The Budget contained little economic analysis of George Osborne’s sensational plan for a £9 minimum wage for the over-25s. Of course, it’s not driven by economics: the main objective is to destabilise the Labour Party. So far, the policy is being defended by Tories using rather flimsy logic: business moaned when Tony Blair introduced the minimum wage, but did that create mass unemployment? Eh, no. So we can ignore those who moan now; they’ll come around.

But, alas, things are a little more complicated than that.

The OBR has already broken the news the Living Wage helps richest households almost twice as much as poorer ones, because so many minimum wage workers are the spouses of high earners. Yes, all of this discomfits Labour. Yes, it provides political cover for Osborne as he cuts tax credits. But let’s not pretend that the Living Wage is a great progressive reform.

But no one has really asked how much of the workforce will, under Osborne’s new plan, have their wages set by the government. In 1997, the National Minimum Wage covered just 3pc of workers. Now look at the below chart (from Citi) showing pay for over-21s. Osborne’s so-called ‘Living Wage’ applies to over-25s so the figures won’t be the same, but they will be close.

So as of next April, when the £7.20ph wage comes in (blue dotted line), the UK government will be setting the wages for about 10pc of men and 18pc of women: quite a power grab. But that’s just the start. A £9 minimum wage in 2020 means about £8 today, so that’s closer to 20pc of all employees (and over a quarter of women, who make up most NMW empoyees). It won’t be quite so high because average salaries will have risen a fair bit for everyone (hopefully).

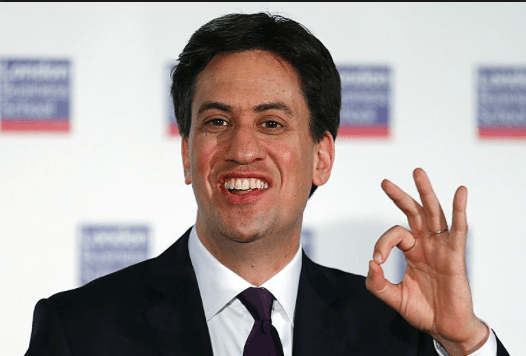

Now, is it right that the UK government should control the pay and conditions of so many workers? George Osborne and Ed Miliband both think so, but only Miliband made his case during the general election campaign. We’re still not quite sure about the rationale for Osborne’s change of heart. A compulsory Living Wage was considered, and rejected, by those drafting the Tory manifesto so already the Tory Party we’re getting is, in several important regards, fundamentally different to the one that asked for a mandate a few weeks back. It now agrees with Ed Miliband in the need for significantly more government intervention in the setting of wages.

The question of a minimum wage stirs such passion because it addresses a fundamental question: how far should the government set wages in a free society? In the Thatcher era, the Tories had a simple answer: not at all. Then Tony Blair made and won the argument for a national minimum wage. It was set by a Low Pay Commission that was evidence-based and keen to minimise the number of joblessness.

Blair wanted to ensure that hard-nosed economic evidence – rather than vote-hungry politicians – would decide the minimum wage. That’s why Labour never issued edicts to the Low Pay Commission. As the FT’s Sarah O’Connor says, the Low Pay Commission…

…is seen internationally as one of Britain’s policy success stories: its nine commissioners, a mixture of independent experts and representatives from both trade unions and employers. It has raised the minimum wage steadily without hurting employment levels, although some have criticised it for being too timid.

Miliband certainly thought the Low Pay Commission too timid: if elected, he told us that he’d issue it with marching orders– and to blazes with its calculations about how to set the wage in a way that does not interfere with employment! Tories criticised this as being dirigiste. Just have a bit of faith, David Cameron argued at the time, the minimum wage will probably head north of £8/hr anyway by 2020. So why legislate? Look around, look at the emerging labour shortages, look at the record numbers of employers reporting difficulty finding staff! This is a prelude to wage rises, and no mistake. Already, pay rises are at an eight-year high.

Miliband’s £8/hr proposal was a hard example of his governing philosophy: that the market could not be trusted with the recovery. Cameron’s mockery of Miliband’s £8 pledge was also a hard example of his (now-defunct) liberal approach to economic management. This distinction has now vanished.

Yes, Miliband failed to win the election. But he gave the Tories the fright of their life during the election campaign, and seems to have converted them into the wisdom of far greater state interventions in the setting of salaries.

Now this may well be, as Nick Clegg said today, an act of tactical genius on Osborne’s part. But credit where it’s due. Politics is about ideas as well as power. Those of us who derided Miliband for so many years really ought to accept that he has, on this totemic issue, won the Tories over on a very important argument.

Comments