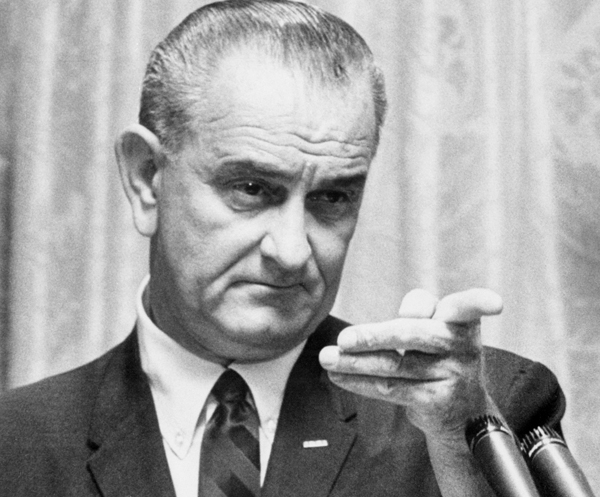

Just after 8.50 on Tuesday morning, 26 November 1963, Lyndon Baines Johnson sat down behind the desk in the Oval Office for the first time as President, four days after the assassination of John F. Kennedy. According to Robert Caro, the new chief executive of the United States, now the most powerful person in the world, did not then make a call to his Soviet counterpart Nikita Khrushchev; nor did he confer with aides, or have his secretary place calls to the leaders of Congress, or issue an executive order. Instead, Johnson’s initial action was to phone, himself, the offices of the US Senate and order the desk he used as Senate Majority Leader to be delivered to the White House to replace the government-issue model installed the night before.

This was not merely an obsessive, self-absorbed act by a neurotic and insecure man, although LBJ was deeply neurotic and insecure. Commandeering his old desk signified two things: first, that Johnson would no longer live in the shadow of the hated and envied royal family called Kennedy — that he would not settle for the role of constitutionally dictated placeholder for the fallen king — and second, that he would henceforth run the government in the direct, hands-on manner that he ran the Senate from 1954 to 1960, ‘as if it were an obedient orchestra’. According to Caro, legislation that had languished while Kennedy tended to his own image, or because he too easily conceded defeat, would pass because Lyndon Johnson willed it to pass. The one-time ‘Master of the Senate’ would now master all of Washington and the country, if not the world.

Such details are what make The Passage of Power, the fourth volume in Caro’s The Years of Lyndon Johnson, such a great and occasionally astonishing biography. His accumulation of original material — through interviews, and his voracious reading of already published work, oral histories and presidential papers — leaves all competitors in the dust. It’s as if Caro has taken his subject’s political mantra directly to heart: ‘If we do everything, we will win.’ For Caro, if you interview everybody, and read everything, you will write great history. (There is one notable exception, Johnson’s longtime aide, Bill Moyers, who refused Caro an interview).

The comparison goes only so far, however, since LBJ often cheated to win. Stealing elections was a habit of his going back to college, and we owe Caro for the great historical scoop in his second volume, Means of Ascent: that Johnson won his first US Senate race in 1948 through fraud. The evidence gathered by Caro points to another stolen election in 1960, when LBJ was Kennedy’s Vice Presidential running mate: voter theft in Texas evidently contributed to Kennedy’s narrow win over Richard Nixon, though Caro is careful not to claim definitive proof. But it’s important to know that if LBJ’s 24 home-state electoral votes were added to the 27 electoral votes in Illinois likely stolen by the Chicago Democratic machine, Nixon would have won with 270 electoral votes to 252 for Kennedy.

There are other important corrections of the historical record in this volume. For example, Caro demolishes the party line advanced by Kennedy’s acolytes that their hero never intended to drop Johnson from the ticket in 1964. More likely, as Caro persuasively argues, LBJ had served Kennedy’s purpose by recovering the formerly ‘solid South’ for the Democrats in 1960 (with votes obtained honestly and courageously), but that with black civil rights emerging as the great issue of the day, the President from liberal Massachusetts needed a liberal southerner like North Carolina’s Terry Sanford to keep up with the times.

As useful and important as Caro’s journalistic accomplishments are, none of them will distract readers from the more compelling story of Johnson’s bitter rivalry with the Kennedy brothers, especially Robert Kennedy, who despised Johnson. Caro tells us that Johnson, having badly misread John Kennedy as nothing more than a lazy, rich ‘playboy’ — and meanwhile paralysed by his own profound fear of defeat — frittered away his chances to secure the Democratic presidential nomination in 1960 while Kennedy scoured the country for convention delegates. ‘I was meant to be President,’ Johnson would say, but when he realised, too late, that Kennedy would win on the first ballot in Los Angeles, the poor boy who became a protégé of Franklin D. Roosevelt and then a master politician in his own right, fell into despair as his lifelong ambition disappeared in a cloud bank over Camelot.

Johnson’s willingness to accept the vice presidency (Robert Kennedy’s apparently unauthorised opposition to his brother’s selection of LBJ is another Caro scoop) is testimony either to Johnson’s political acumen — vice presidents, he realised, became president far more often than senators — or his utter dejection. In any event, the next three years were a time of miserable isolation created by the Kennedy in-crowd — ended only by an assassin’s bullet that for a time must have weighed heavily on Johnson’s conscience. With an ego larger than Texas itself, how could he not have wished secretly for his younger rival’s untimely demise?

The Kennedys and their courtiers knew this about Johnson, despite all his brave talk of ‘continuity’. LBJ’s determined restraint — his Uriah Heepish humility — was quickly overwhelmed by the real Johnson, a man of almost unbelievable energy, political talent and arrogance. Caro is peerless when he narrates LBJ’s tactically brilliant campaign to push through Kennedy’s civil rights bill — stalled interminably by LBJ’s longtime allies in the Southern Democratic caucus. (He crucially understood that he first needed to pass Kennedy’s proposed tax cut.)

Here, Caro wants us to know, was the best of Lyndon Johnson. As President, the bullying liar of Caro’s previous volumes becomes, suddenly, a leader and statesman of great stature. Caro makes clear that Johnson’s motives weren’t pure: he pushed hard for passage of the civil rights bill in order to nullify liberals who might have rallied around a Robert Kennedy candidacy at the nominating convention in August 1964. But whatever ultimately moved or frightened him, Caro writes, ‘When the office was suddenly thrust on him … when there was suddenly no longer room for doubts or hesitation, when he had to act — he acted.’

Anyone familiar with LBJ’s disastrous second term in office will understand Caro’s and his publisher’s decision to end the narrative on 2 July 1964, with Johnson’s signing of the Civil Rights Act — really the high point of his political career. The war in Vietnam ruined the 36th President’s reputation and Caro faces his most difficult task in describing the next four and a half years of the Johnson presidency. Even greater feats of social legislation, including Medicare, are yet to come, but as Caro writes near the end of the book, the legacy (though shared with Richard Nixon) of 58,000 dead and 300,000 wounded Americans, and possibly more than two million Vietnamese casualties — ‘the amputations, the blindness, the terrible scars of body and mind’ — will make it hard to remember the LBJ who temporarily soared beyond his predilection for destruction and mendacity.

Because Caro is a non-PhD historian who started out as a reporter, his entire Johnson project is an audacious proposition, for he has never totally overcome the condescension of the academy. With this book, however, he deserves a place in the same arena as America’s greatest journalist-turned-professional historian, Allan Nevins, who also did not possess a doctorate but whose u nsurpassable eight-volume Ordeal of the Union — which covers the run up to the Civil War and the war itself — bears comparison with The Years of Lyndon Johnson. Nevins’s scope and perspective are broader, his sweep more majestic, but then Nevins wasn’t constrained by having to interview, say, living members of Lincoln’s cabinet who might later challenge his account of the war.

In fact, Caro’s deep primary research should be the envy of academic historians. Nevertheless, this technique has pitfalls. So many direct quotations slow down his narrative, which at times turns repetitive. The weakness in the book is that Caro stays so close to his subject that he sometimes seems to suffer from the same tunnel vision that drives the politicians he describes. One wishes he would occasionally halt his breathless telling of the story to bring news from outside the bubble of presidential power and ambition, or introduce us to someone kinder and more principled than the

John F. Kennedy who, according to George W. Ball, threatened Adlai Stevenson during the 1960 campaign. Quoting Stevenson, Ball recounts:

Kennedy behaved just like his old man. He said to me, ‘Look, I have the votes for the nomination and if you don’t give me your support, I’ll have to shit all over you.’

This is not in the book, but I’m sure

Robert Caro knows it by heart.

Comments