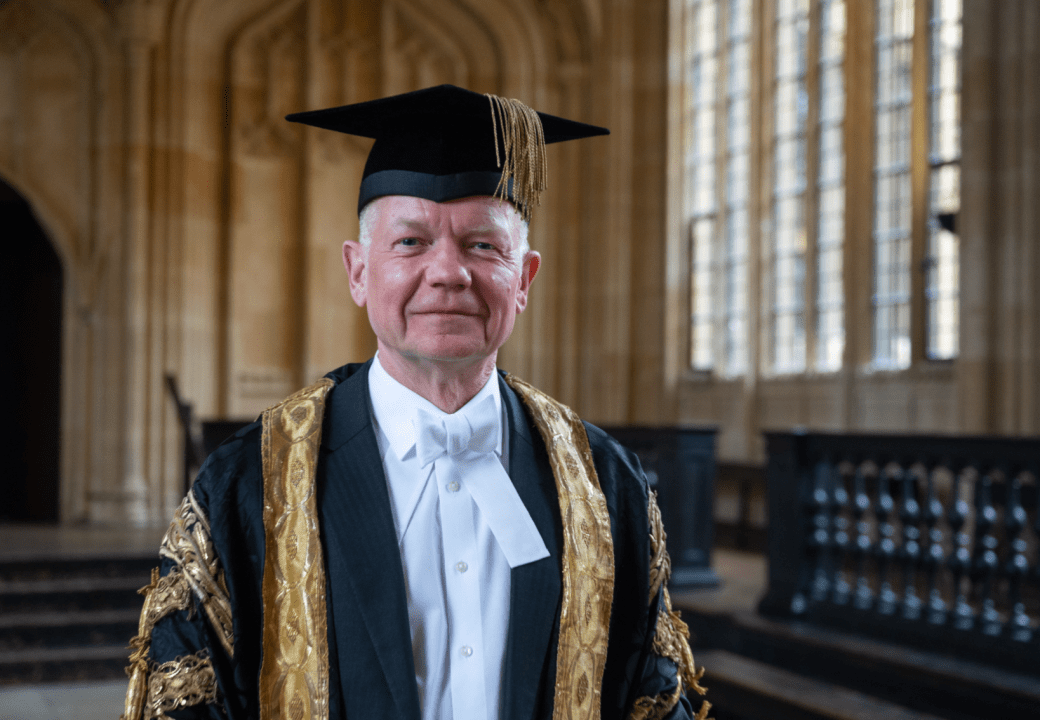

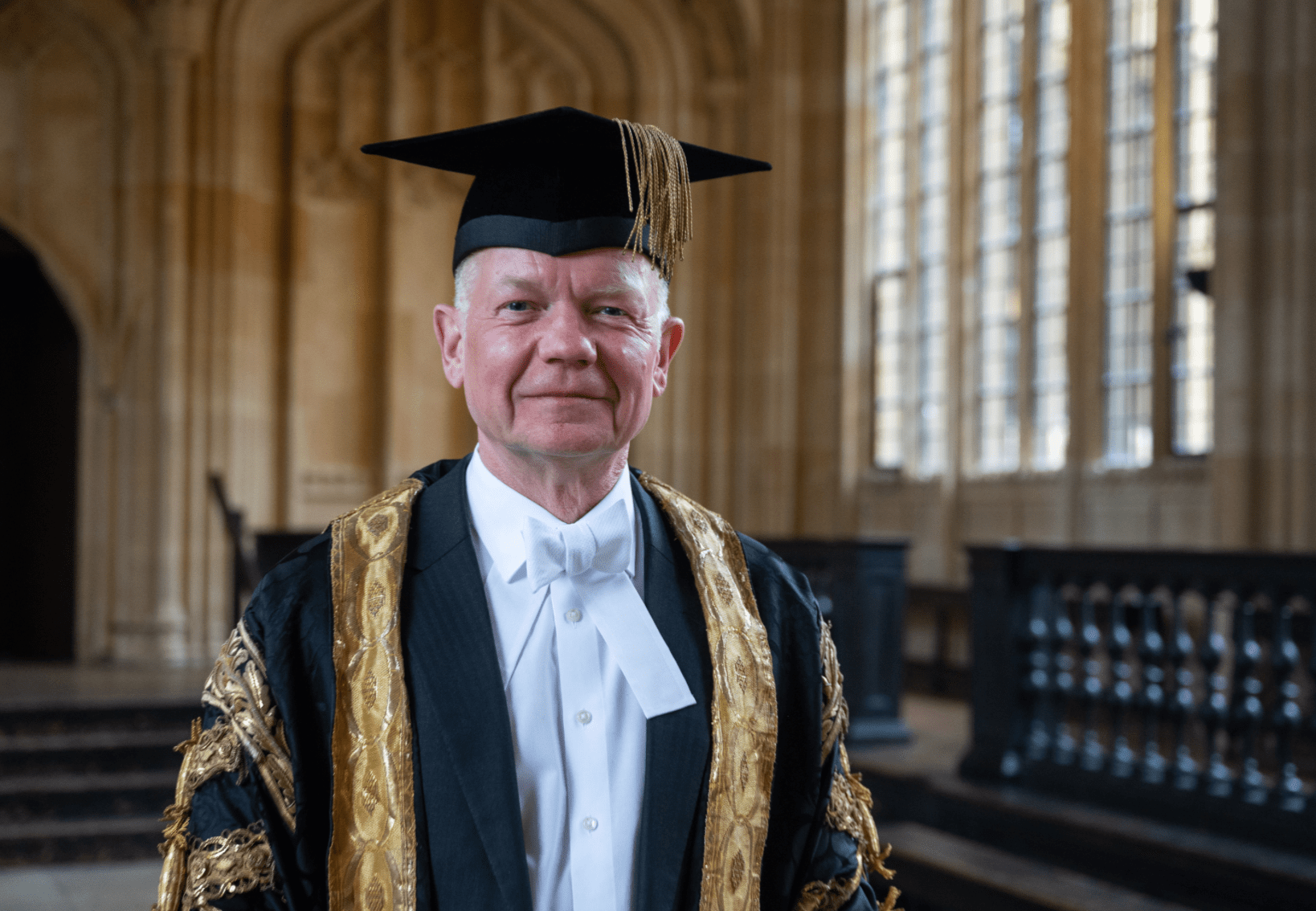

To Oxford, where William Hague was today admitted as the university’s 160th chancellor. In an hour-long ceremony, the onetime Tory leader was welcomed by Jonathan Katz, Oxford’s Public Orator. He reflected on Chris Patten’s decision to retire as Chancellor, noting that ‘there are precedents’ – indeed, to use ‘academic terminology’, ‘the great Creator himself took a sabbatical – the first, indeed, after a busy week one of his term.’

Reflecting on how political office had prepared Hague, Katz wondered whether he would find the role to be more of a ‘poisoned chalice’ or a ‘holy grail’ – ‘I predict more confidently that many will be those among us who wish to offer you the best of what they have, correctly passed, naturally, in the right direction around the table.’ He suggested too that Hague would be well-placed to pontificate on how Oxford now differs since his days as an undergraduate in the 1970s – ‘You will be the best judge, but we do not expect to hear you assert that NOTHING HAS CHANGED.’ Sadly, Theresa May wasn’t in the audience to appreciate the line – though Alan Duncan certainly did.

Katz next moved on to Hague’s own academic studies, confessing he thought the new Chancellor had been a history undergraduate at Oxford. ‘This was, I plead, an understandable misapprehension; you have, after all, written highly commended history books, though their very readability should have been enough to suggest that you were not adversely influenced by the profession.’ The attendant historians particularly enjoyed the line.

Then it was the turn of the former Union president. Hague began by noting the welcome presence of his predecessor, Lord Patten. ‘It is a wonderful event that we have a Chancellor Emeritus here. The last chancellor to relinquish the role in their lifetime, the second Duke of Ormonde in 1715, fled the country immediately – I am very pleased that Chris has seen no need to do so.’ Hague added that he had not just known his immediate predecessor – but the two before him as well:

Harold Macmillan was ninety when I, in my twenties, eagerly told him of my plans to enter parliament and ambitiously asked for his advice on running the country once I got there. There was a long pause as he took me in, with the penetrating gaze of those hooded eyes. ‘Young man’, he said, ‘don’t do too much, too soon’. That was it – useless, I thought. But ten years later when I had rashly allowed myself to be elected leader of my party, I realised how very shrewd that advice had been.

After Macmillan, came Roy Jenkins, Chancellor from 1987 to 2003. Upon hearing that Hague was about to start a book on Pitt the Younger, Jenkins immediately took him out to lunch and plied him with claret in a smart London club:

He asked me what word limit my publisher had given me. “150,000 words”, I said. “Well, the first thing you need to know”, he said, “is to take no notice of that whatsoever. If you are enjoying writing, the readers will enjoy reading it – you can add another 100,000 words and they’ll publish it anyway”. I did. And they did, which is why both of my books are much longer than anybody intended.

In reflecting on some of his other predecessors, Hague promised the assembled academics that ‘ you will find me less interfering than Lord Curzon, not so dogmatic as Oliver Cromwell, a touch less strict than the Duke of Wellington, hopefully more unifying than Cardinal Pole.’ He predicted that there would, inevitably, be some missteps and disagreements in the coming years, but that ‘with 56 departments, 43 colleges and halls, 43 institutes and 78 committees of the Council of the university alone we will make mistakes, but we will never all make the same mistake at the same time.’

Fingers crossed eh?

Comments