The Hepworth has been garnering plaudits right and left as a new museum to be welcomed to the fold, and my first visit to this monolithic structure with its feet in Wakefield’s River Calder exceeded all expectations. Designed by David Chipperfield Architects, the ten linked blocks that make up this new suite of galleries are spacious and light-filled with excellent views out to the river and town. Restaurant, education centre and offices are on the ground floor, and upstairs the art comes into its own.

At the top of the stairs is a room of six classic sculptures by Barbara Hepworth (1903–75), whose name the museum has taken since this significant figure of British Modernism was born in Wakefield. The six starring works include a couple of beautiful early figurative carvings (‘Kneeling Figure’, 1932, and ‘Mother and Child’, 1934), when Hepworth seems very close to Henry Moore in form and ambition, before she moved away into a more rigorous abstraction of resonating clarity (see ‘Two Forms with White [Greek]’, from 1963).

The subsequent galleries set Hepworth within the context of Modern British art, mixing sculptures and paintings to very good effect. There are many excellent things on display here, some from Wakefield’s permanent collection, others borrowed from the Arts Council, Tate or such distinguished private collections as that formed by the retired Leeds doctor Jeffrey Sherwin. Among the especially memorable are Robert Adam’s superb wood sculpture ‘Apocalyptic Figure’ (1951) and Prunella Clough’s ‘Paper Mill, Men and Paper Bales’ (1950). Outside, the frothing torrent of the Calder laps the walls. Inside, Gallery 4 is devoted to Hepworth at work, with a display of films, models, tools and workbench. Gallery 5 contains an amazing collection of Hepworth plasters, given to the museum by the artist’s family. This room alone is worth the trip, with its vast aluminium ‘Winged Figure’ at one end and aluminium ‘Construction (Crucifixion)’ punctuating the dramatic groupings of spectacular plaster forms.

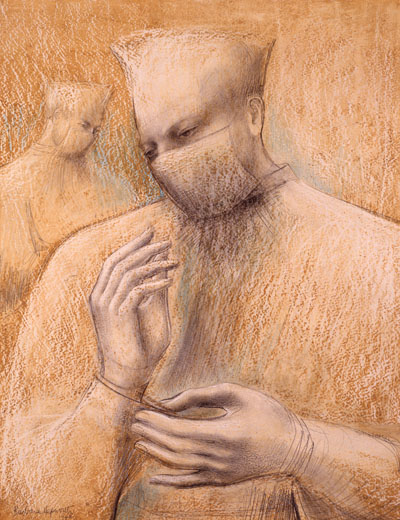

But the real reason for my visit was to see the exhibition of Hepworth’s Hospital drawings (until 3 February 2013). To get to this one passes through a gallery of St Ives art, including fine things by Roger Hilton, Patrick Heron and John Wells, and then enters a different atmosphere altogether. The Hospital ‘drawings’ are hybrid works, made with washes of oil colour on a pseudo-

gesso ground of roughly applied Ripolin paint, into which Hepworth has incised pencil marks. The resulting drawings of surgeons in the operating theatre are haunting: notice the way Hepworth focuses on eyes and hands in the figure groups which look remarkably like angels from Byzantine mosaics or Renaissance frescoes. Hepworth emphasises the creativity and skill of the surgeon rather than the suffering of the patient, and there is a hieratic quality to these scenes. She spoke of ‘the rare beauty of co-ordinated and harmonious unrehearsed movement which takes place…in the operating theatre’.

This is the first time so many of the Hospital drawings have been exhibited together, and they make a powerful, if not exactly joyful, impact. The exhibition is curated by Nathaniel Hepburn, director of Mascalls Gallery in Paddock Wood, Kent, to which the show will tour (14 June to 24 August 2013), after a pit stop at Pallant House in Chichester (16 February to 7 June). Hepburn also curated the Cedric Morris and Christopher Wood show at Norwich reviewed last week, and to have two such excellent exhibitions running concurrently, with well-written accompanying catalogues, is impressive indeed. As I was leaving The Hepworth, I saw a weasel hunting sinuously along the riverbank in the dusk, which was another bonus.

A very different kind of drawing exhibition is at the Redfern Gallery (Annabel Gault: New Work, 20 Cork Street, W1, until 24 January 2013). Annabel Gault (born 1952) is a powerfully expressive landscape painter who has focused her energies over the past two years on a series of large-scale drawings, which began in the Tresco Botanical Gardens, in the Scilly Isles. Gault had gone there in the winter intending to paint, but drew instead. Her first Tresco studies are in charcoal, and she captures with evocative line and massing the characteristic garden layout of palms and other rare plants.

As the drawings get bigger, they move into gouache (though still restricted to black and white), and the overall patterning emerges more strongly; the individual is gradually subsumed within the whole. The next subject was Gault’s own garden in Suffolk, which she drew all a-dapple in the hot spring of 2011. Now using ink, sometimes with wax resist, the interplay of moving foliage and strong light becomes ever more apparent. Another shift of medium, into graphite and mixed media, betokens a new fluidity of mark and heralds the most recent series of drawings, entitled simply ‘Foliage’. These are the most abstract, and while recognisably still derived from nature, are as much about the wider rhythms of nature’s flux and flow as they are about leaves in a breeze. It’s uplifting to see an artist drawing with ink so beautifully on such a scale.

Finally, an exhibition devoted to an underrated master: The Peculiarity of Algernon Newton at the Daniel Katz Gallery, 13 Old Bond Street, W1 (until 21 December). Grandson of the founder of Winsor & Newton and father of the actor Robert Newton, Algernon Newton (1880–1968) was a painter of town and country able to put a disturbing edge on the most seemingly prosaic subject. He was affectionately known as ‘Regent’s Canal-etto’ by contemporaries, because he painted the houses on London’s premier canal with a gorgeous 18th-century glow, and had obviously made a study of the Venetian’s methods. But there is nearly always an air of disquiet to his best pictures, an almost surrealist frisson behind the traditional glazes of his naturalistic approach. Not quite de Chirico, but a parallel with Hopper could be rewardingly explored. There’s a palpable mood of expectation in Newton’s images, mostly created by his ingenious control of light.

He was a superb painter of horses (he studied animal painting for three years) and trees, and his weather varies from the refulgent and benign to the downright minatory. When he was on the Regent’s Canal towpath he talked about seeing London ‘as it were from the wings in a theatre’, and there is certainly something of the stage set about his productions. Yet they are not cardboard cut-outs, merely dramatically lit and imbued with a sense of imminence. Andrew Graham-Dixon, in an ingenious catalogue essay, reads into these paintings Newton’s anguished response to the horrors of the first world war, and its decimation of a whole generation. ‘They are not topographical views but aftermaths,’ he writes, ‘and they are empty because a dreadful emptiness is their theme.’ I haven’t seen the show yet, but can’t believe that all of Newton’s paintings in this impressive selection are quite so bleak. Certainly worth a look to decide for yourself.

Comments