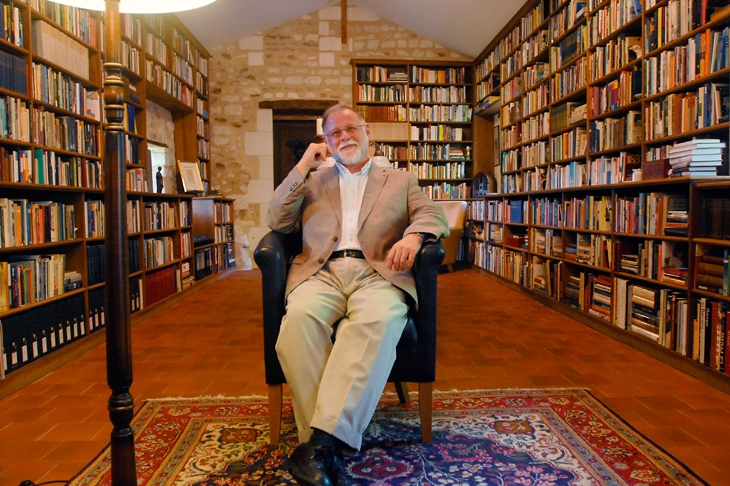

Alberto Manguel is a kind of global Reader Laureate: he is reading’s champion, its keenest student and most zealous proselytiser, an ideal exemplar of the Reader embodied. And reading is not only his committed, devoted practice, but also the very subject of some of his best writing. His latest book to wander through this familiar domain was prompted by the traumatic experience of packing away his huge personal library, when he and his partner found themselves needing to downsize from a cavernous French barn (containing 35,000 volumes ‘in its prime’) to a small apartment in New York City.

Packing My Library: An Elegy and Ten Digressions is a loosely arranged collection of small essays triggered by this change in his relationship to his books, and — because a library is always a manifestation of autobiography — a necessary reappraisal of where this change will leave him. This is a man whose life experiences have always been given meaning by his reading experiences: when a white owl flies past, it’s not just a white owl, but ‘like the angel that Dante describes steering the ship of souls to the shores of Purgatory’.

As ever, Manguel ranges widely. The serendipitous pleasures of dictionaries, the mysteries of books’ true origins, remembering and forgetting, the popular trope of the writer starving in an unheated garret, how language embodies faith, the Golem, the inevitable failure of any author’s attempt to represent reality perfectly (unless that author is God), the inevitability of human aloneness — all these and more have a place in this small, generous book. Opening it at random on page 88, I find Stephen Hawking, Humpty Dumpty and Nebuchadnezzar. As when browsing a library, there’s seeming randomness in the order — or is it the other way around? — and it isn’t always easy to keep up (clever writing insists upon clever reading, after all); but the erudite mixes nicely with the personal, too. One sentence begins: ‘Plato, who would have agreed with my grandmother….’

Manguel’s own libraries (plural) began in childhood, with that first shelf of bedtime stories in his toddler years. His relationship to books has always been a physical relationship (he recognises the convenience of modern ‘immaterial books’, but feels ‘you cannot truly possess a ghost’), and one dependent on personal ownership, on having them always immediately to hand, being able to annotate them at will. These physical objects are rich in association — where they were read, from whom they were received, what this particular edition looks like. The physical particularity matters to him. He is a generous giver of books to his friends — just don’t ask to borrow one of his.

This self-portrait of the reader as devoted book-owner makes it easy to understand, then, how painful it was to have this part of himself wrenched away. ‘I’ve often felt that my library explained who I was,’ he writes, which makes packing it up ‘something of a self-obituary.’ Will he, like Don Quixote, manage to draw strength from his remembered library even when the real thing has been torn from him?

Just as a private library reveals its owner, so a civic one should be a shared cartography expressing ‘a projected communal identity’. Manguel’s early emphasis on private ownership rather than communal ownership lays the ground for the book’s closing movement, in which he finds himself appointed director of Argentina’s National Library, in the distinctly bookish city of Buenos Aires — a city ‘founded with a library’, he says proudly. Former holders of this post included Jorge Luís Borges, to whom the schoolboy Manguel used to read. Borges — one of no fewer than four blind directors of that library — took the opposing view on book ownership to Manguel’s, and had no significant library of his own.

Early in Packing My Library, Manguel acknowledges his digressive tendencies, all the better to embrace them; and at the end he accepts that, yes, this curious little book has been somewhat disjointed. But it doesn’t much matter. Because while it’s reflective, even celebratory, what it isn’t doing is making an argument, convincing those who don’t already recognise their passions reflected in his.

Instead, as the epigraph from Cicero suggests, it’s not about persuading others of ‘the beauties of the universe’, but about sharing them; if you value these particular pleasures already, you may find yourself the ideal reader for Alberto Manguel.

Comments