In late April 1992, I was in Crete, interviewing the painter John Craxton. It was the week that Francis Bacon died. We heard the news on the BBC World service, and afterwards Craxton reminisced about his old friend. Craxton himself at that stage had almost disappeared into obscurity. He was living in a elegantly crumbly building overlooking the harbour at Chania. It wasn’t grand, but there was a small Matisse cut-out hanging on his sitting-room wall.

In recent years Craxton has been undergoing a minor revival. There has been a book, a show at the Fitzwilliam; now this sizable exhibition — Charmed lives in Greece — devoted to him, together with the Greek painter Niko Ghika (Nikos Hadjikyriakos-Ghikas, 1906–1994), and the writer Patrick Leigh Fermor.

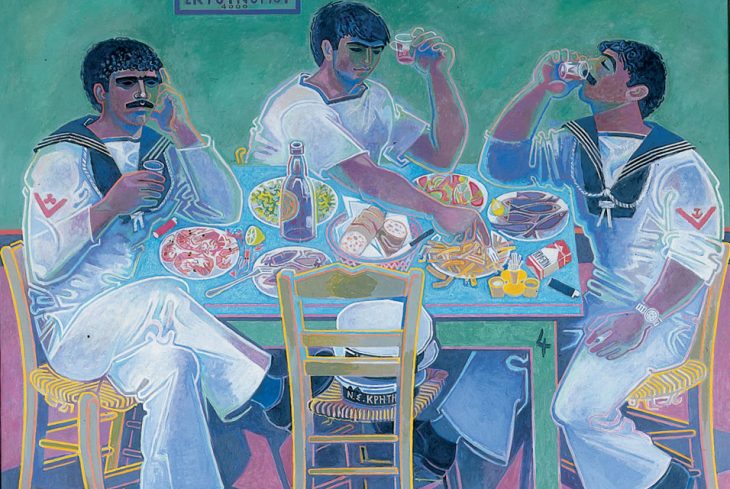

The works on show do indeed have a lot of charm, as Craxton did himself, but the title raises another question. Was his life charmed in another sense? He lived in Greece on and off for decades, and settled more or less permanently in Crete in 1970. In the book accompanying the exhibition, Craxton’s biographer, Ian Collins, notes that in his later years a large black canvas generally sat on his easel, ‘apparently as a deterrence to further labour’. Had Craxton wandered into the land of the Lotus-eaters, which the sailors in The Odyssey found ‘was so delicious that those who ate of it left off caring about home’?

During the war — a period not covered by this exhibition — Craxton (1922–2009), was one of the most successful of the group of artists dubbed ‘neo-romantic’, a term he detested. At 19 he was sharing a house with the equally youthful Lucian Freud, each of them working on a different floor. He must then have seemed one of the coming forces in British painting.

Craxton’s arrival in Greece brings to mind the plot of a film by Powell and Pressburger — and also Leigh Fermor’s romantically picaresque travels. In 1946 Craxton found himself in Switzerland and was, he told me, ‘about to be shot by the husband of the woman I was staying with because he thought we were having an affair’. (Craxton was bisexual.) At this point, he met the wife of the British ambassador to Athens in a bar. She said he must come with her to Greece; Craxton’s hostess enthusiastically supported the idea. ‘So we set off in a bomber from Milan.’

For a while he lived in the embassy garage. But Clifford Norton, the ambassador, found him ‘too Bohemian a guest’. So, on the advice of Leigh Fermor — a new friend — he went to live on the island of Poros. ‘It was like striking oil that first summer,’ he remembered, ‘Greece was lovely then, it was a marvellous moment.’ And indeed, those very first pictures were some of the best he did in Greece.

It must have seemed a wonderful escape from postwar Britain.

But there was an art historical logic to Craxton’s move. Like most British artists of the mid-20th century, he was in awe of Picasso. In Byzantine art he found an analogy to cubism; indeed one of cubism’s roots was Byzantine since Picasso himself had been deeply affected by the Cretan artist El Greco.

This connection makes the fractured planes of Craxton’s Greek landscapes seem new and old at the same time. You could say of them what he noted about Byzantine paintings. ‘The rocks are abstracted, but they manage to impose in that abstracted shape the feeling of rock — the essence of rock.’

Much the same is true of Ghika, an artist not much known in this country. In his youth Ghika had studied Byzantine art as well as the art of the Parisian avant-garde. A picture such as ‘Wild Garden’ (1959) blends all of those ingredients: jagged geometry, Matisse-like foliage, and a feeling of the Eastern Mediterranean. Ghika’s pictures sometimes upstage Craxton’s at the BM; it looks as if the older Greek artist influenced the younger English one.

Another artist was briefly part of this tiny Anglo-Hellenic community. Lucian Freud joined Craxton on Poros in 1946, producing some lovely paintings (some of which would have added another dimension to this exhibition). But later they fell out spectacularly and their later careers, and work, could scarcely have been more different.

Freud once professed ‘a horror of the idyllic’, whereas Craxton was described as ‘a self-confessed Arcadian’ (although when I put it to him, he rejected the word indignantly: ‘I never confessed I was an Arcadian!’). But he was a romantic. Many of the exhibits are beguiling, not least Craxton’s covers for Leigh Fermor’s books (the writer is otherwise represented mainly by photographs and documentary material).

There is a gentle softness about Craxton’s work: too much charm, not enough truth. The paintings of people — generally young men — have a slightly soppy air. But landscapes such as ‘Cretan Gorge’ (early 70s), halfway between geometric abstraction and the spiky terrain of a medieval Greek icon, are tougher and more impressive. He deserves another look.

Comments