There is a basic political idea behind the Planning Bill announced in the Queen’s Speech. When you build a house, someone buys it – and when they do, they tend to start voting Conservative. The Bill’s aim is to get more houses built, 300,000 a year by the mid 2020s, helping to create millions more homeowners over the next decade and bringing long-term dividends to the Conservative party.

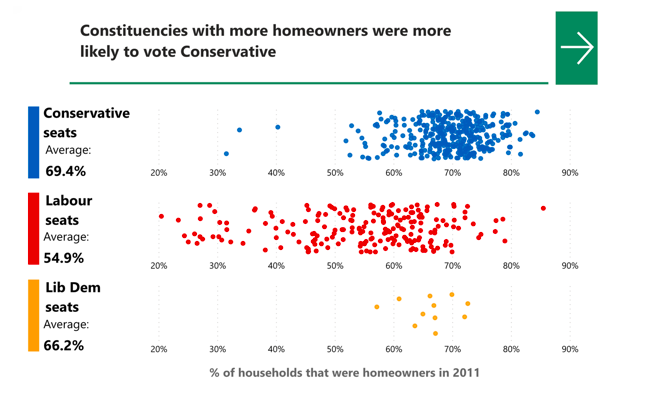

The data supports this idea: House of Commons Library research shows that at the 2019 general election, 57 per cent of voters who owned their home outright voted Conservative, as did 43 per cent of people with mortgages. Renters, both private and social, went in the opposite direction.

We hear lots about left-behind Red Wall voters; a bit less about the Red Wall family with a £40,000 household income, four-bedroom house in a decent village, two kids and two cars – who would see moving to London as a major lifestyle downgrade. For a long time, they have looked like Tories but voted Labour for tribal reasons. Brexit and Boris have changed that.

Building more homes isn’t just a political calculation – it should be a point of principle

But building more homes isn’t just a political calculation – it should be a point of principle. Home ownership among young adults has plunged in the last two decades. In the mid 1990s, more than two thirds of those aged 25–34 with ordinary incomes owned their own home. Twenty years later, that figure was just 27 per cent. The vast majority of my peers are stuck forking out huge chunks of their salaries on rent, while they struggle to save up for a deposit.

That has serious knock-on effects in millions of lives. YouGov data shows that huge numbers of young people are delaying job moves, putting on hold getting married and waiting to have children – all because of the housing shortage. This is bad news for anyone who values family life.

The good news is that this is what the Planning Bill will attempt to fix as it removes obstacles that get in the way of housebuilding. The biggest one is slightly unfairly dismissed as ‘Nimby’. These are the people who argue – often perfectly reasonably – against boxy new developments because they devalue existing homes and blight local places.

Building on the reforms of the last ten years, new legislation – adopting major Policy Exchange proposals published last year – will give Nimbys slightly less of an opportunity to do this, because there will be new fast-track routes to planning permission. Councils will need to ‘zone’ land as for ‘growth’, ‘protection’ or ‘renewal’. As Housing Today puts it, ‘Land zoned for growth will benefit from automatic outline planning permission, with councils unable to turn down applications that accord with local rules.’ Campaigners won’t like the sound of this because it means new developments getting through quicker than is possible now.

What should ease Nimby concerns is the Government’s focus on ‘building beautiful’. As Policy Exchange’s research on this subject has been highlighting since 2018, you are less likely to object to a new development that you can see from your conservatory if it looks more like Nansledan and less like the brutalist estates of the 20th century.

Our finding applies across all socioeconomic groups: 85 per cent of respondents across all socioeconomic groups said new homes should either fit in with their more traditional surroundings or be identical to homes already there.

Building in popular designs and styles is something that architects scorn but simply shows deference to what people like to live in and near. In urban places it might mean tree-lined terraced streets. In rural villages, it might mean using stone and slate that is in keeping with the local architectural vernacular.

The most important thing is to ask local people – and not outsider groups of activists – what they want. For instance, Ben Southwood and Samuel Hughes have argued in a recent Policy Exchange paper that streets of detached properties should be allowed to vote to form new terraces, and reap the financial rewards of increasing their own square footage. If that’s what people want, let them do it. Most people want the same thing: new housing, if it must be built, that preserves local value – and doesn’t lead to traffic jams and longer waits for GP appointments. The Government has a wider responsibility here to provide the necessary infrastructure.

This is essentially what ministers will need to argue, openly, over the coming months: there will be more houses. But new developments will be built in line with people’s concerns. The reforms will give design standards more weight than ever. And rather than being set by planning bureaucrats, these will be rules set by local communities, similar to existing neighbourhood plans.

This will amount to big changes for the housing industry too, who are already facing new Net Zero rules and safety measures. But ultimately more houses equal good business for them (and they have done very well out of Help to Buy). If they have to spend a bit more on materials to get more houses built, so be it.

Planning reform should also be about more than housing and this is likely to feature in the Bill later this year. In Italy, the new 1km San Giorgio Bridge in Genoa – built to replace the collapsed Morandi bridge – was delivered in just 13 months. It has become a source of huge national pride for Italians. Is the UK capable of this kind of achievement – of building the hospitals, schools, roads, prisons and other infrastructure that the public wants and the economy needs? We’ll find out when the Bill announced in the Queen’s Speech today reaches Parliament.

Comments