Adrian Heath (1920—92), like so many artists, was a mass of contradictions. Jane Rye begins her excellent study of him by quoting Elizabeth Bishop: ‘A life’s work is summed up as the dialectic of captivity and freedom, of fixed form and poetic extravagance, of social norms and personal deviance.’ Heath thought of his painting as an attempt to reconcile the intellectual and the sensual, a meeting point of classical and romantic. Roger Hilton complained that Heath couldn’t decide whether he wanted to be a painter or an accountant. Certainly, Heath did not conform to the public’s cherished image of the artist as bohemian. He wore a suit to visit galleries, came from a long line of soldiers and colonial administrators, had been educated at Bryanston and enjoyed private means. Some called him a ‘gentleman abstractionist’, yet few possessed his scholarship and intelligence or were anything like as devoted to a radical notion of the avant-garde.

Born in Burma, Heath was an only child and was soon sent back to England where he was brought up by women. Good at games, he was weak at maths and failed the entrance exam for the Royal Navy. Drawn to art, he admired flamboyant stylists such as Sargent and wanted to be a portrait painter. In 1939 he worked with Stanhope Forbes in Newlyn, fell in love for the first time, and studied briefly at the Slade before joining the RAF. After his plane crashed on active service, he became a PoW and continued to paint in captivity, inspiring a number of fellow prisoners, including Terry Frost. But Heath was not content to sit back and paint. He escaped from camp four times, and spent a year in solitary confinement, during which time he said he started seriously thinking about abstract shapes, by rearranging in his mind’s eye the cracks in the wall.

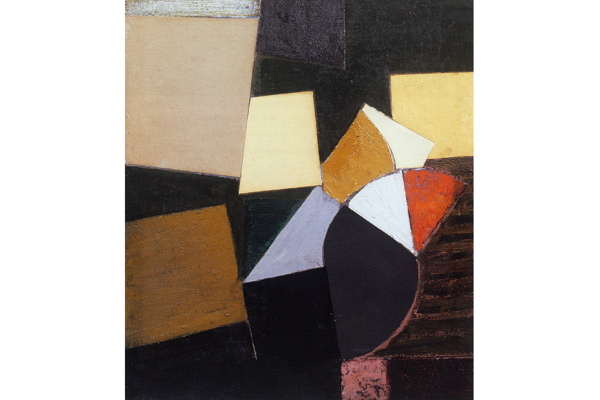

On his release, one of the first things he did was to walk down Bond Street and buy some art: drawings by Sickert, Meninsky and Wyndham Lewis, and a small painting by Victor Pasmore. Pasmore became his mentor and friend, and it was under his tutelage that Heath emerged from the Camberwell/Euston Road tradition of realist painting into the wider waters of non-objective abstraction. The 1950s was undoubtedly his greatest period, and this book is arranged in three parts, with the central section being devoted to these years. This was when he made his purest abstract paintings, mostly in a restricted palette of browns, greys, blacks and ochres. (He had a provocative theory that anyone who wanted to be surrounded by strong colour was probably undersexed.)

The contradictions at the heart of Heath continued. He was a family man yet serially unfaithful. (One source said he was ‘a bomb in bed’.) This is relevant, because so much of his later work was erotic and fleshly in content, and consequently more painterly and spontaneous in style. ‘He was a man of remarkable energy,’ writes Rye, ‘small and tough, with a boyish mop of hair over one eye and a mischievous expression; amusing, caustic, a natural leader; insouciant, likeable, with a tact that made him a useful committee man. . . .’ He was also refreshingly against self-expression, and used the structures of abstraction to inhibit it.

Rye offers us an elegantly composed account of the man and his period, but I would have liked a little more comparison and cross-referencing with such contemporaries as Peter Lanyon and William Gear, both of whom shared similar preoccupations. Her prose is limpid and her clarity of approach a sharp delight in a world dominated by semi-literate persiflage and the one-upmanship theorising of academic art historians. On the evidence of this eminently readable book, Adrian Heath is a much more interesting artist than I had previously realised. It is time to look again at his paintings and drawings.

Comments