Few modern politicians can claim to have changed their country, and fewer still can claim to have saved it. One who can is the late Alistair Darling.

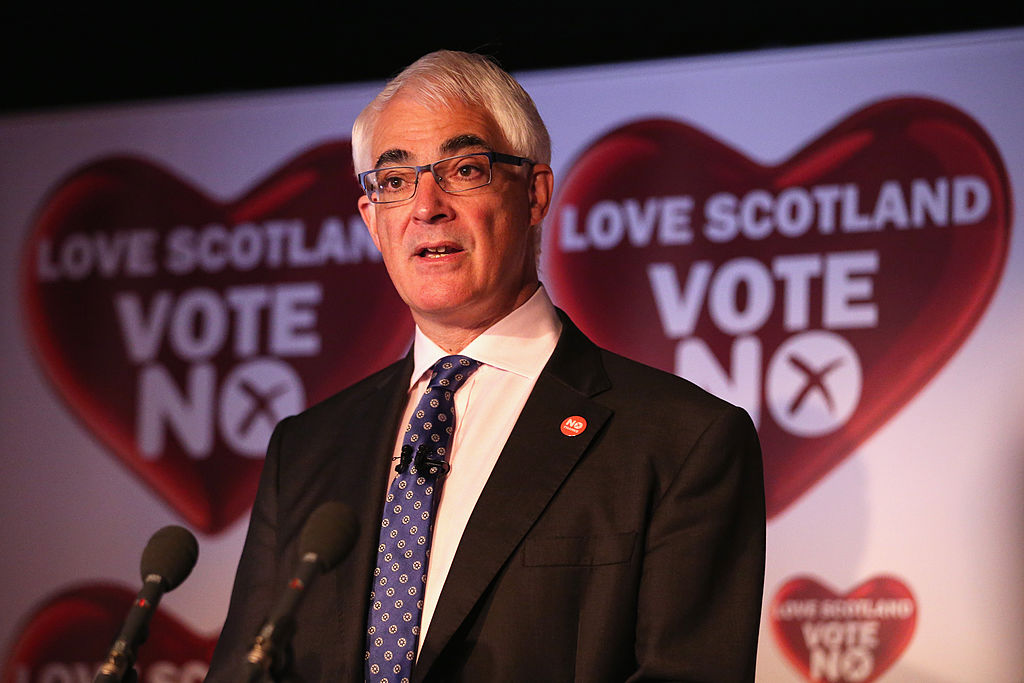

This is not a reference to his role as Chancellor of the Exchequer during the 2008/09 global financial crisis, but rather his role as the political leader of the Better Together campaign during the 2014 Scottish independence referendum. With a relentless focus on the economic risks of independence, it was Darling, perhaps more than anyone else, who shaped the arguments that would, ultimately, keep the United Kingdom together.

Of course, Darling’s opposition to Scottish independence was multifaceted. Like all his politics, it came from his deep-rooted belief that collective action was the only solution to the social injustice he so passionately opposed. Indeed, he firmly believed, in the words of the Labour Party membership card he would carry for five decades, that it was ‘by the strength of our common endeavour that we achieve more than we achieve alone’.

As someone with a keen appreciation of history, Darling understood that whatever the SNP tried to claim, nationalism was inherently divisive and exclusionary.

This meant he was not – as some of his separatist critics would try to brand him – a mere British nationalist, a different side to the SNP’s grubby coin. Rather, he was someone who resolutely believed in the pooling and sharing of resources in order to tackle shared challenges.

But Darling was also not naïve about the dangers of nationalism, either. As someone with a keen appreciation of history, he understood that whatever the SNP tried to claim, nationalism was inherently divisive and exclusionary. This occasionally led him into controversy – he once criticised Salmond’s version of civic nationalism by comparing the SNP leader to the North Korean despot Kim Jong-il – but rarely misjudgement.

Finally, it was Darling’s grounding in real world politics, and particularly his commitment to honest debate, that made him a champion of the anti-nationalist cause. Having done the job himself – not least as Chancellor during those dark days of the financial crisis – he was instinctively sceptical of Salmond and the Yes campaign’s more outlandish and fanciful claims. Darling, in short, was a man who valued facts over flags.

All of this made him a formidable campaign head, even if he occasionally lacked the charisma and raw magnetism that accompanied Salmond. But even this Darling slowly turned to his advantage, contrasting his natural caution, credibility and experience with Salmond’s enticing but reckless bravado. During a televised debate between the pair, Darling’s challenge to Salmond over his lack of a ‘Plan B’ on a post-independence currency union left the SNP leader looking like an ill-prepared chancer. It would prove a pivotal moment in the campaign, and also Darling’s finest.

Yet, perhaps even more importantly than his high-profile appearances, it was Darling’s shaping of the Better Together message – and particularly his focus on the economic risks of separation – that was most impactful. Of course, it is Gordon Brown who is best remembered for making the case for the ‘social Union’ with his barnstorming intervention in the final days of the campaign, and this undoubtedly helped win over Labour voters contemplating backing a Yes vote.

But it was Darling who ultimately understood that the Union would be won and lost on the financial and economic arguments, and helped honed the Better Together image in that vein. As a result, his opponents would brand his campaign ‘Project Fear’, but the collapse of the oil price post-referendum shows that, if anything, Darling was too reserved when articulating the economic risks of independence. At the same time, he won the respect of Better Together staff by sticking to his guns, trusting his instincts, and rebutting panicked – and generally needless – criticism of the campaign that emerged from almost every quarter in the run up to the independence vote.

Of course, as an MP for almost 30 years, and a cabinet minister for many of those, 2014 is just one moment in a long, varied, and colourful political career. But it is perhaps the most significant one. Today, those in Scotland who share Darling’s belief in the strength of the common endeavour, will not only mourn his passing, but will continue to owe him an enormous and lasting debt.

Comments