When I was 13, my school cricket team received a visit from a top professional cricket coach, an intoxicating visit from the big leagues. I tried to hear what the great man was saying as he watched us, how he advised our teacher. ‘Never praise kids — they only mess it up next time,’ I overheard him say. After pausing to berate me for a below-average cover drive, he whispered to the teacher, ‘It’s different with criticism — that really works.’

Like a typical cocky teenager, I longed for a clever riposte. Perhaps fortunately, I didn’t have the intellectual insight to deliver one. But last week I met up with the man who did — Daniel Kahneman, professor of psychology, winner of the Nobel prize for economics and author of the newly published Thinking, Fast and Slow.

In the late 1970s, he was teaching flight instructors in the Israeli Air Force about the psychology of effective training. He told the instructors that praise rather than criticism was the best way to help the cadets improve. An experienced instructor disagreed with him: ‘On many occasions I have praised cadets… the next time they usually do worse. On the other hand, I have often screamed into a cadet’s earphone for bad execution, and in general he does better on his next try.’

Kahneman realised that the instructor was making a mistake. If a cadet did something better than normal, his next attempt at the task would in all likelihood not be as good, whether or not he was praised. In the same way, if he performed unusually badly, his next attempt would probably be better, whether or not he was criticised. The trainer was attaching a causal interpretation to the fluctuations of a random process; simple regression to the mean. Kahneman had been teaching regression to the mean for decades, and had the scholarship to understand how the instructor was being misled by his intuition. He knew it was possible to infer wrong explanations even from accurate observations.

‘That was a true Eureka moment,’ Kahneman explains to me, looking anxiously in the direction of a pianist who is threatening to start playing in the lobby of his central London hotel. ‘It was like being in a place for the first time that nobody has seen before. I enjoyed that quite a lot.’ Much of his career has been spent testing similar cases, when intuition seems sound but is logically and statistically misleading. Kahneman is the master student of human error.

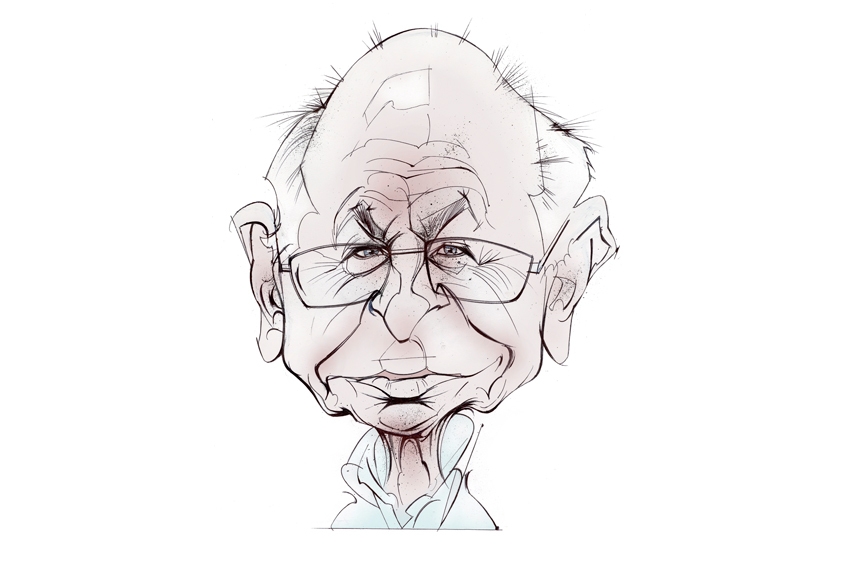

Seventy-seven years old, soberly but neatly dressed in a grey suit with a dark green tie, with immaculate manners and a mischievous expression, Kahneman speaks in measured, precise sentences. A lifetime of studying overconfidence has made him careful to avoid the same mistake himself. His book distinguishes between two distinct modes of thinking. System one operates automatically and quickly, with little effort and no sense of control. System two requires reflection, concentration and complex calculations.

The problem comes when we use system one in an inappropriate environment, when we use intuition when it cannot be trusted. ‘Type one is specialised for making instantaneous connections. You get a cold, you ask “Where did I catch it?” We’re constantly looking for causals and telling stories. It’s really absurd.’

Many of Kahneman’s experiments were designed to disprove his intuitions, to catch himself indulging misleading hunches. As a professor, he suspected himself of marking exam papers lazily by giving undue weight to the examinee’s first answer, sticking with a snap judgment. It’s called the halo effect: once a good impression exists, it is difficult to dislodge. His solution was to stop marking exam booklets beginning to end. Instead, he marked the first answer of every student, writing each mark on the inside back page of the booklet where he couldn’t see it. Then he marked all the second answers, and so on. As he puts it, he wants ‘to decorrelate error’.

Kahneman had a distinguished collaboration with Amos Tversky. ‘We posed riddles to each other and invented questions in an attempt to elicit intuitions which were wrong.’ In a famous experiment, Tversky tested the basketball cliché that a player gets a ‘hot hand’ when he shoots three or four consecutive baskets, making him more likely to succeed with his next attempt. There is no such thing as a ‘hot hand’. Some shooters are more accurate than others. But the sequence of successes and misses is no different from those achieved by random tests. Conclusion: coaches should give the match-deciding shot to their consistently highest percentage player, not to the guy on a hot streak that day.

As I’m hearing about the flaws of intuition, I can’t help wondering if there are some dangers to the Kahneman approach. As a cricket captain, I had to make dozens of decisions, usually on incomplete evidence. Kahneman-type thinking would have made me mistrust my gut instinct. Even if I’d made better decisions, I would have radiated less confidence in them — and leadership is often about appearances as much as reality. After all, there are two elements to any plan. The first is the decision, the second is the execution — and your conviction that it’s the right idea can affect the execution.

I’m quite surprised that Kahneman agrees. ‘Being an optimist is clearly very good in the context of execution. I agree that confident leaders attract resources and gain loyalty. Confidence and optimism are wonderful things to have, but the cost can be that people take risks that they shouldn’t with the lives of other people.’

Given his awareness of those risks, could he have been a man of action, a politician, a general or a CEO? ‘I couldn’t be any one of those things because I second-guess myself too much. Leaders are selected for the ability to resist second-guessing themselves.’ But he can’t resist adding a Kahneman refinement. ‘I think we penalise reflective leaders because they appear to lack decisiveness. People confuse decisiveness with speed. It’s rare to hear a good word about President Obama these days. But actually he is both slow and decisive. He tries to be reasonable and that’s not what we want in a leader.’

We may not want it in a leader (though we may need it). But we definitely want it an academic.

Ed Smith is a writer for the Times.

Comments