While Britain bakes in a heatwave, politicians in Germany are worrying about the winter. The Russian state-owned gas company Gazprom has notified its European customers that it can no longer guarantee the supply of fuel due to ‘extraordinary’ circumstances. In Berlin, politicians and regulators are preparing for an ice-cold Christmas, drawing up lists for rationing priorities and emergency plans to stop the population freezing.

Entertainment and frivolities will be the first things to go, while newspapers and medical production will be prioritised alongside households and hospitals. Mothballed coal power plants are being prepared for reactivation. Some local governments are planning to turn public buildings into ‘warming halls’ for those unable to heat their homes or turn off traffic lights, setting up ‘industrial-scale dormitories’.

The most heated debate is whether the government should prioritise residential consumption over the economy. While current plans aim to sacrifice economic output in favour of keeping homes warm, industry groups are pushing back, claiming a shutdown would be the ‘worst crisis since the second world war’. The charity Caritas has also come out against the plans, warning that gas is needed ‘to produce basic foodstuffs like milk and essential medicines’, and ‘blood reserves for the gravely injured’. One set of estimates reckoned a full shutdown would cost Germany 2 per cent of GDP and 400,000 jobs; another put the cost closer to 12 per cent of output.

Take a step back and appreciate the insanity of these paragraphs. A 21st century European country is warning households to prepare for rolling power cuts as the state attempts to keep the economy functioning without fuel. Housing associations are already rationing hot water and heating as prices rise; a full shut-down would be exponentially worse.

One set of estimates reckoned a full shutdown would cost Germany 2 per cent of GDP and 400,000 jobs

The Nord Stream 1 pipeline carrying gas from Russia to Germany is currently down for scheduled maintenance, with supplies scheduled to resume on Thursday. The concern in European capitals is that the tap won’t be turned back on. Prior to the shutdown, Gazprom had already cut flows significantly, claiming that the absence of a replacement turbine – held up by sanctions – was to blame. German sources rejected this claim, pointing out that the new part wasn’t intended for use until September. Instead, the disruption looks like a reminder: push us too far, and we will turn off the taps.

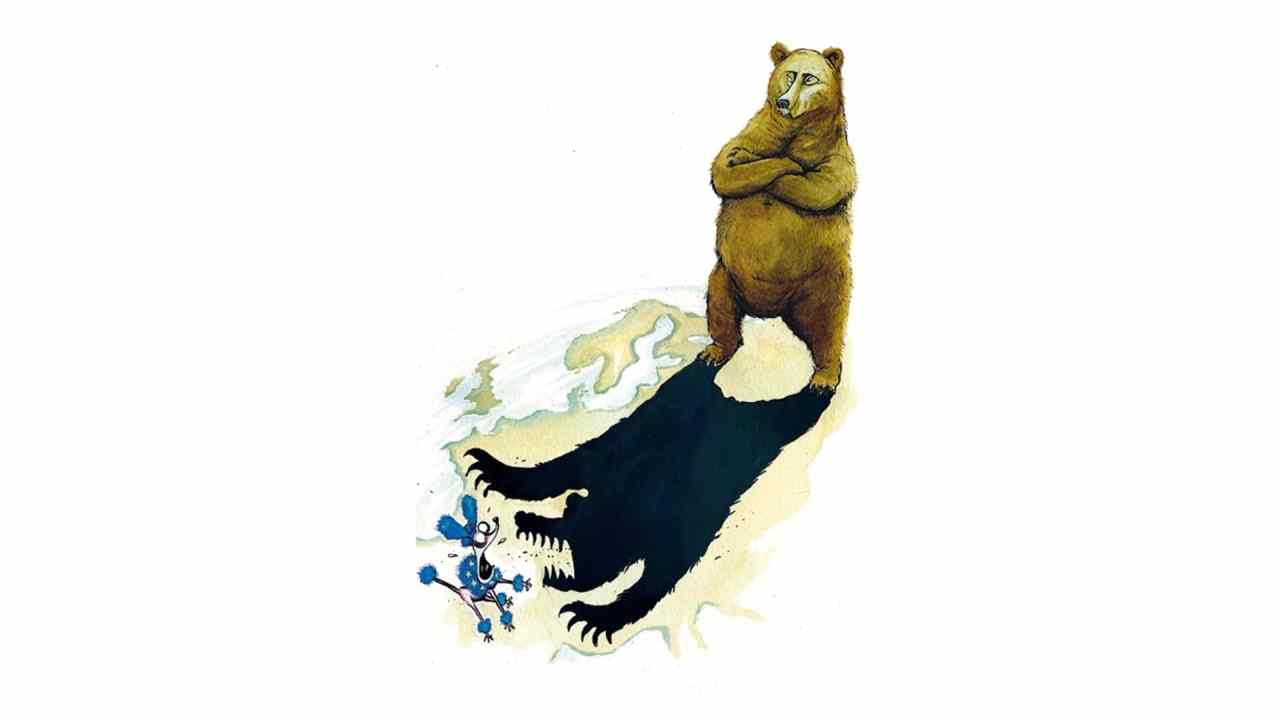

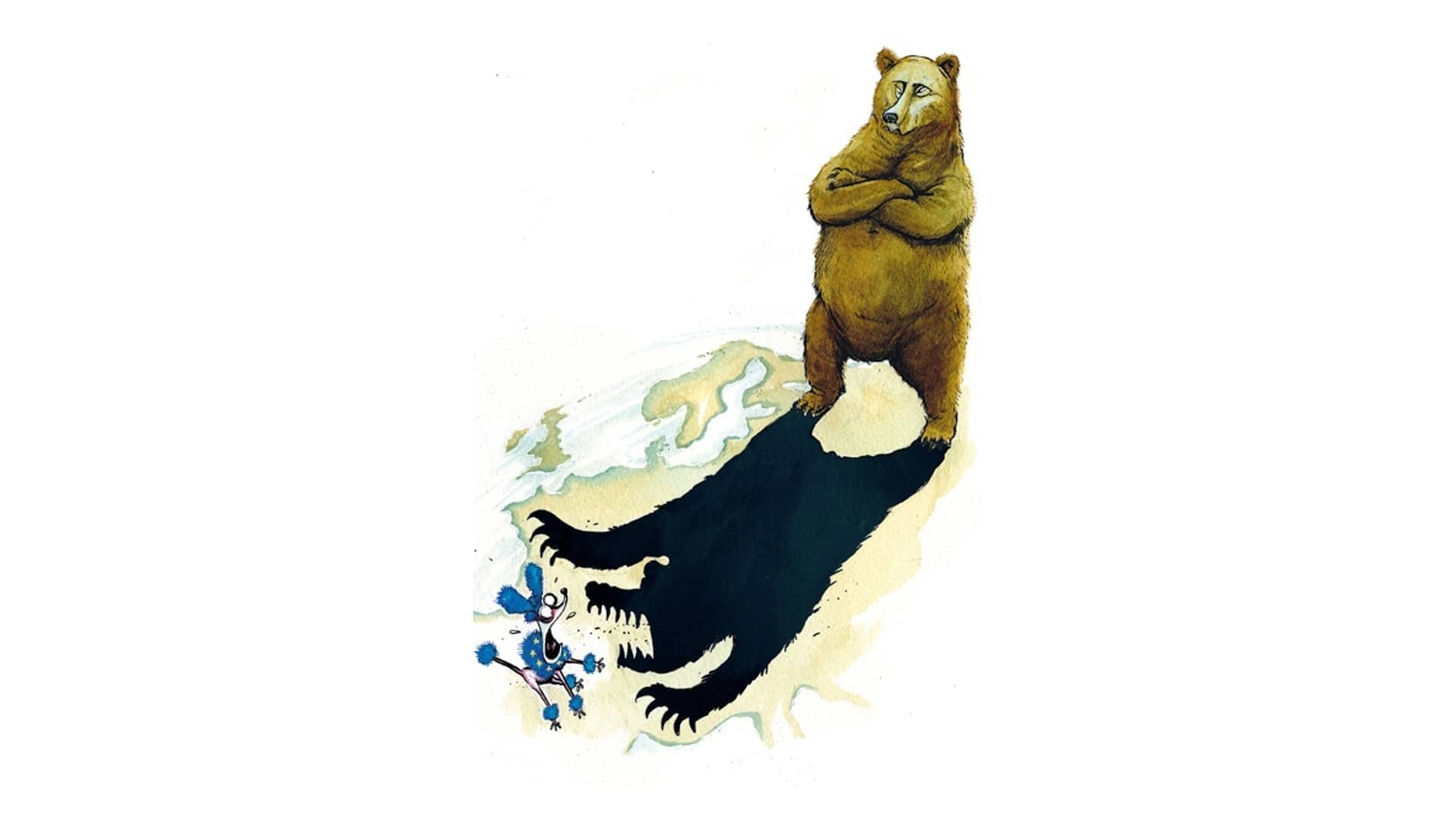

While the Pentagon pours money into developing directed energy weapons, Moscow has already developed a potent energy weapon of its own. Russia prepared for the war in Ukraine by slowly lowering supplies to Europe, making sure the continent entered 2022 with storage levels at a ten year low– barely sufficient to make it through to summer.

While this didn’t keep the West out of Ukraine entirely, it did punch a hole in the sanctions regime as gas and hard currency continued to flow back and forth between Russia and Europe. Moscow’s reluctance to end this exchange is understandable; while Europe relies on Russia for fuel, Russia relies on its fuel for foreign exchange, and its pipelines are built to channel gas to Europe.

But with rising inflation already causing disquiet in the West, reserves low, and winter looming, the current situation might just give Putin enough leverage to make the hit of a shutdown worth it. The interests of Ukraine and its western sponsors have never been totally aligned; Kiev is fighting for territorial integrity, while its allies spot an opportunity to bleed out Russian strength. These causes imply that the two will have a fundamental difference in the willingness to bear pain in the conflict.

What is existential for Ukraine is not so for its European allies, who may start to pressure Kiev into accepting a ceasefire. While some worry this could embolden Russia to rearm, rebuild, and eventually restart conflict – in Ukraine or elsewhere – there is also a point of view that you can only bear so much pain to prevent conflicts which don’t involve Nato or EU countries. Threatening to withhold gas supplies pushes at these cracks in the western alliance.

And Germany, which sources somewhere between 50 and 70 per cent of its gas consumption from Russia, looks like the weak link. It’s looked this way for a long time; Donald Trump warned Berlin that it would ‘become totally dependent on Russian energy’. Left wing news sites set his speech to jaunty music, interspersed with clips of Germany’s UN delegation laughing at his ignorance.

It’s safe to say they aren’t laughing now. From shutting down nuclear plants to pushing ahead with Nord Stream 2, to simply ignoring warnings in 2014 that its existing relationship with Moscow had undermined Europe’s ability to respond to Russian military aggression, it’s difficult to think of a way Germany could have made itself more dependent on Russian goodwill if it had tried.

The German economy minister, Robert Habeck, is quoted as saying he ‘would be lying if I said I was not afraid’ of a halt in supplies. If Putin carries through with his threat, it will be interesting to see how long German resolve lasts through a winter without fuel.

Comments