You might have missed this because it hasn’t exactly been saturated with media coverage, but this week is the 200th birthday of Britain’s railway. In fact, it’s the 200th birthday of all railways, since we invented them.

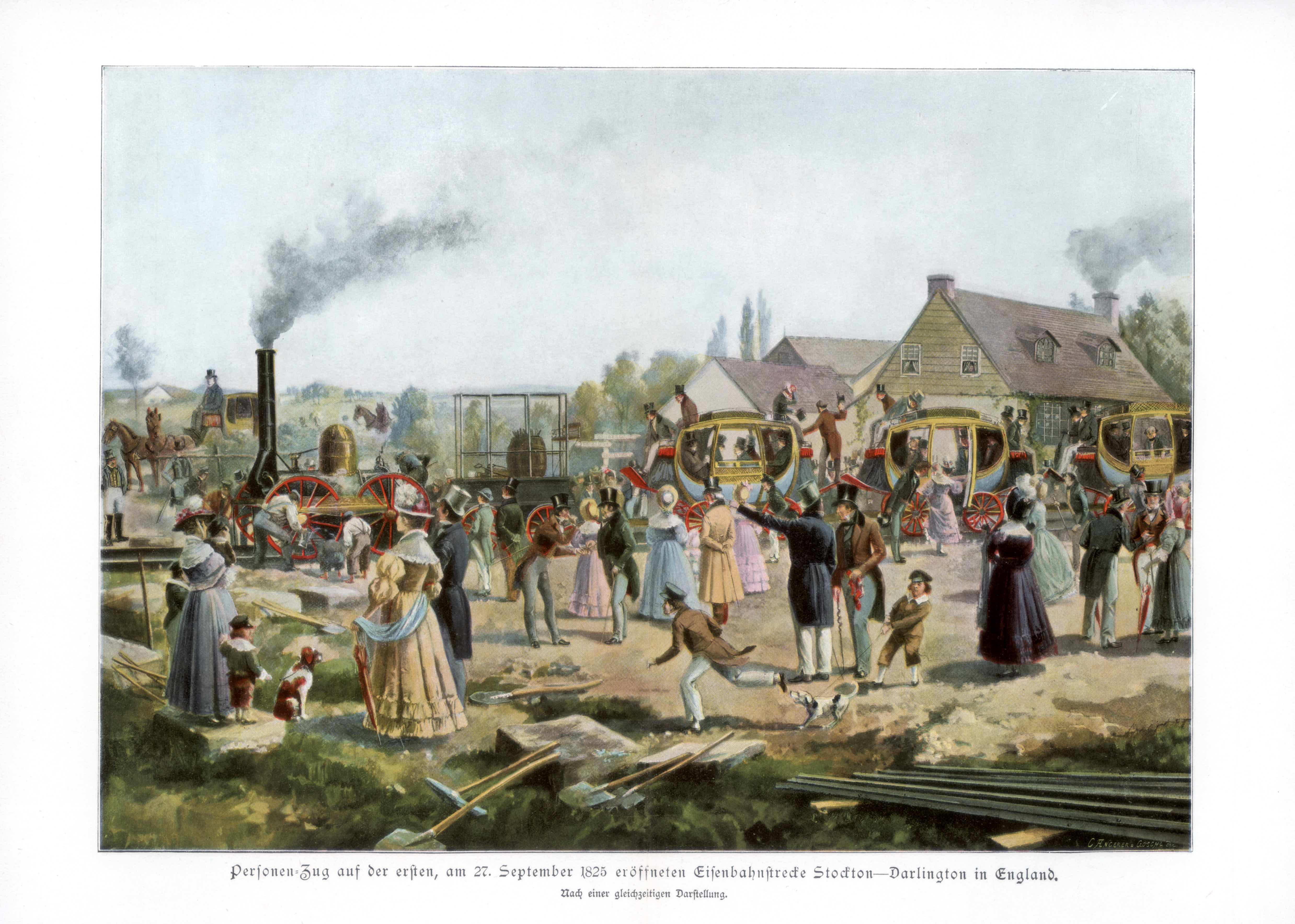

It was on 27 September 1825 that service began on the Stockton and Darlington Railway. Travelling a distance of just eight-and-a-half miles at about 15mph, the world’s first public commercial rail service arrived to a crowd of 10,000 and – as would become a characteristic feature of future British rail travel – was delayed by half an hour due to engineering problems.

Yes, the worldwide rail revolution began in the north-east of England – the Silicon Valley of rail. I know, not since H.G. Wells decided that the Martians should begin their interplanetary assault on Earth by taking out parts of Surrey has provincial England been so fêted. But it really happened. And as a result of what took place in Darlington that day – thanks to the genius of the concept and a thing called the British Empire which we don’t like to crow about any more – the world now has around 800,000 miles of railway, and billions of railway journeys are made each year.

So, what a gift that was. And thank you to George Stephenson, the Northumberland-born engineer and ‘father of the railways’ who together with his son, Robert, put the steam with the trains and the tracks to make it all happen. Of course, they were standing on the shoulders of giants such as the Cornish rail pioneer Richard Trevithick, but they were the ones who did it. Their Locomotion No. 1 hauled those first passengers two centuries ago, and was built at their works in Newcastle – works which would go on to build 3,000 engines by 1900 alone and eventually formed part of the rail division of the great British industrial conglomerate General Electric Company (along with a dozen other venerable names in the business). These would then merge with Alstom of France in 1989, before the GEC component of it was broken up and sold off in 1998.

Which makes you proud (at least up to the point where we sold it off), but the truth is we do still design and build trains in Derby (Alstom boasts that this is the UK’s ‘largest train factory’), and Hitachi also makes trains in Durham. And this matters, because despite inventing and pioneering computers, we no longer build many of them here, so at least we do turn out a few trains. Perhaps it’s beside the point, though, because like computers, antibiotics, democracy and football, railway is a gift that we have given the world – and it’s a gift that each of us can continue to enjoy, too. Because nothing beats rail travel.

Travelling by train is easily more enjoyable than any species of commercial air travel, with its relentless queuing, absurd belt-and-shoe removal and endless stupidity about laptops and certain quantities of fluids. The train is also far better than travelling by car, because on a train you can actually work or read or drink as much as you like. You can walk around and, of course, you get to avoid service stations, which easily qualify as the most repellent places in Britain. Trains are often faster, greener and, most importantly, they will broaden your horizons in a way that driving just doesn’t seem able to match.

The world’s first public commercial rail service was delayed by half an hour due to engineering problems

Take the train from London King’s Cross to Edinburgh, for instance, and you are transported pell-mell through time and space. Raised on railway embankments you have a front-row seat on a cacophony of geographies ranging from farmland and pasture to villages, towns, light industry; you pass vast cooling towers, suburbs, cities – through the centres of York, Durham and Newcastle upon Tyne – spying cathedrals, castles and a coastline dotted with gems such as Alnmouth and Berwick-upon-Tweed, Richard III’s great gift to England. Travelling by train from London to Edinburgh isn’t just about getting from A to B: it’s a high-speed masterclass in British anthropology, geography and history. Before you know it you’re marvelling at the landscape, gawping through the window, a tourist in your own country.

And every now and then there’s the thrill of the speed when the driver puts his or her foot down. There’s a section outside London where the tables shake and you know you’re doing well over a ton (the trains can do 140mph, apparently). And below there’s the satisfying rhythm of the rolling stock on the tracks and something reassuring about the fact that we’ve been thumping up down these rails (though hopefully not these exact rails) since the line opened between London and Edinburgh in the late 1840s. In the days of the Flying Scotsman it took six hours to do the 393-mile journey between Edinburgh Waverley and King’s Cross. Now it’s a smidge over four. Perhaps there’s life in the old country yet.

But in a way, the time is irrelevant, because when you’re on the train, you’re on the train. It becomes the whole, rather immersive experience. And it’s a joy that you don’t need to be a former Conservative defence secretary with a penchant for nifty jackets to appreciate.

As well as what’s outside and what the Futurist manifesto called ‘the beauty of speed’, there is the spectacle of what is inside: the great British public. Observing our fellow man and woman in their unguarded moments is a significantly rewarding and much overlooked aspect of rail travel. You don’t overhear the intimate personal problems of perfect strangers in the ‘Quiet carriage’ when you’re on the M6 toll road, nor do you have the pleasure of being forced to listen to someone’s boorish sales negotiations. But that’s all part of the pleasure of rail, or at least it can be.

In 200 years, railways have given the world so much: timetables, the first world war (if you believe your A.J.P. Taylor), the concept of commuting itself, plus commuter towns and the resulting notion of working from home. They’ve given us dining cars, Thomas the Tank Engine, Brief Encounter and Murder on the Orient Express. Where would Crewe be without the railways? Letting the train take the strain on iron tracks has in fact enabled the creation of the industrial civilised world as we know it. It’s been quite a journey, and it all began 200 years ago this week on an eight-mile line between Stockton and Darlington – something we should all be very proud of and grateful for.

Comments