Lesley Blanch, who died in 2007 aged almost 103, did not want this book written. Having spent her whole life spinning a web of romantic tales around herself, the last thing she needed was a patient, dogged writer checking up on her, unpicking the fibs and the fantasies and unlocking the skeletons from their cupboards. Anne Boston, who admires her tricky subject and is well aware that fantasies can be as revealing as facts, nevertheless feels obliged, rightly in my view, to play the detective.

It was not until she was 50 that Blanch (born in 1904) published her first and instantly successful book, The Wilder Shores of Love, in which she described the romantic adventures of four European women in North Africa and the Middle East. By that time she had had a good few romantic adventures herself, and come a long way from the modest middle-class background in Chiswick where she grew up. She was a pretty, clever, wayward only child whose mother encouraged her in a passion for all things exotic and foreign, especially Russian.

In Journey into the Mind’s Eye, her outstandingly unreliable autobiography, published when she was 68, Blanch conjured up a Russian friend of her parents she called ‘The Traveller’, a mesmerising figure with a smooth bald head, slanted oriental eyes and a long sharp little finger nail, who enchanted her when she was a little girl, seduced her on a train when she was 17 and promised her marriage before abruptly vanishing when she was 21. Whether he ever existed outside her imagination is impossible, despite valiant efforts, for her biographer to tell, but it seems most likely that he was a composite figure, derived from Blanch’s youthful passion for the then fashionable Russian designers, dancers and writers and her affair with the powerful Russian-born director, Feodor Komisarjevsky, one of her early lovers. He was married eight times, including to Peggy Ashcroft, but eluded Blanch.

There is no doubt, though, that Blanch was a gifted writer and artist (largely self-taught, though she studied briefly at the Slade) with a driving need to move out of middle-class suburbia into a grander and more exotic milieu. She had some success, helping Komisarjevsky with theatre designs and writing for Vogue (‘My cook is a catastrophe’) before becoming the magazine’s features editor in the late 1930s. Her first marriage to an advertising agent did not last long; Boston suggests she loved his elegant Georgian house, which she managed to acquire for herself, more than she loved him. Somewhere along the way there was perhaps a child, father unknown, given up for adoption and untraceable. Her obsession with all things Slav persisted; and then in 1944 , in wartime London, still writing for Vogue (‘ The WAAF Way’) she took up with the man who seemed, for a while, to make all her dreams come true.

Romain Gary was a darkly handsome, heroic Free French airman ten years younger than Blanch, apparently from a grand Russian background and an aspiring writer. By the time it emerged that he was in fact from a modest Jewish family in Lithuania, he and Lesley were living together; they married in 1945, and after he found his way into the French diplomatic service embarked on some 15 years of travelling and working together.

Boston writes well, and perceptively, about this marriage of two mythomanes, both of whom feared stability and the mundane, drew a veil over unpalatable facts and were incapable of living by any rules but their own; it worked for a while, especially as they both took off as writers in the 1950s (his best-seller, The Roots of Heaven, came out in 1956). But Gary was a depressive, and also compulsively unfaithful; Blanch tolerated his moods and affairs until his romance with the young American actress Jean Seberg, the personification of a liberated younger generation, brought the dream to an ugly end in 1962.

But Blanch was both resilient and hardworking, and by this time her obsession with the dangerous and the exotic had led her to write her most substantial book, The Sabres of Paradise, the history of Imam Shamil, the warrior prophet who led the Caucasian rebels against Russia in the 19th century. According to Boston, she had admired him since childhood; certainly her assiduous reading and travelling in search of his traces show her at her most intrepid and determined. For all its colorful romanticism, the book broke new ground and is still admired today.

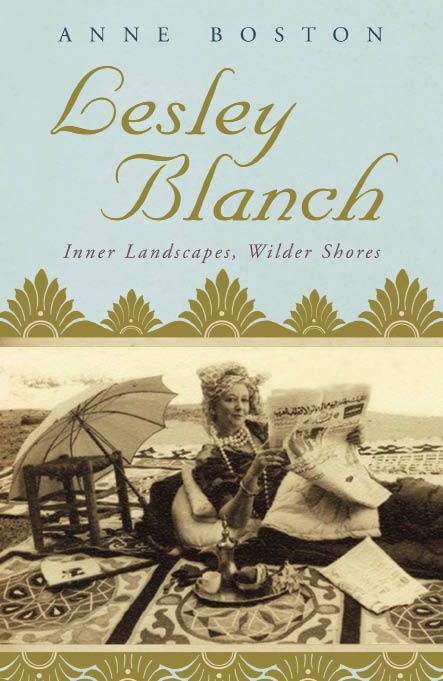

As she grew older, Blanch continued to write, living mostly in the South of France, travelling, cultivating diplomats and experts on Russian and Islamic culture, dressing à l’orientale, lounging on silken cushions and creating an exotic garden. Many journalists, including Boston, made the journey to visit her, especially as she turned 100 in 2007; most of them were too beguiled by the performance to question any of her stories.

Anne Boston has now looked more closely, and has written a scrupulous, sympathetic, occasionally rather flowery book which surely comes as close to the truth about an elusive and not altogether likeable subject as any biography could.

Smoking Ears and Screaming Teeth is written by Trevor Norton, not Trevor Nelson, as stated in 6th March issue. Apologies to the author.

Comments