Isaac Levido, the Tory election strategist who helped secure Boris Johnson’s landslide victory in 2019 and saved the Tories from oblivion in 2024, says (with the wisdom of grim experience) that ‘politicians are confidence players’. They perform best when their tails are up. In 2019 he had a candidate with his tail up who took the public with him. In 2024, in Rishi Sunak, he had a leader who had suffered a major crisis of confidence and projected a self-fulfilling air of doom.

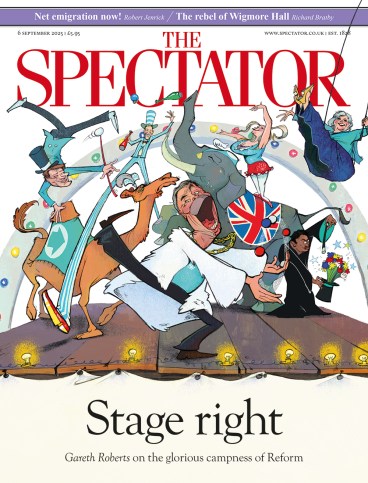

This eternal truth is likely to be reinforced on Saturday when Nigel Farage takes to the stage in Birmingham for the first party conference speech he has given as a potential prime minister. A year ago, when he last addressed his supporters, the poll of polls which is closely monitored in Reform UK HQ had the party on 19 per cent, Labour on 32 per cent and the Tories on 22 per cent. Now Reform is on 31 per cent, nine points ahead of Labour and 14 points clear of the Tories. A result like that in 2029 would deliver a Reform majority.

In Reform’s office the buzz phrase is: ‘We didn’t come this far only to come this far.’ The party has the two attributes money can’t buy in politics: momentum and optimism.

On the other end of the confidence equation is Keir Starmer, who this week reshuffled his No. 10 team in a brutal but somehow indecisive fashion. He sacked his communications chief, two policy chiefs and his head of delivery. As Jeremy Thorpe observed of Harold Macmillan after the Night of the Long Knives of 1962: ‘Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his friends for his life’ – or, in Starmer’s case, his aides.

It appeared like a move governed by anxiety about Farage gaining the votes of people who have not seen the changes Starmer promised. But shifting the deckchairs while hoping the iceberg melts is unlikely to change their views of Starmer. ‘He habitually blames staff for his own lack of direction and clarity,’ says one SW1 veteran. ‘He’s like a passive-aggressive Gordon Brown.’ The rationale, one of his close aides admits, is this: ‘One of our biggest weaknesses in terms of perceptions of the government is the gap between what Keir says and what the government does. We needed a stronger command centre.’

Work on the plan began in the spring, prior to the local elections, when Morgan McSweeney, the chief of staff, and his two deputies, Vidhya Alakeson and Jill Cuthbertson, discussed why the government was not delivering. There was pressure on Starmer from Tony Blair and Gordon Brown to beef up his operation and input from serial government troubleshooter Louise Casey and former cabinet secretary Gus O’Donnell.

Reform has two attributes money can’t buy in politics: momentum and optimism

Where there were three heads of policy – Stuart Ingham, Olaf Bell and Liz Lloyd – there is now one: Alakeson herself, who was the principal architect of the changes. But she is also deputy chief of staff and has oversight of ‘delivery’. Insiders predict she will have to hire a new deputy to keep all the balls in the air. Ingham, Starmer’s longest-serving aide, has moved sideways to become a ‘senior counsellor’ to the PM.

Where once there were two communications directors there are now three. David Dinsmore has become civil service head of comms, alongside Tim Allan, a former Blair aide and PR man, as head of strategic communications, and Steph Driver, who remains. McSweeney met Allan earlier in the year to discuss the role which eventually went to Dinsmore but has told colleagues he concluded he could have both.

Perhaps the most significant move was to bring in Darren Jones, the chief secretary to the Treasury, as ‘chief secretary to the prime minister’, adding political heft to drive Whitehall. It was also an admission that the cabinet secretary Chris Wormald is at best ineffectual and at worst a blockage to change. Jones is talented and a good communicator but, as one colleague observes, ‘It is interesting to give the job to one of the ministers who is least popular with the rest of the cabinet.’

One of those who wanted to see a clearer chain of command says the changes resembled ‘a camel designed by a committee trying to draw a horse’, adding: ‘For a Prime Minister with a reputation for ruthlessness, these are decidedly unruthless decisions. Let’s defang people but not fire them. Let’s have multiple heads of a hydra instead of making a decision about whose vision wins.’

With Farage ahead, McSweeney has made it clear that the top priority for the autumn is ‘moving further and faster’ on curbing small boat arrivals and getting asylum seekers out of hotels. ‘I think it is clear that the political patience has gone in the country.’ Labour’s hope is that the growing scrutiny of Reform’s policies will ‘expose the emptiness of what they are offering’.

It will only boost morale in Reform to know how they have spooked the government. After securing 22 national newspaper front pages in six weeks over the summer, their conference slogan is ‘The Next Step’. Aides are working until 3 a.m. each night this week to prepare. ‘The key is to present ourselves as a party that could form the next government while also retaining that edge that makes us different,’ says one.

Farage’s opponents make two assumptions about his speech: he will use it to say more about what he stands for, rather than what he is against, and give voters an idea of what he thinks about schools and the NHS, as well as his core subjects of immigration and crime. But as a Reform official observes: ‘I don’t think we can make any assumptions about Nigel’s speech… Nigel’s speech is somewhere in the back of Nigel’s head.’

Instead, the big plan is to show that Reform is not just the Farage show. Reform’s two mayors – Andrea Jenkyns and Luke Campbell – will appear, along with the 19-year-old Warwickshire council leader George Finch, Sarah Pochin, the party’s first female MP, and a recent recruit, the councillor Laila Cunningham. Insiders also point to Derbyshire councillor Charlotte Hill, 25, who joined Ukip when she was 14 and is now in charge of transport policy. A former engineer with National Highways, Hill was also a beauty queen who was Derbyshire’s entrant in Miss Great Britain and Miss Universe Great Britain. ‘She’s a bit glam but she’s also the cabinet member for potholes,’ an admiring colleague notes. ‘In the past, Farage-led political parties have struggled to have young, interesting people coming through. It’s a sign of a healthy ecosystem to have young, good-looking, vibrant people.’ Confidence players indeed.

Comments