It’s a palace drama with all the trimmings. Trevor Nunn’s new production, The Lion in Winter, plunges us into the court of Henry II and his spurned wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, as they struggle to decide which of their three sons should inherit the throne. Eleanor, held prisoner in a deluxe royal fortress, has been granted leave to join the family at Christmas. ‘Thanks for letting me out,’ she says, on their first meeting. ‘It’s only for the holidays,’ jokes Henry. Clearly a king who locks his wife in the broom cupboard won’t pay much heed to her views on the succession. So there’s an emotional and dramatic illogicality here right from the start. And, right from the start, the playwright couldn’t give a stuff. Which helps.

The script is an unashamed slice of historical knockabout aimed well below Bernard Shaw level and a few notches above Carry On. ‘He’s got a knife!’ yells a princelet when a blade is pulled. ‘Of course he’s got a knife,’ soothes his mother. ‘We’ve all got knives. It’s 1183.’ Some things are done superbly, some atrociously. Set and costumes look great. The well-scrubbed castle is a magnificent arrangement of vaulted arches, receding in cleverly mendacious perspective, which gives the impression of boundless space. Brilliant stuff. And the drapes are exquisite. An odd thing to say about drapes but these are lush and lovely acres of cloth, hung from a dominant position, and gathered to create shadowy ripples of descending parabolas. Truly magical.

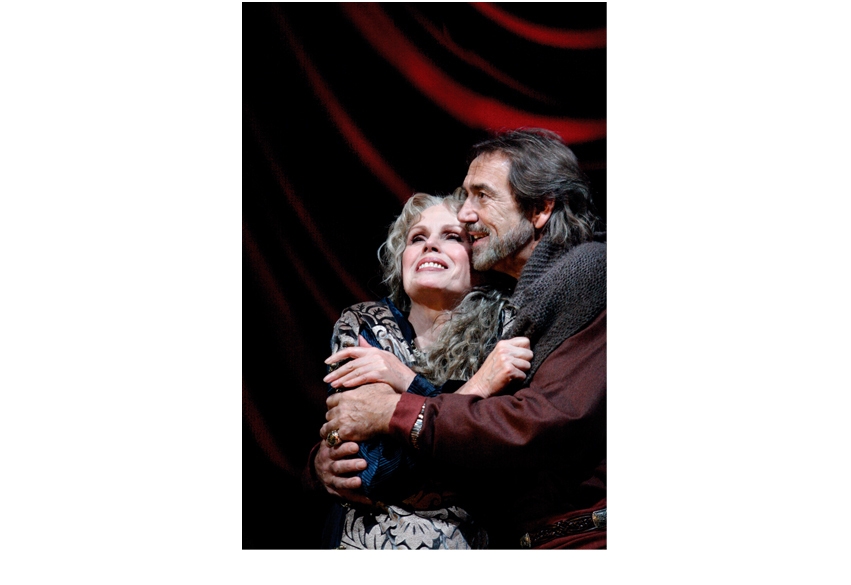

If only Sir Trev had paid more attention during the auditions. The three princes are seriously bad. John is a shouty, annoying little prat. Richard is a shouty, annoying big prat. And Geoffrey is bit of both and a bit of neither. Sighs of gratitude surge forth whenever the bickering trio withdraw, and the stars take centre stage. Joanna Lumley does a cracking turn as Eleanor. Melancholy, languid, spikily intelligent and often very funny, she fits brilliantly into the slender groove where the play resides. She’s matched for starry charisma by Robert Lindsay as Henry.

Lindsay is a trickster type, a cynical outsider who excels at playing subversive smart alecs. Majesty isn’t his natural register and although he can suggest authority, by flexing his vocal amplifier and frowning aggressively, he does it like a Community Patrol Officer. His heart’s somewhere else. And when he aims for emotional turmoil he produces a textbook display, as in, ‘here’s what the textbook says.’ His voice cracks, his shoulders droop, his sprightly movements seize up with nonagenarian silt. Profound superficiality is the result.

But when he delivers a frisky one-liner he’s unbeatable. The King of France pours him a glass of the newfangled ‘burnt wine’ or brandy. Henry (unimpressed): ‘The Irish have been boiling that stuff since before the snakes left.’ Lumley and Lindsay sparkle together enjoyably enough but the sexual chemistry between them is at the sub-atomic level. (The script’s fault, again.) In the closing scene Henry moves in for a chaste clinch with his banged-up former bride. And though he chafes her flanks enthusiastically he merely looks like a Liverpool fan celebrating a goal with a stranger.

Rumour has it that the show hasn’t quite sparked a riot at the box office. Having missed press night, I bought a ten-quid perch up in the gods and, thanks to spare capacity, I was shown to a cosier berth in the Royal Circle priced at £47.50. If someone kills you to get your ticket, they’re just making excuses.

The Donmar’s West End season continues at the teeny Trafalgar Studio 2. Salt, Root and Roe by Tim Price takes us into the twilight zone of Alzheimer’s. One old biddy has lost her marbles. And her kindly sister and her even kindlier niece are helping her cope. Which is sweet. And bloody tedious. As always with amnesia plays, it’s hard to care for a character with no character. A goldfish is a goldfish even if it happens to inhabit human remains.

Poor Imogen Stubbs struggles gamely to invest the niece with some weight and energy, but both the script, and Hamish Pirie’s scruffy, confused production, are determined to defeat her. The playwright doesn’t even trouble to name the Welsh seaside town where the inaction is located. The play opens with a motionless and puzzling scene between two characters on a park bench. It later transpires that they’re indoors. A park bench to signal a sitting room? How come? Because no one cared. No one bothered to check that this play honoured the high and hard-won renown of the Donmar. Metro Goldwyn Meyer was once the greatest film studio in the world. Today it runs a few gambling joints in Las Vegas. Donmar beware.

Comments