Despite its prestige, Vienna can seem parochial. This is as true today as it was during its turn-of-the-century golden age, when it incubated a generous welfare state – that is still with us – and all those Austro-Hungarian Empire weirdos: glowering hypnotist astrologers in full metal evening dress, hysterical socialites howling at the help from threadbare chaises-longues, fiendish necromancers summoning racial purity in front of frothing cauldrons of goulash.

Before 1938, Vienna also had a cosmopolitan intellectual culture. Its notables, often – but not all – Jewish, included Freud and Wittgenstein, radical figures in their own fields who became well-known beyond them. Arnold Schoenberg, the ‘emancipator of dissonance’ in music, is another, but his legacy is more ambiguous. Although Vienna has been celebrating his 150th birthday all year (it was hard to miss all the posters advertising events), there’s a dissonance between who Schoenberg was, how his ideas and music were received then and since, and how the city of his birth remembers him now.

Schoenberg simply isn’t fun or popular enough to be part of the Viennese cultural-heritage-industrial complex, the imaginary but pervasive body tasked with keeping the city’s beloved legacy figures (Mozart, Beethoven, Klimt, Freud) in gleaming sarcophagi with glossy multilingual brochures for the tourists. His personality was too dissonant for that. Schoenberg, after all, brought modernist art and mid-century popular culture into unison without harmonising them.

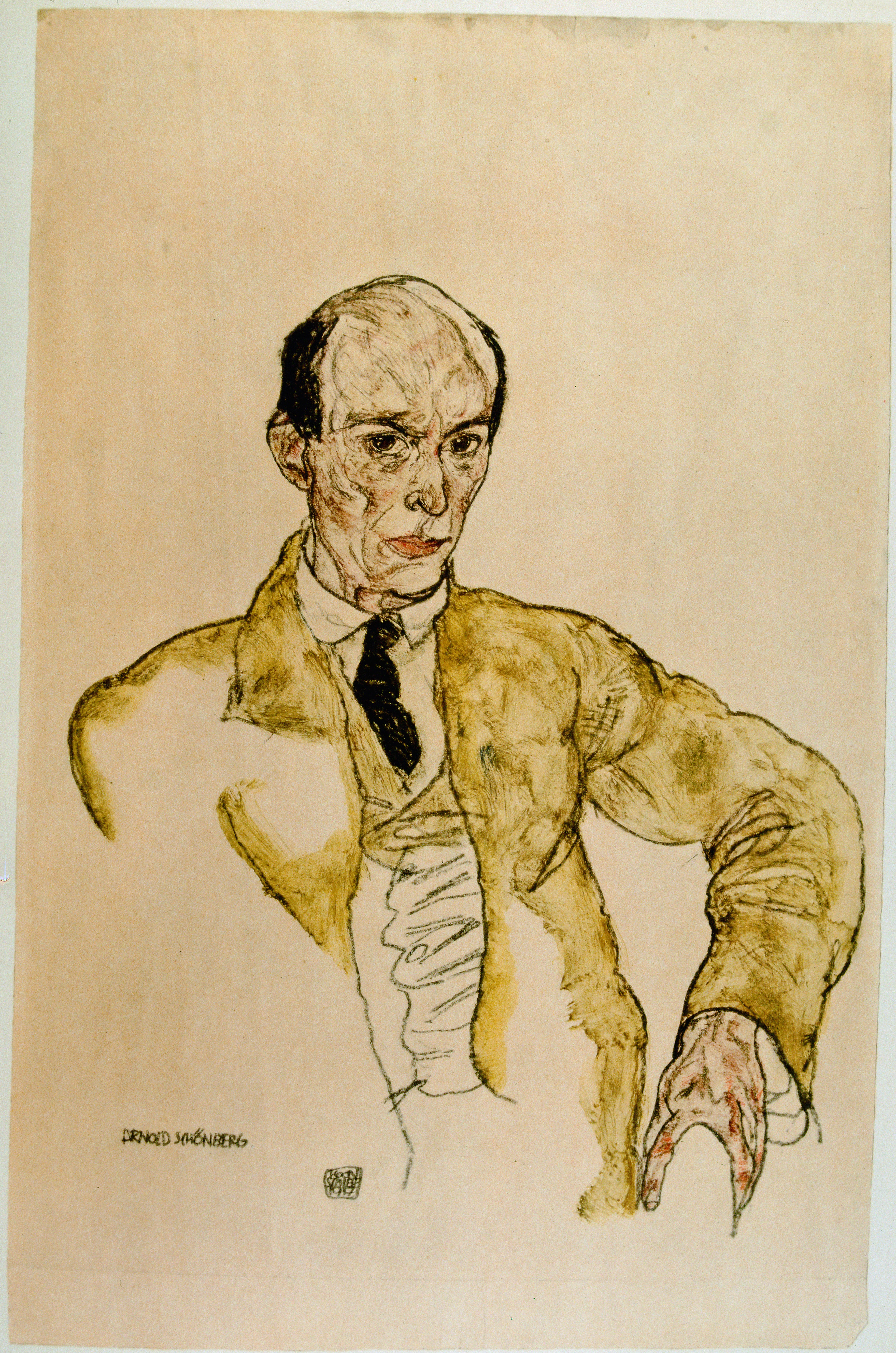

A grumpy avant-gardist with monarchist sympathies who had his portrait done by Schiele and Man Ray; a Protestant convert (obliged to become Lutheran to enter Vienna high society) who returned to Judaism in a Paris synagogue with the help of Albert Einstein and Marc Chagall; a teacher of Edgard Varèse, Harpo Marx, and Peter Lorre, who eventually became a lover of westerns, but whose ideas form the basis for Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus.

Schoenberg remains, however, a byword for difficulty. We expect, and are told to fear his gnarly, shrill works and his theories about how their difficulty proves their value. His admirers rightly maintain that its rewards come only after you’ve broken through an initial discomfort barrier, but Schoenberg’s reputation still precedes him enough for venues and concert organisers to shy away from putting on much beyond his easier earlier work like Verklärte Nacht.

The piece is – unsurprisingly – at the centre of many of the ‘Schoenberg 150’ concerts that have sprung up around the world. The rest of his output: not so much. There is no relation between Schoenberg’s reputation and how much his music has ever been performed. It’s still quite right, though, that things centre on the dozens of concerts, talks, and exhibitions in the Austrian capital.

These culminated in the compelling birthday performance of the symphonic cantata Gurre-Lieder in the magnificent Golden Hall of the Musikverein. Other events, such as the Diotima Quartet’s performance of String Quartet No.1, and the exhibition Listening to Love with Arnold Schoenberg, both at the Arnold Schoenberg Centre, were, however, the opposite of the birthday concert in feel and tone. It turns out that events about, among other things, the emancipation of dissonance were themselves examples of emotional if not auditory dissonance.

The birthday concert was unrelenting grand; the performance at the Centre, far more intimate. In the Musikverein foyer, Vienna’s cultural dignitaries waved and nodded and bowed to each other, hailing crumpled professors and retired conductors, half-smiling at hated rivals. At the Centre, we were presented with a cuddlier version of Schoenberg.

Under new director Ulrike Anton, the Centre focuses on outreach and accessibility, emphasising how to listen to Schoenberg’s music but downplaying his radical, highly technical, innovations, such as the twelve-tone technique. The Centre is welcomingly unflashy, dignified in how it hasn’t and won’t try to turn Schoenberg into a literal chocolate like Mozart or a finger puppet like Freud. What we get is dissonant modernism with a human face.

Listening to Love with Arnold Schoenberg, meanwhile, stresses how love – a relatable concept – appears prominently in the life and work of this unrelatable figure. Handwritten scores, drafts, and diagrams relating to Verklärte Nacht and the opera Moses und Aron are delicately propped up in cabinets under dim lighting, while examples of the composer’s paintings (self-portraits, stage designs) line the walls, complemented by photographs of the composer at his holiday home at Lake Traunsee near Salzburg with his first wife Mathilde, and a sepia photograph of his wedding to second wife Gertrude in Venice.

It’s a thought-provoking, but hardly exciting take on the man behind the difficult music. There’s little for anyone not already interested. It does, however, attest to the value of small and gentle – and provincial and specialist – museums. British institutions should take note that not everything has to be block-rockingly intersectional.

Listening to Love does, however, sharpen the dissonance between the birthday concert and the string quartet. Gurre-Lieder is, after all, a genre piece: a supernatural melodrama that many audiences and musicians – including those at the Musikverein – will likely mistake as straight romanticism, missing how Schoenberg parodies these conventions. String Quartet No.1 is far more straightforward, even if Schoenberg stretches the form further than any composer before him. The Diotima Quartet keep it that way – thoughtful, unironic, unpedantic.

Gurre-Lieder is, essentially, a doomed zombie romance story. The score and libretto are Wagnerian in their hugeness. As is the venue in which we witness it performed. The Golden Hall is an obscenely lustrous secular temple to music. There’s no dress code these days, but I witness much delirious elegance nonetheless – shimmering gowns; smiles embossed on anti-gravitational facelifts; blinding squeaks emitted by patent leather shufflers. The pinstriped gentleman at the end of my row looks like the biologically unviable lovechild of Henry Kissinger and Leo Strauss, still purplish from a summer up at some massive lake house, diligently following his own copy of the score throughout, never once looking up.

Schoenberg’s First String Quartet is neither more nor less demanding than Gurre-Lieder. It just requires a different type of concentration. Gurre-Lieder needs massive forces: five solo singers, a 150-piece orchestra, and a mixed choir of 200 performing over two and a half hours; the First String Quartet is one densely worked out movement, lasting 45 minutes or so. The space in which we hear it is very different: sleekly minimal, unglitzy, the audience one-tenth of the size of the Golden Hall. Nor were they the same people: this was a tuxedo-free zone with an engaged, international audience, some of whom sat with their eyes closed throughout.

There remains, however, a dissonance between who Schoenberg really was and what’s required of him for the sake of public engagement. The Centre preserves his legacy with a reassuring motto: ‘Culture – open for everybody!’ They are, no doubt, doing the good, hard work of getting people to listen to difficult music, but even a sincere slogan like this still narrows our vision of culture. Schoenberg openly rejected the idea that music can give a listener measurable results as a reward for their listening, cashed out in reliably ‘elevating’ experiences. There’s no guarantee that culture is always good for us, and it’s never going to improve us as people, no matter how open the venue.

Schoenberg was already in exile in Los Angeles when Hitler and his squad rolled into Vienna. The way figures like Schoenberg were humiliated, robbed, and murdered is well documented, even if the Viennese (and the Austrian state) would really like it if we all joined in with their version of events – not collective amnesia as much as a strategic misremembrance that adds one more layer of dissonance to Schoenberg’s legacy. The cultural-heritage industrial complex, represented by the Musikverein, were showing off for the birthday do, but the Arnold Schoenberg Centre admirably refuse to make him just another clockwork figure in this cosy art-nouveau toytown.

Comments