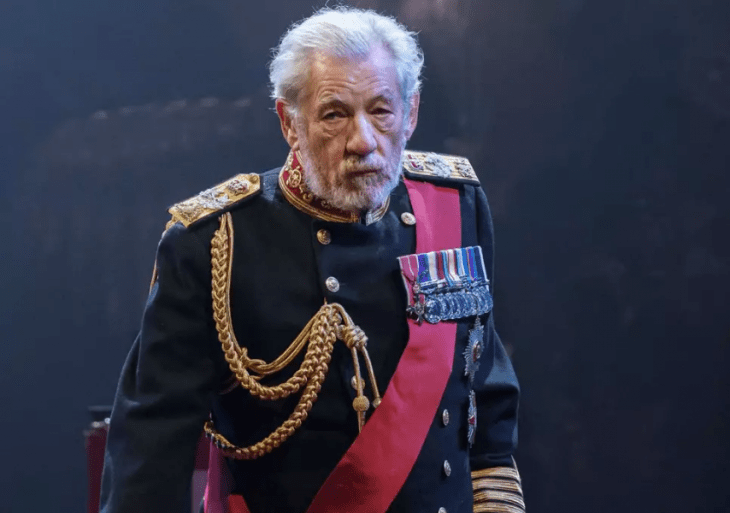

Gandalf, also known as Ian McKellen, has awarded himself another lap of honour by bringing King Lear back to London. Jonathan Munby directs. His eccentric decision to hire actors who don’t resemble their characters will baffle anyone who hasn’t studied the play in advance. The casting may be ‘colour-blind’, but the audience isn’t. Anita-Joy Uwajeh (Cordelia) evidently has no white ancestry and therefore cannot be Lear’s natural daughter. A newcomer might deduce that the king’s cruelty towards her stems from her second-class status as an adoptive child. And anyone trying to unravel that mystery will be equally baffled by Sinead Cusack’s Kent. Of the four women on stage in the opening scene, three are members of Lear’s family so it would be reasonable to assume that the fourth, Ms Cusack, is also a relative. Is she Lear’s sister, his cousin, an aunt perhaps, or his wife? Even I found her role hard to decipher and I’ve sat through this problematic play a dozen times or more.

The difficulty arises from the main character and his shattered personality which appears in the following manifestations: self-pitying despot, irascible scrounger, ranting visionary, chastened penitent. None of these is particularly sympathetic and the characters around him are, with the odd exception, a loathsome bunch of schemers and killers. The artistic texture of the play is unendurably harsh and alienating. Long screeds of barmy rhetoric are interrupted by scenes of bullying, torture, poisoning and summary execution. The first half, which lasts two hours in this production, moves sluggishly and the second half seems rushed and overcrammed with sudden plot twists. Amid the dross, the odd gem shines. ‘Thou rascal beadle, hold thy bloody hand [etc]’ says Lear, denouncing the perverted lust of magistrates who enjoy flogging prostitutes.

The show has a few virtues (or pain-free moments to label them more accurately). Early on, Lear uses a pair of comedy scissors to slice a map of his realm into three. That’s funny. The storm scene has a muted sound-track which allows McKellen’s shrieks to be heard without placing that fruity old voice-box in danger. The Fool is performed by a banjo-playing Ulsterman who impersonates McKellen in a way that seems both hilarious and enjoyably disrespectful. The final tableau, in which Lear cradles Cordelia’s corpse, is often considered by viewers to be ‘unbearably moving’. Not by this viewer. The stupid old tosser got what he deserved. At press night, the stoical crowd endured Gandalf’s pet project with admirable patience. Scarcely a cough or throat-clearance throughout. Sir Ian has now inflicted this horror show twice on his loyal public. Can we offer him a peerage if he promises not to reoffend?

Eugene Ionesco admired the notion that everything wrought by kings and politicians is worthless. Why he didn’t apply the same stricture to absurdist playwrights isn’t clear. Exit the King, in a beautiful production by Patrick Marber, demonstrates his failings as a dramatist. He can’t tell stories or develop characters. And instead of a plot, he invents a predicament. A sick king living in a broken palace at the centre of a crumbling realm must face his mortality. ‘You die at the end of the play,’ his first wife tells him. The stricken monarch moves from anger, to despair and finally to acceptance with the help of his two consorts (one wise, one foolish, both unchanging), and a handful of clowning attendants. The script is motionless.

To spice things up, Ionesco inflicts fresh cataclysms on the already-doomed empire and reveals new information about the king, who turns out to be a wizard with magical powers who has been alive for over four centuries. The show is superficial, easy to watch, and wrongly convinced of its own significance. Ionesco was a great admirer of Hamlet’s metaphysical utterances and he felt that Shakespeare could do with some competition. ‘Why was I born if not for infinity?’ asks the king. It’s a half-decent gag and it gets a half-decent laugh. ‘I stand on the edge of myself,’ he mourns. ‘I look inside my myself. And I see darkness.’ Nicely phrased but banal. Rather like the show which is just an overblown pantomime for pipe-and-stubble existentialists.

Louche, camp, and brimful of mischief, Rhys Ifans plays the king as an adorable rascal. If Peter O’Toole were a young actor today we would call him the new Rhys Ifans. He’s a star. At the close, the palace breaks apart and the king’s narrow strip of red carpet turns into a scarlet avenue suspended in a womb-black darkness that leads to infinity. An astonishing visual effect. Years will pass before anything as beautiful as this is seen at the Olivier. Unfortunately the script requires the actors to babble and yacket for ten minutes while the king shuffles up the red lane towards heaven. A shame. That spectacular closing image deserved silence.

Comments