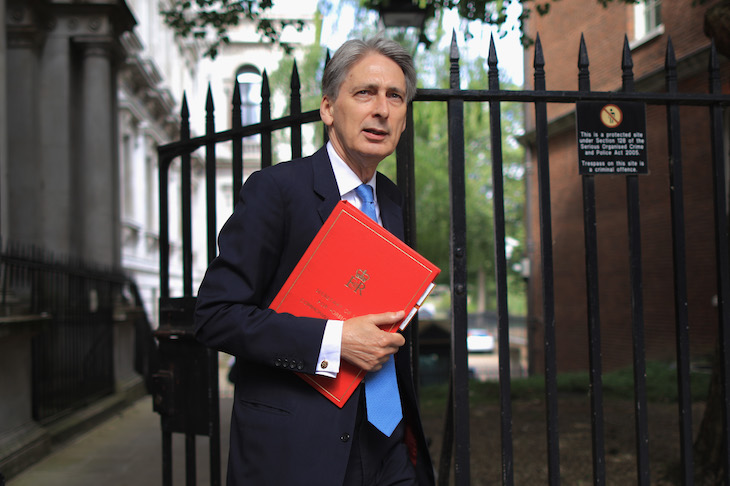

Sometimes in life the biggest risk you can take is to play it safe. This is the predicament of Philip Hammond as he approaches the Budget next month. If he adopts a safety-first approach, it will almost certainly go wrong and he’ll be forced into a credibility-draining U-turn, as he was in March. His best hope is to be bold, and to hope this generates enough momentum to carry him over any bumps in the road.

The two longest-serving chancellors of recent times have relished the theatrics of Budget Day. Both Gordon Brown and George Osborne loved pulling a rabbit out of the hat at the last minute, wrongfooting the opposition and grabbing the headlines. Hammond isn’t like that. He is more cautious and technocratic, with remarkably little interest in political strategy for so senior a politician.

But for him to adopt a cautious approach to this Budget would be a mistake. First of all, he needs to find money for several politically difficult items. He must plug the gap created by his abandoned National Insurance increase for the self-employed, find a way to pay for the tuition-fees freeze announced at Tory conference — and, crucially, honour the financial commitments that Theresa May made to grease the wheels of her agreement with the Democratic Unionist Party after she lost her majority at the election. And he has do all this against projections for the public finances that will look worse than previously expected because of the Office for Budget Responsibility’s expected downgrade to productivity growth.

This would be a difficult hand for any chancellor to play. But Hammond is painfully short of support. He hasn’t set about building the kind of solid Treasury operation that both Osborne and Brown constructed. Admittedly, they both did this because they wanted to move next door, whereas Hammond is one of the few Tories who is not planning a leadership bid. But he still needs a stronger operation. As even one of his most loyal allies admits ‘it is a very weak set-up’ in the Treasury. Worryingly, two of his more senior advisers are leaving after this Budget, suggesting that this problem is likely to get worse, not better.

Hammond isn’t short of enemies either. His negativity on Brexit has alienated him from many of the papers that endorsed the Tories at the last election; just look at the Daily Mail’s thundering attacks on him recently. He is also short of allies in cabinet, where his problems extend far beyond his relations with the Brexiteers. Several Remain-voting ministers find him intellectually condescending and are irritated by his political tin ear.

If the Budget is genuinely radical, Hammond and his defenders will be able to dismiss the inevitable rows over minor measures by emphasising the big picture. It will also rebut the argument that he is just a details man; that he is really a Chief Secretary to the Treasury — the job he would have had if David Cameron had won the 2010 election outright — masquerading as Chancellor of the Exchequer.

The task that should have occupied the Treasury since the referendum vote is working out how to make the UK competitive outside the single market and the customs union. Instead, it has wasted time fighting a bureaucratic rearguard action trying to keep Britain in both, not realising that in political terms the referendum had essentially settled these questions.

Hammond himself used to have an answer to this. In an interview with the German press at the start of the year, he warned that if the UK lost access to EU markets, we would change our economic model to regain competitiveness. As he put it, ‘you can be sure we will do whatever we have to do’. But by this summer, he was backing away from this approach in an interview with Le Monde.

In the Brexit negotiations, the UK must aim for a deal that lets us diverge from the EU. There is little point in leaving if we are simply going to shadow the old regulatory approach. The EU, unable to move quickly, is unsuited to regulating fields where technology is rapidly changing. So the Budget should aim to show that in the years ahead Britain will be a far better place than the EU to work, for instance, on gene editing, artificial intelligence and fintech.

Upgrading the UK’s physical and digital infrastructure is also vital to improving our competitiveness. Hammond has long been aware of this. In private, he has repeatedly made clear that in a downturn he’d favour infrastructure spending over a VAT cut — as at least the country would have something to show for it afterwards.

But he probably won’t go for infrastructure stimulus now. Colleagues say he remains deeply worried about the impact on the economy of leaving the EU, so he is unlikely to want to use up the fiscal headroom he has created for dealing with any Brexit-related slowdown. This also means he is unlikely to wholeheartedly embrace Sajid Javid’s innovative plan for the government to borrow £50 billion to fund a mass house-building programme.

Javid’s plan has the merit of being proportionate to the size of the housing crisis, unlike past Tory efforts. It also recognises that a broken housing market cannot be fixed by the market alone. The housing issue is distorting our economy, our society and our politics. There is a clear case for government action to fix the problem as fast as possible. Borrowing to build houses is not the same as borrowing to fund day-to-day spending, or even to build new schools. Gordon Brown’s debasement of the word ‘investment’ shouldn’t put Tories off the idea of the government borrowing to invest.

A government-commissioned house-building programme would be a sensible strategy, especially if combined with planning reform designed to ensure that enough houses are built where people want to live. It would give the government a domestic purpose beyond Brexit as well as supplying an economic stimulus that would help the UK through the uncertainty that the next few years will inevitably bring.

James Forsyth and Anne McElvoy discuss Hammond’s budget on The Spectator Podcast.

Comments