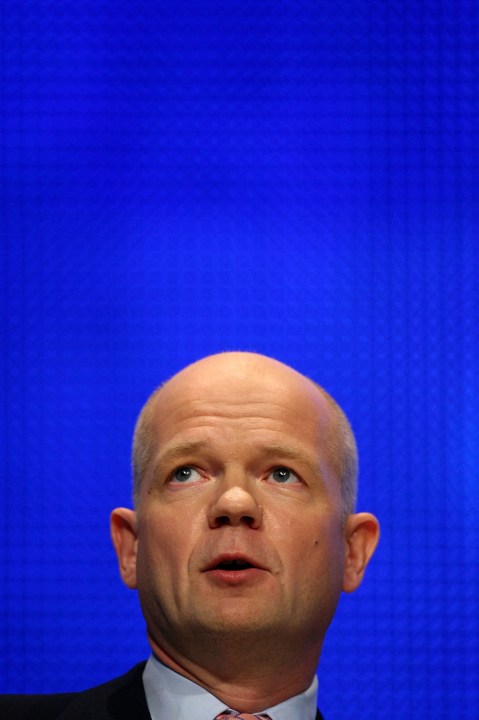

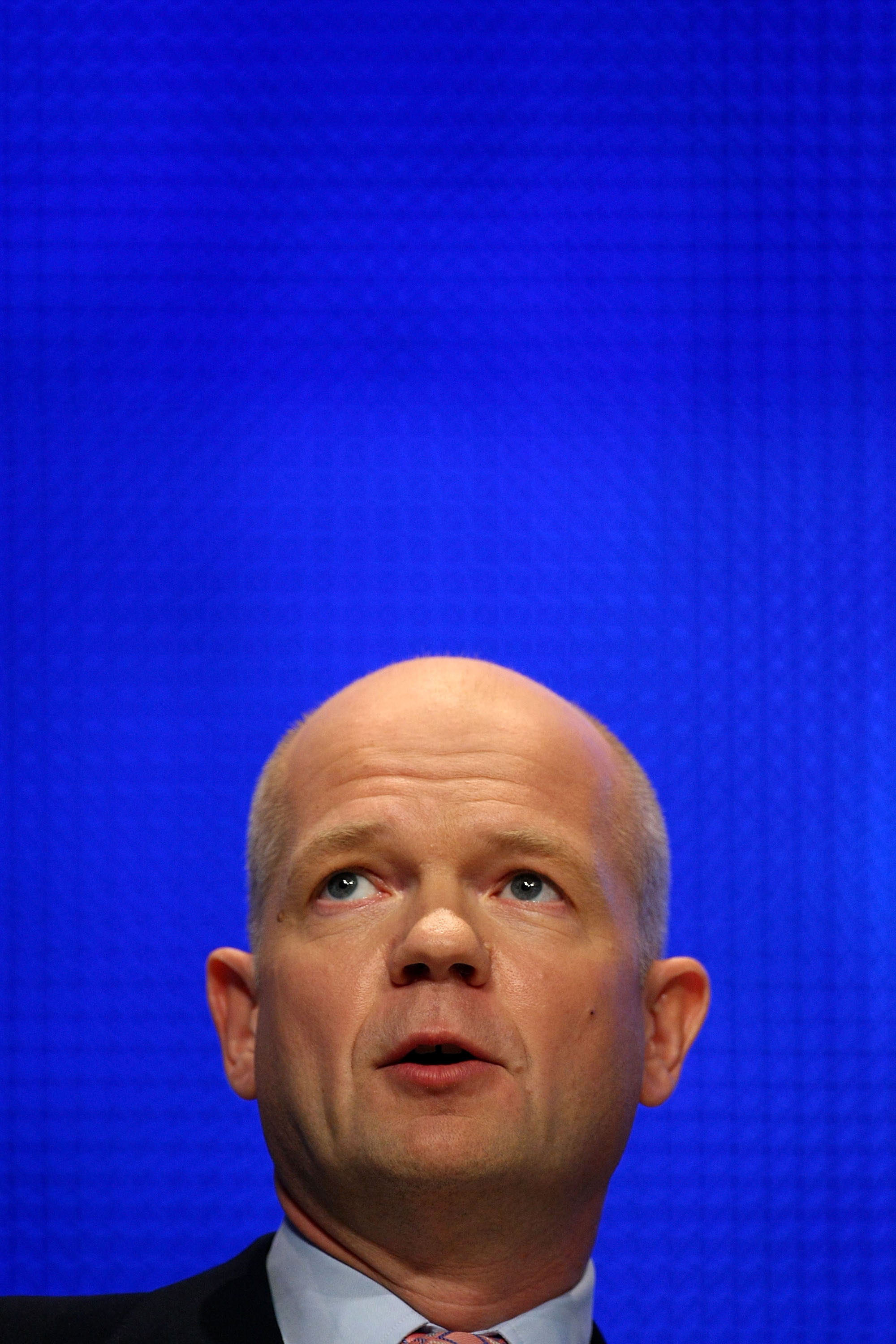

This week William Hague is visiting Bosnia, trying to highlight the problems in the country 13 years after the Bosnian War that saw 100, 000 civilian die. His visit provides welcome attention to the country’s slide towards conflict; while he can helpfully distance the Tory party from the dastardly Conservative policy at the time, which saw Douglas Hurd argue against aiding the Bosnian Muslims.

This week William Hague is visiting Bosnia, trying to highlight the problems in the country 13 years after the Bosnian War that saw 100, 000 civilian die. His visit provides welcome attention to the country’s slide towards conflict; while he can helpfully distance the Tory party from the dastardly Conservative policy at the time, which saw Douglas Hurd argue against aiding the Bosnian Muslims.

So what is happening in Bosnia? A lot – but hardly any of it is particularly positive. Bosnian Serb Prime Minister Milorad Dodik, a moderate-turned nationalist, has adopted a secessionist agenda. His long-term policy seems clear, the peaceful secession of the Serb province as Milo Djukanovic did it in Montenegro. For now, he tears strips of the fledgling Bosnian state, gradually transferring power to his provincial capital while he bides his time. Last year, he forced the EU to back down over its demands that the country reform and centralize its police. More recently he has voiced threats to “take back Brcko District” for the Serbs.

The nationalism and fear that began the war in 1992 has been reinvigorated, and the downward spiral is accelerating, with Bosniak and Croat nationalism on the rise, as seen in the recently-held local elections. It may have been a long time since Bosnia was threatened by large-scale violence – and this remains an unlikely scenario today – but a deterioration of inter-ethnic relations, officially-sanctioned racketeering and further social and economic dislocation could create the conditions for flashpoints, gangsterism and violence.

The problem for the Shadow Foreign Secretary is that he is left simply calling for the international community to stick with it, rather than develop any particularly innovative solutions. Hague is constricted because any new ideas require thinking through what the EU needs to do differently, now that the US wants to hand responsibility for the region’s future over to the 27-member bloc. This, for obvious reasons, is difficult for the Tory politician. If he wants the EU military force in Bosnia to remain in place in order to guarantee security does that mean he backs the kind of military deployments that it represents? If he wants it to act more robustly, is he willing to deploy British forces? If not, what is he willing to give European allies as a quid pro quo for them deploying forces? More support for ESDP generally, as some of them will demand?

What about the political issues? The prospect of European integration has been crucial to the little progress Bosnia has made. But the Irish rejection of the Lisbon Treaty and the reaction of European leaders has created the impression of the EU being distracted and vulnerable to the “enlargement fatigue” that occurred following the Dutch and French rejections of the Constitutional Treaty. This, in turn, will reduce the EU’s ability, at least in the short-term, to push Bosnia’s politicians to reform. Will William Hague unequivocally say he thinks Bosnia belongs in the EU to provide the bloc with the necessary leverage to push reforms? If he does so, how does he intend to overcome a clear French view that the bloc should not be enlarged further until its institutional structures have been reformed?

A few weeks ago former Europe Minister Denis MacShane wrote that the Tories have no foreign policy because they have no Europe policy. That is ridiculous. Foreign policy is far more than EU policy. But the Shadow Foreign Secretary’s visit to Sarajevo highlights what can be called the Tories’ “Bosnia Paradox” – that when it comes to developments on the fringes of the European continent, where U.S involvement is likely to be limited and the EU the preferred policy instrument, the party’s euro-scepticism cuts against its own policy goals.

Comments