Hindsight is the easiest weapon to employ in politics — as Keir Starmer of all people should know. When you have witnessed events unfold already, it is simple to point out what politicians should have done. Yet when it comes to post-Corbyn Labour, some mistakes have been made that may just have been avoided — and hindsight is not required to reach that conclusion. The clues were there this time last year.

Starmer has moved too slowly and has made the error that many unsuccessful Labour leaders tend to make: assuming that the party requires less mending than is actually the case. Sir Keir has employed the same logic that Gaitskell, Miliband and Brown did, thinking that with a few minor tweaks here and there Labour could win again. Suspending Jeremy Corbyn was a momentous symbol — but that is really all it was, a symbol.

Starmer started his premiership by bringing in a broad constellation of Corbynites including Rebecca Long-Bailey, his former socialist challenger. Take Dan Carden, a one-time bag carrier to Corbyn loyalist Len McCluskey, he was initially drafted in to serve in the shadow business team alongside Wes Streeting, a man who once described Tony Blair as his political hero. The rationale was clearly to keep all the different factions inside the tent. But that attempt failed. Most of those Corbynites have now fallen away from the front bench — either at Starmer’s own hand, as in the case of Long-Bailey, or have resigned by their own free will, as in Carden’s case.

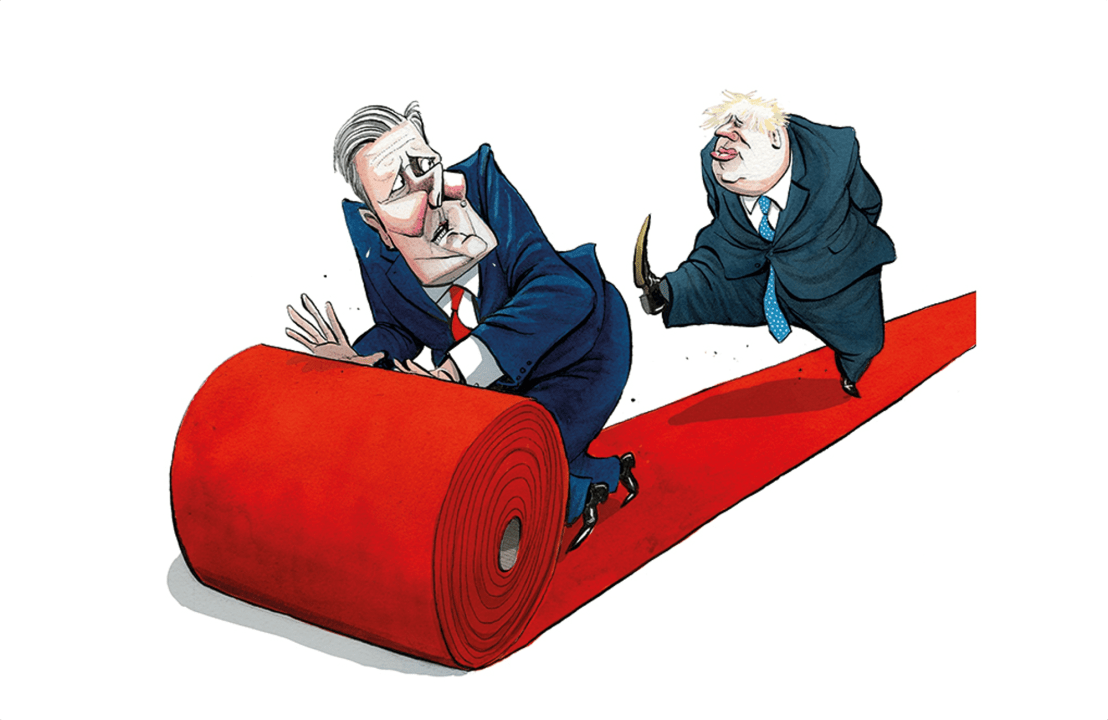

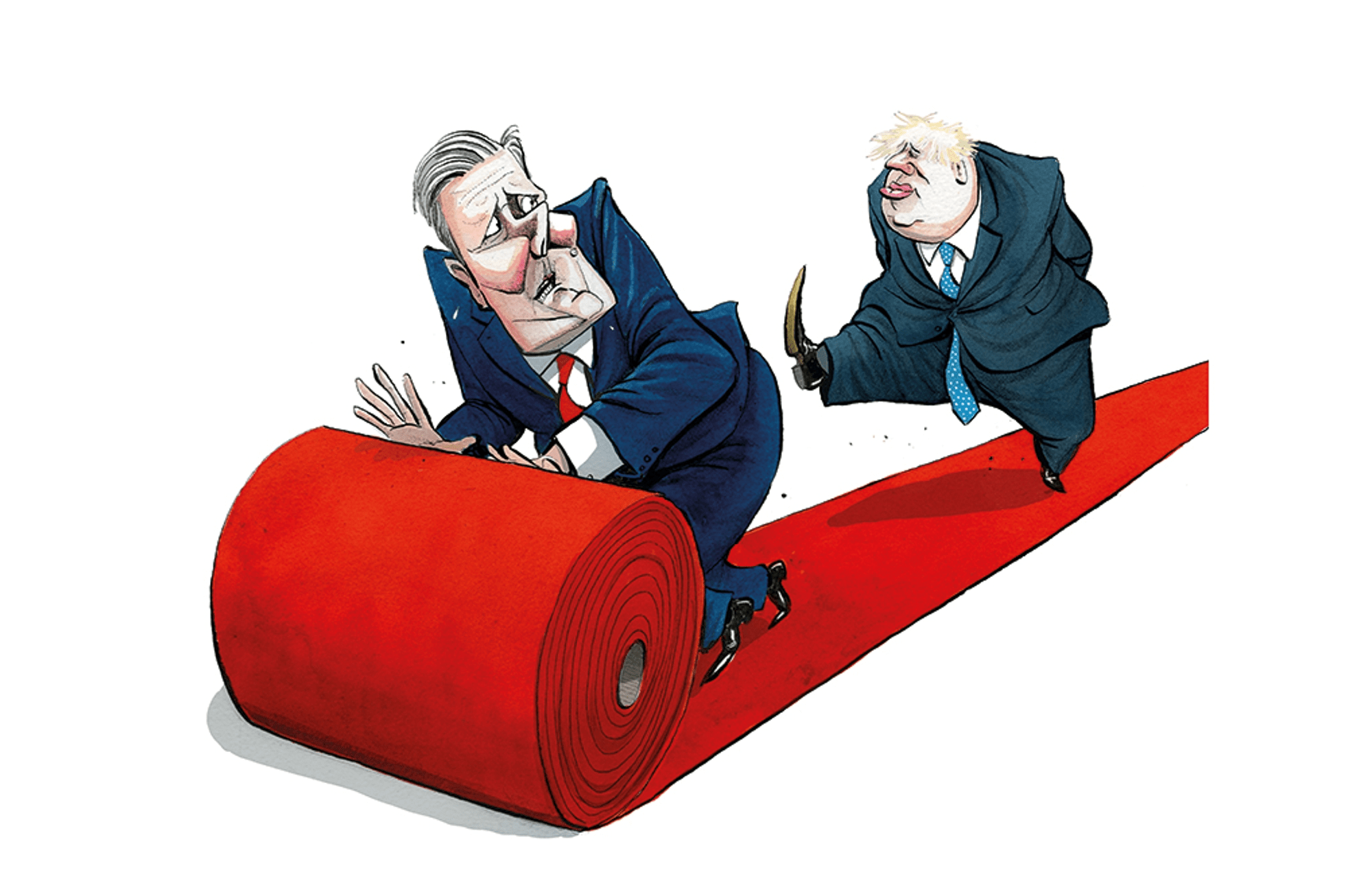

Starmer’s plan seems to have gone like this: present the new leader as a solid, respectable, middle-of-the-road chap whose competence will be pitted against Boris Johnson’s ruffled hair insouciance. Embrace patriotism and some socially conservative values but in a slightly half-hearted fashion. Avoid policy announcements and instead focus on making the right noises.

Suspending Jeremy Corbyn was a momentous symbol — but that is really all it was, a symbol

For this to have had any chance of success, Starmer needed his party to hold together. Yet it seems reasonably obvious that in deploying his chosen strategy, a large section of the party was never going to wear it. Labour’s left, enlarged by five years of Corbyn, is unable to accept any rightward shift. Starmer should have recognised that his attempt to move away from Corbyn’s values and towards what the average Briton believes was always going to trigger a civil war. Rather than pretending it wasn’t going to happen, he should have accepted it and landed the first blow. Perhaps he could have learnt from his ultimate rival, Boris Johnson, and ejected the socialist radicals from the party.

The second part of Starmer’s plan was to wait for Johnson to visibly screw up either Brexit and the pandemic (preferable both). But however much Labour activists remain convinced the Prime Minister did just that, the public disagrees with them.

Keir’s team underestimated Boris. They thought they could position themselves in a place where disaffected Tory voters — frustrated at the failure to manage Brexit and Covid — could fall into Starmer’s hands. All he had to do was send the right signals and voters would abandon the sinking Tory ship. This lighthouse strategy might initially have seemed like a fair bet. But the problem is the ship isn’t sinking.

Even if Boris had stumbled, Starmer needed to take some big risks right off the bat. Suspending Corbyn while trying to shackle together opposing factions wasn’t enough. In order to tell a coherent story about where you would take Britain, the party telling that story needs to be coherent. Starmer needed to change Labour in a fundamental way.

How could he have done this? Here’s a bold suggestion: Starmer should have used the good will he had among all portions of the moderate centre-left when he first became Labour leader to unite them all under one party banner. He should have tried to get the Liberal Democrats and the Greens to melt into Labour. It would have been difficult, and there is a high chance that he would have failed, but without that kind of realignment his party seems all but doomed. By bringing in Lib Dem MPs and elements of the Green movement, Starmer could have remoulded the Labour party permanently.

In doing so, the new Labour leader could have erased the antagonistic politics of the worker vs the boss class, that 20th century hangover that speaks in the language of nationalisation, picket lines and industrial strife. Labour could have transformed into what it has been trying to be for the last half century: a successor to the Liberal party, comfortable with capitalism but with a social and ecological conscience, institutionalist rather than revolutionary.

If you doubt whether the Labour party, the Liberals and the Greens could have merged, look at how the Labour party subsumed the co-operative movement. Until 1927 the Co-op party ran candidates against Labour, winning a handful of seats and splitting the left-wing vote. Labour made a pact with the smaller party that they wouldn’t run directly against each other. Now MPs can be selected as both Labour and Co-operative party, with 26 Co-op parliamentarians currently in the Commons. New Labour and the Lib Dems also came extraordinarily close to forming something similar at the turn of the century. Paddy Ashdown wrote in his diaries about his secret pact with Blair prior to 1997 in which the two parties expected to go into coalition. Even after Blair’s landslide election win, the Lib Dems were invited to join a cabinet committee that came close to seeing the Liberals fold into Tony Blair’s post-socialist Labour party. That plan was ultimately stymied by the Blairite voice of old Labour, John Prescott.

If Starmer had succeeded in bringing together the Lib Dems and the Greens, three things would have been achieved. One is that it would have given Labour a much better shot at winning the next general election. The anti-Tory vote would no longer be split, at least England and Wales. Of the 91 seats the Lib Dems came second in at the 2019 general election, 72 are held by the Tories.

Two, it would have made it much harder for the Corbynistas to take the party over again should he lose that election. Labour would have new Liberal MPs, not to mention the possibility of a couple of Lab-Greens in places like Bristol should the parties have agreed a pact. The party’s voter base would skew more towards the home-owning, progressive suburbs and away from the more radical, younger city centres. The power of the socialist revolutionaries would have been diluted.

Third and finally, it would have guaranteed Starmer a legacy. Even if he lost the next election badly, he would forever be the leader who ended the centre-left split, one that had raged in one form or another for a century.

I know many Labour people will scoff reading this idea. And this gets to the heart of the party’s problem — it needs to evolve, it needs to change, but no one within it wants to do that. Or at least, no one within the Labour party wants to change it in any way that would be electorally beneficial. In order to win a general election again, Labour is going to have to become a much bigger tent than it currently is. Part of the problem is that they don’t exactly know how to do this, but a much bigger issue is that no one seems to want to change the party in a way that would make this a real possibility.

Starmer might not only have blown his chance for victory in an election, he might also have missed his opportunity for a Kinnock-esque legacy of saving his party. The most likely trajectory is that he loses the next general election, resigns and then watches the party sink back into the Corbynista mire, his leadership a mere blip on a downward trajectory for Labour. Starmer might have missed the last chance to save the institution of the Labour party, what remains of that awesome election seizing machine of the early 21st century. Trying to bring Lib Dem MPs and Caroline Lucas into Labour might appear fantastical to some — but it is exactly the type of radical realignment needed to stop Starmer from becoming Labour’s version of William Hague.

Unfortunately, it seems it may already be too late. Starmer is stuck reshuffling the deck rather than changing the game. All he can do is hope Johnson slips up badly enough to make the public desperate for any other option apart from the Tories. It could have been so different if only Starmer had been bolder from the start.

Comments