A new report from the field of human origins had sub-editors reaching for their hyperboles. A million-year-old skull, we have learnt, has rewritten humanity’s story. The finality of this is misleading, but there is nonetheless something going on here.

If Neanderthals, Denisovans and sapiens evolved away from each other a million years ago, there must have been earlier human forms not yet seen

For decades, Chinese archaeologists have been investigating a site known as Yunxian, beside a tributary of the Yangtze river. The researchers have been rewarded with human fossils – to date, three skulls around a million years old. These bones have been preserved well but the skulls have been crushed. As a result, comparing them with other fossils, and therefore finding exactly which species they might represent, has been a challenge.

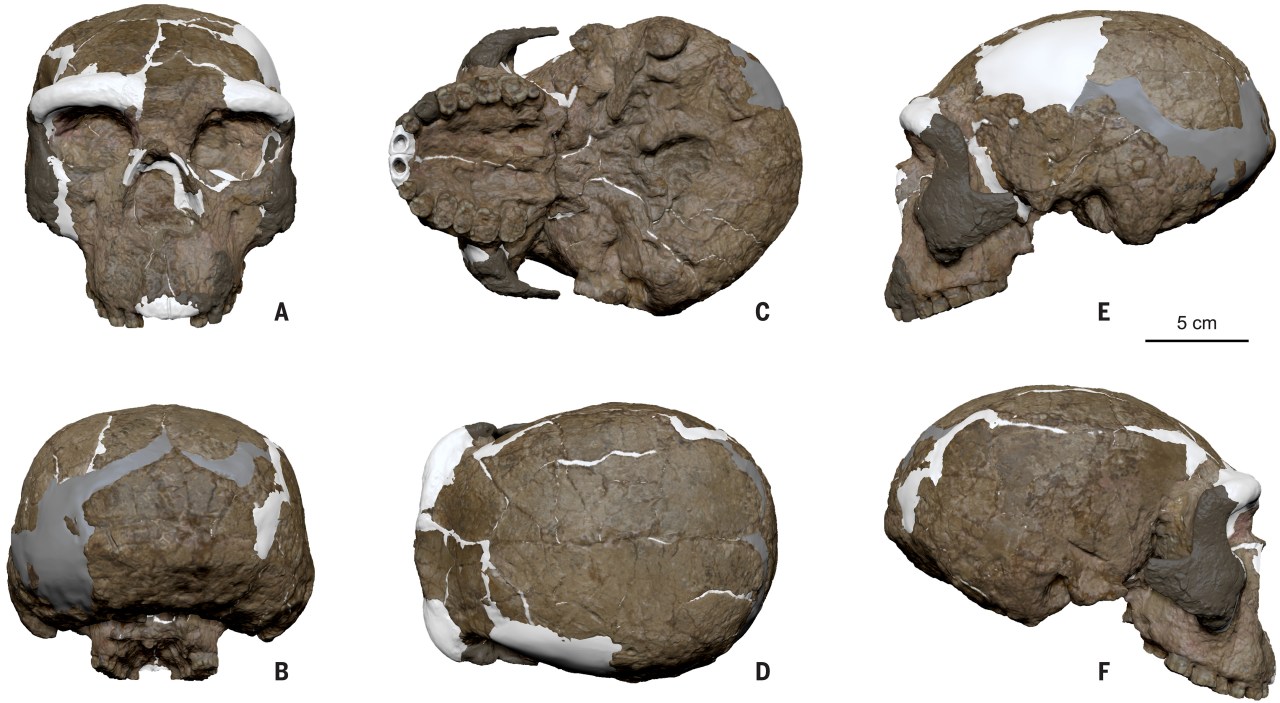

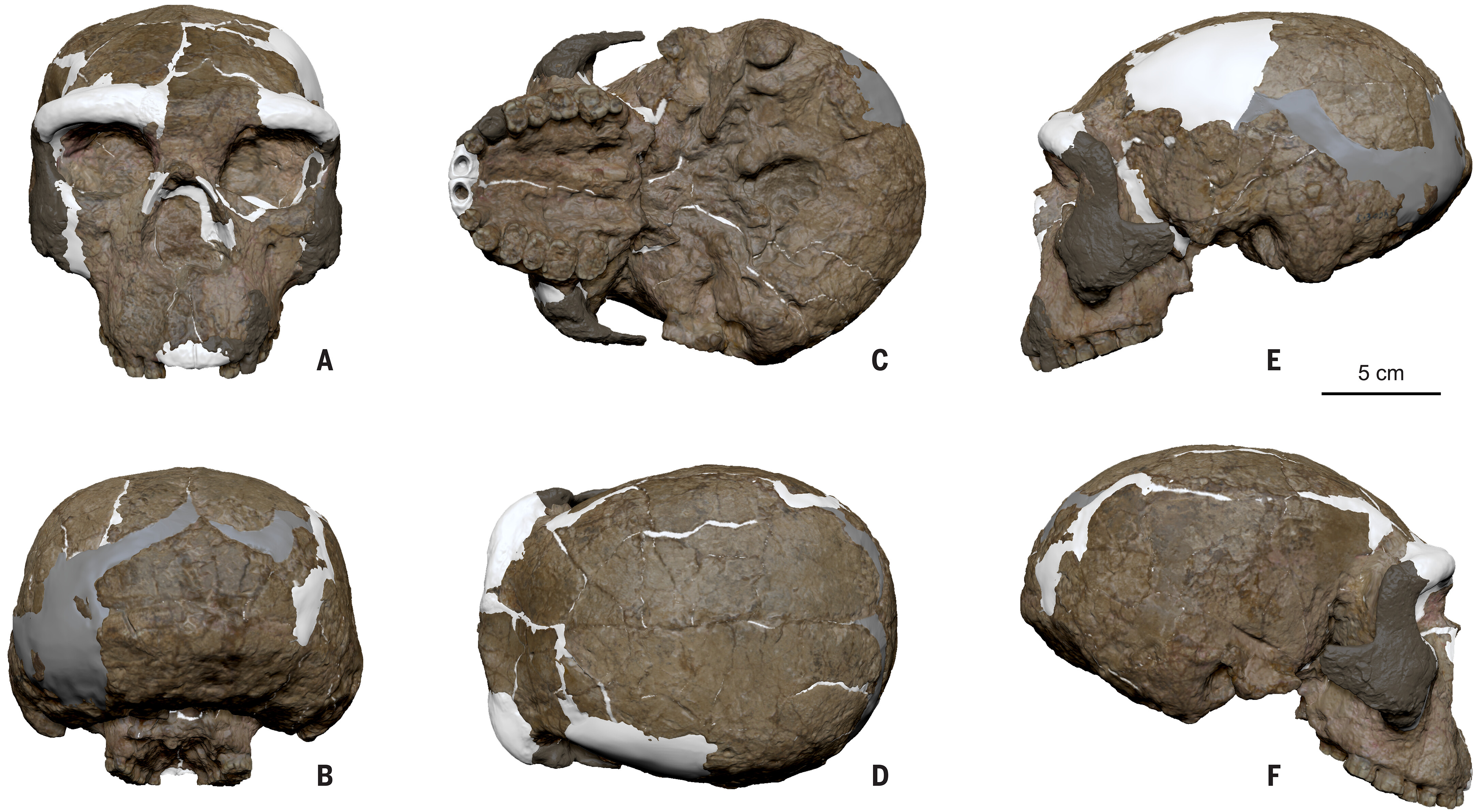

The skulls are broken, but not distorted: most of the right bits are in the right shape, just not in the right places. In a new study, published in the journal Science, a dozen Chinese archaeologists and scientists joined by Chris Stringer of London’s Natural History Museum, claim to have overcome this difficulty using cutting edge digital imaging and computer modelling to put them back together again. After doing so, they have revealed that a nearly complete skull found in 1990 is something no one had predicted: a creature that suggests our own family tree, made up of Homo Sapiens, is twice as old as previously thought. What’s more, this early ancestor of ours was walking around Asia, but apparently not Africa. How did we get here? And what does it tell us about ourselves?

It has long been agreed that humanity’s deep origins lie in Africa. A major genetic study released earlier this year found that humans and our chimpanzee ancestors separated from each other a little over five or six million years ago. What happened next on our side has become complex, if not downright confusing. The number of apparent species, and which parts of Africa, Europe or Asia they occupied and when, has come under constant scrutiny.

The first close human lookalike appeared in Africa around two million years ago in the form of Homo erectus. Humans soon spread into – or appeared as related species in – parts of Europe and much of Asia. Making sense of the rare and fragmentary fossil evidence has been helped by genetic studies, which have confirmed the later and simultaneous presence of three species across Eurasia by around half a million years ago: Neanderthals – Homo neanderthalensis – in the west, Denisovans in the east, and the more widespread Homo sapiens occasionally breeding with the others. Ancient DNA and proteins recently identified a Chinese skull known as Dragon man as the first known Denisovan face, and Denisovans have been described, somewhat controversially, as a species known as Homo longi.

The new study extends this picture with further complexities and a longer history. The Yunxian skull, say the scientists, has a mix of ancient and newly acquired features. Parts recall erectus fossils, while its brain is larger, and the cranium’s face and lower back instead compare favourably to Dragon man – or even, says Stringer, Homo sapiens. The skull’s age, however, independently shown by geology and the particular ecosystem of mammals in the site’s well-preserved remains, suggests it comes from the erectus era.

The team resolves these apparent contradictions by rethinking the historic human landscape. In this new view, ancestral Neanderthals, Denisovans and sapiens separated a little over a million years ago, rather than around 500,000 years ago.The theory posits that Neanderthals, Denisovans and sapiens were alive at the same time as Homo heidelbergensis (traditionally thought of as the common ancestor of Neanderthals and sapiens) and later Asian Homo erectus. In other words, for hundreds of thousands of years our planet hosted five highly intelligent, large-brained types of human. In the long run, only one survived: us.

What does this mean for other human fossils we have found? Homo antecessor, for example, a species identified from remains in a Spanish cave at Atapuerca, has been proposed as an ancestor to heidelbergensis; this would put it at the root of the group that includes us and Neanderthals. That has always been controversial (it’s the excavators’ idea), and in the new analysis, the antecessor species is said to belong to the Denisovan group – and so, ultimately, doomed to extinction. Genetic studies have suggested different relationships, separating Dragon man from its African ancestors a relatively recent 700,000 years ago.

And then there are the fossils we don’t have. If Neanderthals, Denisovans and sapiens evolved away from each other a million years ago, there must have been earlier human forms not yet seen. The placing of their common ancestor among the intertwined branches of early human trees is unknown. It all opens up a quest for previously unsuspected types of fossils.

It’s the bigger picture here which is particularly exciting. Only archaeology can help us understand the nature of all these creatures: how they behaved and thought. Thirty years ago, archaeologists talked of a revolution marked by the sudden appearance of sophisticated art in Europe – indication, it was said, of the arrival of the modern human mind a mere 30 or 40,000 years ago. Evidence from the ground has since shown such developments also occurred far beyond Europe, and over a longer time span.

If early Homo sapiens evolved a million years ago, as this study suggets, when did individuals start to make art? At what point did they become ‘modern’ – and why? Could this have happened first in Asia, rather than Europe or Africa, and again, if so, why? Sooner or later we’ll get to answer such questions. Doing so will take us into a new, deeper understanding of who we really are.

Comments