Something I have long noticed is how, the moment they leave office, many politicians suddenly undergo a strange transformation where, overnight, they become much funnier, more likeable and intelligent. Two years after he had failed in his presidential bid, Bob Dole appeared on British television to comment on the American mid-term elections. To my astonishment, he was one of the wittiest people I have ever seen, delivering a series of perceptive barbs with a snarky, very British sense of ironic humour. I asked an American friend why we never saw this side of him when he campaigned for the presidency: ‘Oh, you can’t do that kind of humour in the US — it makes you look cruel.’ I’m not sure he would say that now.

Michael Portillo is much more interesting now than when in power. Watch Nick Clegg in conversation with Jonathan Haidt on intelligencesquared.com and you will be awestruck. The same applies to programmes on the financial crisis: retired bankers are self-deprecating and honest; working bankers look shifty.

I suspect a little bit of is it down to dress. The standard-issue politico-business suit used to be a mark of respectability: now we instinctively associate it with people who need a cloak of anonymity behind which they can dissemble. Here’s some free advice if you’re appearing on television: buy a tweed jacket or, at any rate, don’t wear black or a conventional tie — you then look like a person not a spokesperson. After all, how independent-minded can someone be when they can’t even choose their own clothes?

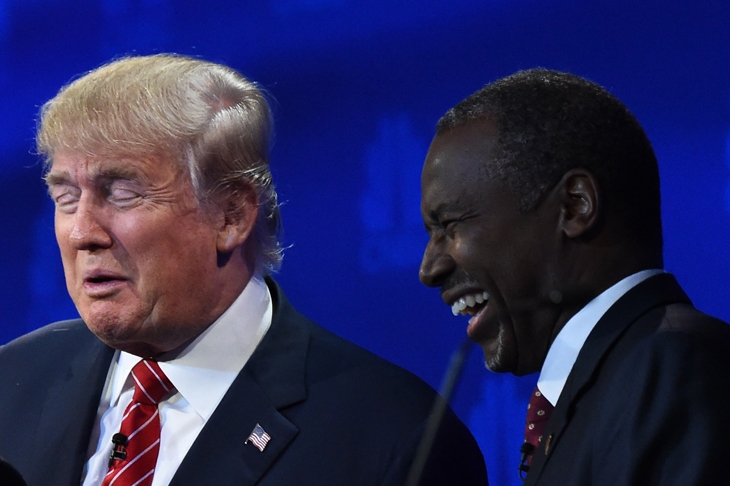

But the larger part is language — the need to stay perfectly on-message and to deliver a few pre-agreed phrases makes perfect logical sense, but at the price of making people sound implausible or even dishonest. The need to pretend everything is under control creates the reverse impression. All over the world, from Beppe Grillo to Trump, we are seeing the rise of people who have a certain plausible randomness to their delivery. Trump’s use of aposiopesis and repeated parenthetic asides made him seem more authoritative, not less — because it made it clear that he was speaking his own mind. It would not surprise me for an instant to discover that there is an evolutionary instinct which causes us to prefer a slightly nasty and authentic person to someone who implausibly pretends to be flawless.

This is sometimes called the pratfall effect. People, men in particular, seem to prefer others who have some visible flaws, or who are capable of self-deprecation. You see this in advertising slogans — ‘We’re number 2 so we try harder.’ ‘Reassuringly expensive.’ ‘Marmite — you either love it or you hate it.’ ‘Good things come to those who wait.’ Or (Salman Rushdie’s) ‘Fresh cream cakes — naughty but nice.’ A claim that acknowledges a downside or trade-off carries more weight, as in that strange phrase ‘This is my mate Dave — he’s a bit of a wanker but he’s great.’

Humour plays a decisive role in honesty too. It allows people to ‘signal intelligence without nerdiness’ and naturally targets dogma, absolutism and self-aggrandisement. More magically still, it creates a parallel universe in which people or groups can change their minds, admit to failings or speak truth to power (the jester) without the dire reputational or coalitional consequences that pertain in the real, unfunny world. Humour allows us, for a time, to place ourselves in a different social network structure where the rules of interpersonal discourse and refutation change: it is, in short, a natural error-correction mechanism, an evolutionary miracle. We need more of it.

So, if you want to see the future of human discourse, book 9–12 November 2017 in your diary and make your way to Ireland for Kilkenomics, the world’s only festival of economics and comedy. Once described as ‘Davos without the hookers’ until the real Davos complained, it is now more commonly billed as ‘Davos with jokes’. Being in Ireland, the standard of conversation from the audience is every bit as high as it is on stage (call me an old Celtic supremacist, but it is no coincidence that craic is not an Anglo-Saxon word).

Bucking the usual retail trends, the lovely town of Kilkenny is also one of the few where pubs still outnumber women’s clothes shops and coffee shops five to one. And, in an interesting power-reversal dress code, the comedians have to wear suits while the economists and other ‘experts’ wear casual dress. Walk into a random pub and you’ll run into Nassim Taleb and Dara Ó Briain, or Deirdre McCloskey and two cast members from Father Ted.

There is a reason why economics is badly in need of healthy ridicule — both of them, interestingly, explained by an economist. John Maynard Keynes made two observations which I think are closely related. Both belong, I think, to the field of evolutionary psychology rather than conventional economics. He observed that there were many people who would prefer to be ‘precisely wrong than vaguely right’. He also said that ‘Worldly wisdom teaches that it is better for reputation to fail conventionally than to succeed unconventionally.’ This refers to human tribalism, where we choose our opinions to minimise social isolation rather than error.

Economics has been badly led astray by these two strong human instincts. The urge to avoid ambiguity and uncertainty to a point where people would rather use the wrong map than no map at all. And the coalitional and reputational instincts which mean that we will instinctively and unthinkingly believe stupid things rather than break ranks with an in-group or coalition to which we belong. The two are connected: the most loyal members of a group are those who question its dogma least.

(I try to solve this problem myself by being passionately and unquestioningly dogmatic about stupid things which don’t matter: I believe the true word of God can only be expressed in 17th-century English, am a great fan of the monarchy and am convinced, without a shred of empirical support, that the drink Dr Pepper has real medicinal powers. The great thing about this is that by clinging to irrelevant certainties, I am free to change my mind about things which are actually important, such as the minimum wage or the need for free movement of labour. The ability to hold irrelevant things sacred is, I think, a great intellectual defence of conservativism.)

Writing recently at edge.org, one of the founding fathers of evolutionary psychology, John Tooby, answered a question which had long baffled me. Why do people on the left get more agitated about transgender bathroom access or hate speech than they do about modern slavery? Tooby explains: ‘Morally wrong-footing rivals is one point of ideology, and once everyone agrees on something (slavery is wrong) it ceases to be a significant moral issue because it no longer shows local rivals in a bad light. Many argue that there are more slaves in the world today than in the 19th century. Yet because one’s political rivals cannot be delegitimised by being on the wrong side of slavery, few care to be active abolitionists any more, compared to being, say, speech police.’ I might also add that many of the practitioners of modern slavery might be a bit foreign–looking, and so in criticising them you run the risk of violating some leftist tribal shibboleth.

Economics has been hugely damaged by these two instincts — but ironically it has achieved its influence precisely because of them. It tends to align itself in coalitions on a left-right axis, which means that politicians can always find a pet economist to support them. And it creates the beguiling illusion of mathematical certainty and internal consistency by making a series of assumptions which would be laughed out of court in a proper science such as physics. This appeals to policy-makers too. It then awards itself an intellectual ‘get out of jail free’ card by blaming the failure of its models on ‘human irrationality’ — rather as though a physicist could blame the failure of a theory on ‘pervy electrons’.

Let me just explain one of these assumptions: it is seen as axiomatic that people make economic decisions while possessed of perfect information and perfect trust. Blessed with this information, we duly engage in the act of maximising our own expected utility.

This is doubly wrong. First of all, such conditions of perfect information do not exist. Secondly, even if you could create them, our brains have not evolved for such an environment; anyone in the past who tried to act in accordance with economic axioms of rationality would either die or (just as likely) be beaten to death by a cheering crowd.

There is a really important point to be made here. Since we do not have perfect information or trust, in considering a decision our evolved brains must consider not only the expected outcome of a decision, but also the possible variance in outcome. Unless you are starving, there is no point in climbing an extra 20ft up a tree to get three extra apples at a 5 per cent risk of death through a fall. ‘What’s the best I can do?’ thus plays second fiddle in the human brain to ‘What’s the worst that could happen?’ Once you understand this, the whole expected pattern of human behaviour changes — and differs from economic rationality a great deal. Once we understand this, we can design the world very differently for a very different and more realistic kind of brain.

Let’s take one great success from behavioural economics: the opt-out workplace pension. Considered from the point of view of utility maximising economic rationality, your decision to have a pension should be an entirely individual one, based on your perfect knowledge of the expected value of the pension. But in an uncertain world, people aren’t so much worried by the expected value of a pension as by the risk of being royally ripped off. If everyone in my company has the same pension, I may not notice if the charges go up — but all it takes is one sad bugger in the finance department to notice and we’ll all know. Having the same pension as all your colleagues feels inordinately safer, since you have 200 pairs of eyes, rather than one, keeping an eye on performance. This is, when you think about it, identical to the herding behaviour naturalists observe in okapi, eland, oryx, impala, duiker and hartebeest (sorry, I do a lot of cryptic crosswords and that antelope knowledge had to come in useful one day).

Is it irrational? No, in evolutionary terms it’s bloody clever. It’s also instinctive, not consciously rational. But it bears no relation to how economists think we should think.

The narrow view of human motivation in economics also poses huge creative limitations on problem-solving. (As the physicist Sir Christopher Llewellyn Smith remarked, ‘When I ask economists for suggestions, the answer always boils down to bribing people.’) But this narrow solution set also appeals to policy-makers because it allows them to be precisely wrong rather than vaguely right. And therefore fail conventionally rather than succeeding unconventionally which, as Keynes observed, was much better for the reputation.

How do we break this stranglehold? Well, if the problems have a root in evolutionary psychology, perhaps we should look there for the solution too. Trying to change people’s mind through refutation only entrenches their beliefs. Humour might just work. In a small Irish country town, I saw a glimmer of hope.

Comments