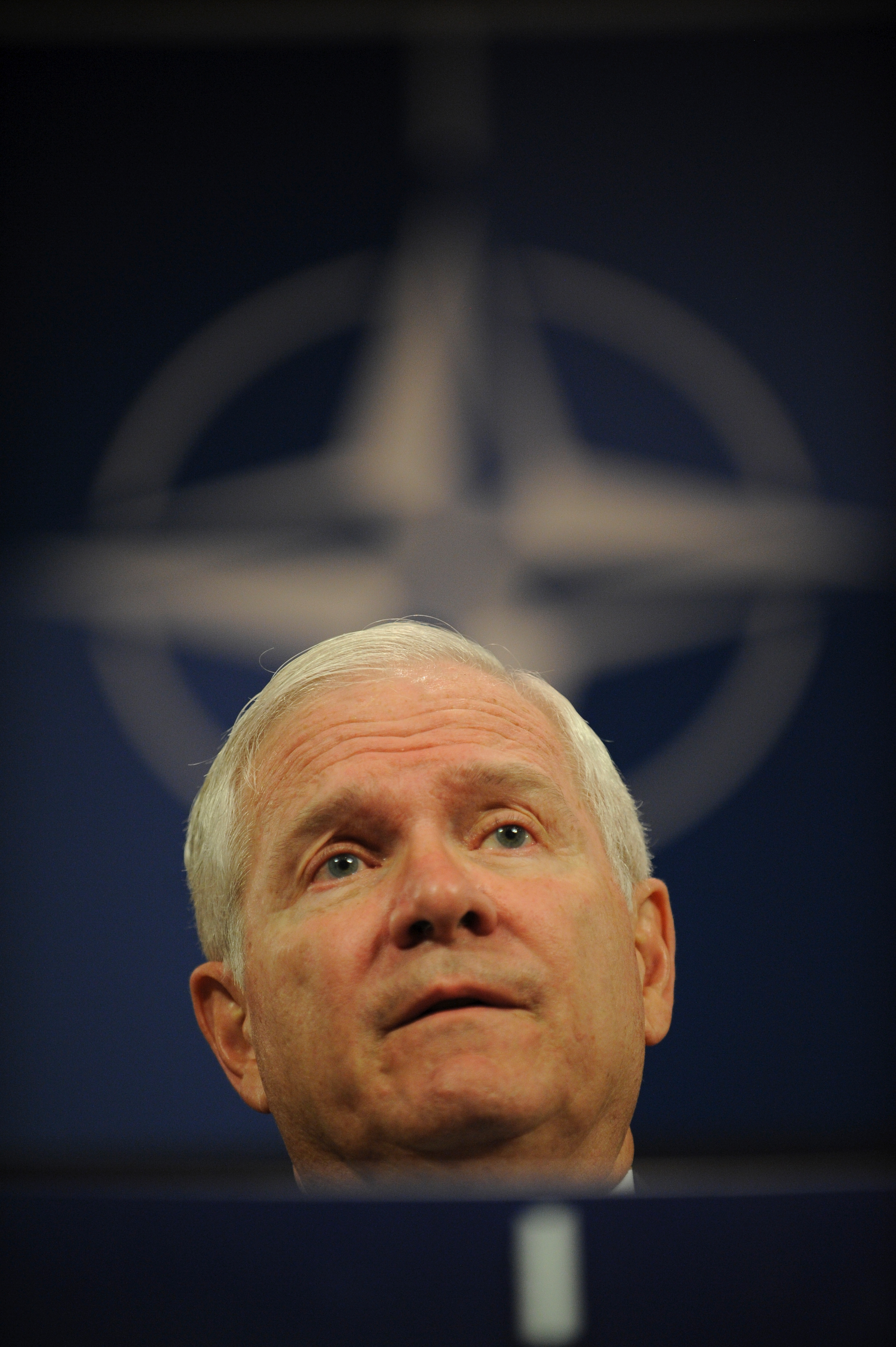

Robert Gates may be one of the best defence secretaries the United States has had in

modern times. But in slamming European allies, like he did in Brussels on Friday, he

was wrong.

Robert Gates may be one of the best defence secretaries the United States has had in

modern times. But in slamming European allies, like he did in Brussels on Friday, he

was wrong.

I have since long upbraided Europeans for under-investment in defence capabilities and making the wrong kind of investments. And defence expert Tomas Valasek published a fine pamphlet a few weeks ago, showing how European governments could do more for less, including by cooperating better. But they chose not to. This is not only foolish — as we live in an uncertain world where the ability to defend territory, trade, principles and people is paramount — but it also puts at risk Europe’s greatest defence mechanism: the goodwill and cooperation of the United States. With a pro-NATO generation of US foreign policy decision-makers retiring, the US has become at best a part-time European power. But it could go down to flexitime.

That said, Secretary Gates’ remarks last week were still ill-considered. First, nobody responds well to lecturing. Not the US government, not European governments. That is why Barack Obama has cultivated a different kind of language. Many European governments will also rightly feel upset about the Pentagon chief’s words, having responded to the Obama administration’s request to send more troops to Afghanistan. Today, many European states have a higher casualty rate per capita than the US. And few politicians in the UK and Denmark will find their jobs any easier after Gates’ comments.

Second, while I too fear US isolationism, let’s get real: you can’t threaten others to invest more in defence with the threat that if they don’t the US will turn inwards. The US will do what it finds in its own interest. If, in a world of rising autocratic states like China the US prefers to alienate its European allies it will soon find itself in an awkward position. For all their faults — and there are many — key European governments are still the best kind of all-weather friends the US will find.

Third, alliances like NATO work when there is either a shared sense of threat or sufficient solidarity to engage in burden-sharing. Many European governments do not feel threatened by Islamists in Pakistan and Afghanistan. In many respects, they are right. The risk of an al-Qaeda attack in Estonia is very low. Still, they have gone along with US-led operations like in Afghanistan. In turn, the US has been slow to appreciate their threats — like a restive Russia. Gates was said to be against the UK/French Libya operation — hardly a good position from which to criticise Europeans.

Finally, European governments, led by the UK, are dealing with their greatest security threat they face — the risk of economic collapse. To address it requires serious deficit-cutting. The US may believe that defence budget can be exempt but European governments thankfully don’t. That does not mean they should slash and burn at will. There are many ways in which they can make smarter defence investments in a budget-cutting era. But to exempt defence entirely is absurd.

Defence Secretary Gates has reminded Europeans that the alliance with the US cannot be free. But the manner of his intervention and some of the logic underlying it were flawed.

Comments