It’s kind of surreal being here.’ The general sentiment, no doubt, of most people on planet Earth right now, but the specific words of Matt Damon at the world première of his latest film earlier this year. The reason for his befuddlement? The film was The Great Wall, for which he had moved to China for half a year with his family. But the première was taking place beneath the extravagant pagoda of Grauman’s Chinese Theatre on Hollywood Boulevard. From actual China to Los Angeles’ idea of China — no wonder Damon found it weird.

Yet, as so often happens in Hollywood, the weird could well become the way of things. The Great Wall and its première are the result of what is becoming one of the most significant partnerships in show business, between the American and the Chinese film industries. Other actors will have to make the 6,500-mile journey between LA and Shanghai.

Strangely, this is a partnership founded on mistrust. For years, China’s communist regime took a dim view of the luminous art form of cinema. The only movies that it really tolerated were works of propaganda, and there was certainly no room for anything from the capitalist, consumerist US of A. Which might have worked, had it not been for the fact that no one wanted to pay to see propaganda. In 1994, to support ailing theatres, the state agreed a revenue-sharing deal to import The Fugitive — the first time Hollywood had been let into the Chinese market for 45 years. The film made what, at that time and in that place, was an impressive $3 million, but it also set a precedent. Nowadays, after a landmark 2012 deal signed by vice-president Joe Biden and premier Xi Jinping, and urged on by the dictates of the World Trade Organisation, China imports 34 foreign films a year through similar deals. With the quota set to double, American filmmakers are sensing an opportunity.

America’s fascination with China can be traced from the earliest days of cinema through to D.W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms (1919), with its sympathetic portrayal of a Chinese man in love with a London girl, through to Boris Karloff in thick make-up for The Mask of Fu Manchu (1932), and on to the casting of martial artists like Jet Li in movies such as Romeo Must Die (2000). But now the country has an even greater allure: a billion potential ticket sales.

What wouldn’t a Hollywood producer do for that sort of box office? Very little, it turns out. A special cut of Iron Man 3 (2013) was prepared for China, featuring extra scenes with popular Chinese actors, along with a super-villainous amount of product placement for the milk brand Yili. Then the makers of Transformers: Age of Extinction (2014) went even further by setting and shooting a large part of their movie in China, with appearances from several Chinese stars and several hundred Chinese products. The idea was, in part, to blur the line between what counts as an American film and what counts as a Chinese one — so that the quota needn’t matter.

However grim these methods are, they appear to be working. Transformers: Age of Extinction overcame its monumental awfulness to become the record grossing film in China at the time, although it has since been beaten by three others, including Furious 7 (2015). The promise of even more money has led all the major studios to strengthen their ties with the Chinese film industry, from the state bureaucracy downwards.

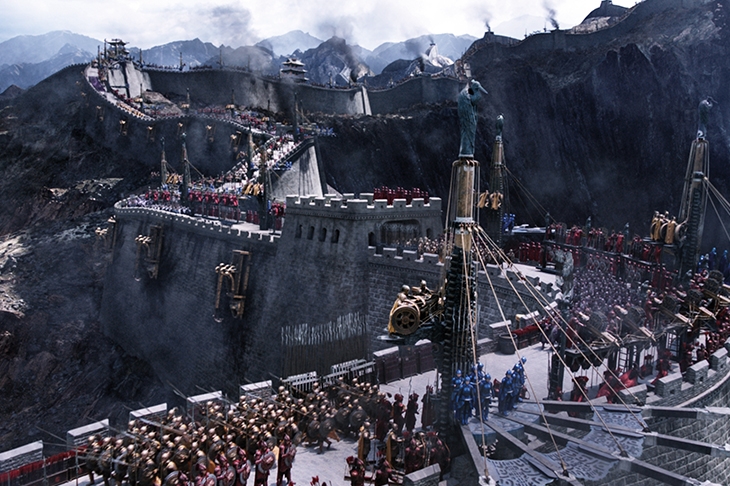

Which brings us back to the special case of The Great Wall. Early in its development, about six years ago, this film seemed as though it was going down the Transformers route. Its impetus came from Hollywood: the production company was Legendary East, a Hong Kong offshoot of the American media firm Legendary Entertainment. Its story was geared for China: the Great Wall, Song dynasty soldiers, monsters, yadda yadda yadda.

Then something happened. Legendary Entertainment was bought for $3.5 billion by China’s Wanda Group. And, with that transaction, the nature of The Great Wall changed. Its production was still to be a very modern mix of Chinese and American resources, but it suddenly became a cultural export instead of a cultural import. One of China’s most fêted filmmakers — Zhang Yimou, the man behind Hero (2002) and the opening ceremony of the Beijing Olympics — was signed up to direct it. Matt Damon was brought on board, one assumes, as a face with international appeal.

There are, however, doubts about how international this appeal has proved to be. The Great Wall (China’s most expensive film to date) has already recouped its $150 million budget in Chinese cinemas, but it’s struggling to do anything much in America. The whole project has been dragged down by bad reviews and worse accusations. A thousand opinion pieces have beenwritten about whether it’s right to cast Damon as the heroic lead in a film set in medieval China.

And racial politics aren’t the only politics thrown up by this new era of movie-making. An ongoing partnership between the American and Chinese film industries could be the means, or at least part of the means, towards friendlier relations between the two countries. Or it could just devolve into a new battleground. During his presidential campaign, Donald Trump called, as both Republican and Democratic lawmakers had before him, for more scrutiny of China’s takeover deals of Hollywood companies. For his part, the chairman of Wanda Group, Wang Jianlin, has warned that any restrictions could threaten the jobs of over 20,000 Americans.

Above it all hangs the question of whether the two film industries are cooperating for mutual gain or for competitive advantage. Last year, Chinese box-office takings ($6.6 billion) were second only — albeit by some distance — to America’s ($11.4 billion). Is Hollywood piggybacking on China to maintain its privileged ranking? Or is China piggybacking on Hollywood in order to surpass it? The implications in either case are not just financial. Cinema, even when it’s not twisted into propaganda, is a medium through which people see the world. What will we see through it in the decades to come?

The film business is globalising in ways that not only Matt Damon will find confusing. Had I been there with him at The Great Wall première in February, I would have pointed out that Grauman’s Chinese Theatre isn’t actually called Grauman’s Chinese Theatre these days. It’s now officially the TCL Chinese Theatre, after the naming rights were sold to China’s TCL Corporation in 2013. Perhaps he’d have found it reassuring to know that, although he wasn’t in China any more, China was still there with him.

Comments