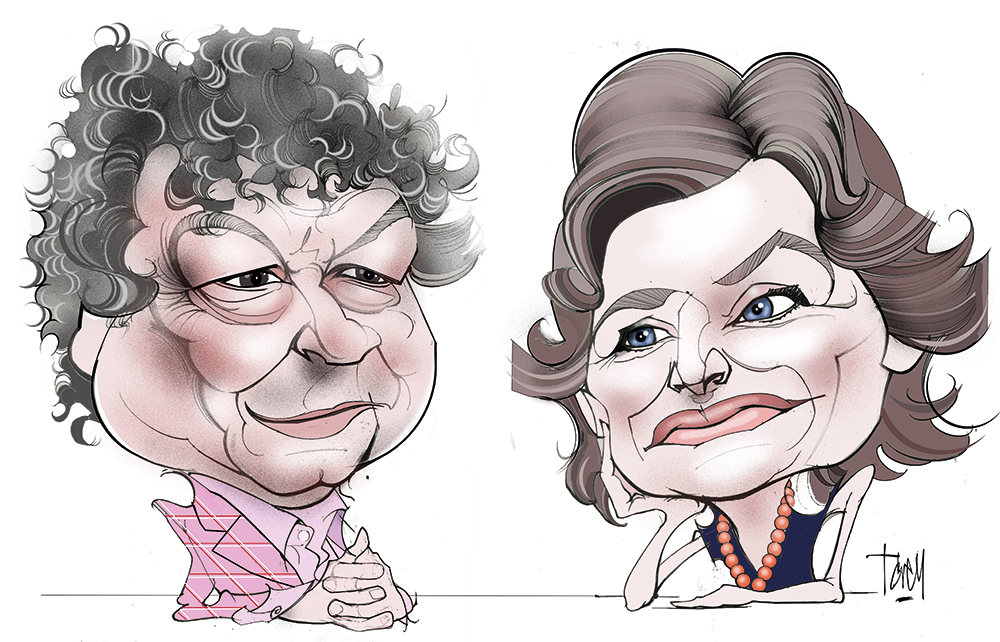

Mariana Mazzucato is a professor in the economics of innovation and public value at University College London. She speaks to The Spectator’s Wiki Man, Rory Sutherland, about the book she has co-authored with Rosie Collington, The Big Con: How the Consulting Industry Weakens our Businesses, Infantilises our Governments and Warps our Economies.

RORY SUTHERLAND: I’d like to start by congratulating you. The extraordinary growth in scale, wealth and influence of management consulting firms over the past 20 to 30 years is undoubtedly a phenomenon worthy of extensive investigation, particularly as it pertains to government contracts. We are effectively devolving decision-making to people who are doubly unelected in many cases and whose own interests may diverge fairly dramatically from the collective interest or the interest that government is supposed to be pursuing. So what fascinates me, working in an advertising agency, is that if I went to speak to Avis or UPS, I could plausibly comment on branding for those people but it would be an act of supreme hubris for me to waltz into those businesses on the basis of an Oxbridge degree in classics and claim to know more about car rental or transportation or distribution. Yet for some reason, if you put one of the big four or big three names on your business card, you are granted that licence to an extraordinary degree.

MARIANA MAZZUCATO: There’s this rubber-stamping that both companies and governments have gotten used to. They think: as long as you have a McKinsey or a Deloitte rubber stamp on a plan, ‘Oh then it’ll fly’. That’s a complete cop-out. An abandonment by government and business.

RS: In consumer decisions we’re trying to minimise the risk of regret, so my view is that we pay a premium for brands, not because we think they’re better but because we’re more certain that they are pretty good. I always argue that McDonald’s is the most successful restaurant in the world, not because it’s brilliant but because it’s incredibly brilliant at not being bad! Therefore you will always be drawn to a few consulting megabrands because they have a magical property which is if they mess up, everybody blames them but not you.

MM: Yes, but government gets blamed all the time, right. Look at the massive failure of the climate strategy that McKinsey brought to Australia. The government had already paid to invest in a public entity that had climate expertise, and yet they were so unconfident of using it to deliver climate strategy that they paid $6 million to McKinsey.

RS: There may be a case where there is a shamanistic value in expensive consulting as a commitment device. It’s a bit like an engagement ring; upfront expense is commitment to long-term intention, and that can be valuable. Shamanism can be valuable, even shamanism in pursuit of a non-perfect decision can be valuable if it at least creates some sort of unity and enables you to act.

‘When government starts to outsource, due to fear of risk, it actually becomes like a baby’

MM: The trouble is, you learn from your mistakes, you learn by doing, trial and error. So when government starts to outsource, due to fear of risk, it actually becomes like a baby. This is good for the consultants because then you have these infantilised governments that become addicted to you. You say let’s not blame the consultants. But governments need to wake up and to grow up. Health pandemics, climate change, the digital divide – all these problems require capable government, capable business and symbiotic and mutualistic collaborations, not weak government and parasitic collaborations. The parasitic relationship between public and private is the problem.

*****

MM: Actually, in pharmaceutical innovation and digital innovation and green innovation, the governments of some countries have always led. Darpa [Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency] did the internet, the CIA did touchscreen technology, the Navy did GPS and so on, but because we don’t admit that government can create value, we don’t end up doing the case-study research like Harvard Business School has for the private sector. We need to learn: what does it mean to develop a purpose-, problem-oriented government organisation? How does it work with other bits of the public sector in a dynamic way? How does it work with the private sector in a symbiotic and not parasitic way? So our book ultimately is one full of hope that we can do so much better. The role of consulting in the future should basically be to advise on the sidelines instead of being in the centre.

RS: There is a very unfortunate thing that I can see happening, which is what I sometimes call Soviet-style capitalism, which is that IT is in many ways bringing in central command and control through a back door. There’s a huge denial of tacit knowledge, a huge denial of learning by doing, and I call this the doorman fallacy. The fallacy is when you walk into a five-star hotel and you define the function of the doorman as opening and closing the door, you determine that can be replaced by an automatic door-opening mechanism. You fire the doorman and install, with your tech consulting partner, an automatic sliding door and then you walk away. Now what happens is that five months later you realise that the doorman performed a whole variety of tacit roles like recognition, status, security, sharing information with other doormen on potential dodgy guests, and what you discover is that after you’ve banked those false economy savings, six months later your rack rate is 50 per cent down and vagrants sleep in your entrance. But as far as you the consultant are concerned, your project was a complete success because you banked savings within the very narrow way in which they were defined.

MM: In the book we look at how the government is weakened when there is no more real thinking around issues like public value, public purpose. Public value, by the way, is a measure within the BBC. It holds the BBC accountable when it’s doing things which in theory might be more business-oriented, like talk shows and soap operas, versus the classic market failure of high-quality news and documentaries. I have yet to find a Department of Health, a Department of Defence, a Department of Energy, a Department of Innovation in the UK that has an equally interesting dynamic vs static metric that says we need public purpose in the public interest but we also have measures to hold us accountable. So today, when we are hearing from Keir Starmer that we need to reform the NHS, the risk there is it’s using the same language; there is no re-imagining of the language we actually require to strengthen the NHS, make it more dynamic and capable and help it to work alongside other actors. That’s what a progressive agenda should look like and yet we are going back to the idea of just focusing on the waiting lists.

‘It wasn’t a surprise that Deloitte failed. Was Test and Trace in its expertise portfolio? Of course not’

RS: One of the things we have to talk about is just the question of language. For consultants and in IT for some reason, if you talk about something in technological terms or in economic terms, it accords you very high status, and if you talk about something in practical terms it doesn’t. One of the things that I noticed at the very beginning of the pandemic was government was making huge pleas to people like Google and Facebook, and the one thing I did say was the people you need to be talking to here are actually Royal Mail, because they deliver 80 million things every day.

MM: Look at the vaccine rollout, in which the NHS and the community GP practices did so amazingly, unlike what Deloitte ended up doing with Test and Trace. It wasn’t a surprise that Deloitte failed. Was Test and Trace in the expertise portfolio of Deloitte? Of course not. So, it’s interesting that even the UK government, which has been susceptible to all this outsourcing, privatisation and consultification, actually continues to have some really good examples – the vaccine rollout, GDS and so forth – that we should be learning from. It’s not like the civil servants actually think that McKinsey or Deloitte or KPMG are actually producing all this value. They all know the system is broken.

*****

MM: It’s not that all consultants are bad, the problem is how this industry is set up.

The business model underlying it is open to conflicts of interest – so in South Africa consultants are advising both ESKOM, the state-owned enterprise, and the Treasury, both sides of the street. The lack of transparency and the decimation of these internal capabilities that we require in the public and the private sectors, these are huge problems that the world knows about but

what do we do about it? We need a functional consulting industry and I think what we’d like to do after the book is published is to run some workshops with the industry, the private sector, the government sector, to find a way forward that makes sense.

RS: An entrepreneur has one huge advantage over a larger institutional business or government, which is that he or she does not have to justify every single decision to somebody else and therefore is free to make bets which on the basis of conventional rationality seem insane. I always give the example of Red Bull. The most successful attempt to compete with Coca-Cola in 50 years comes with a drink that costs more, comes in a smaller can and doesn’t taste as nice! Dyson – there is no evidence before Dyson existed that there was a market for a £700 vacuum cleaner. Every single bit of data you looked at basically would have told you to forget it and anyway, anybody who has got £700 to spend on a vacuum cleaner probably doesn’t hoover their own home. Now, the freedom to take those divergent bets comes into conflict with the assumption in all institutions – not only government but also business – that the quantity of information and the degree of rationality is a good proxy for the quality of a decision, and this is a philosophical question. Gerd Gigerenzer would be one of the people who interestingly dissents here by saying that, in some cases, less information can lead to better decisions.

In some cases, the way I always put it is that there are more good ideas you can post-rationalise than there are good ideas you can pre-rationalise. Entrepreneurs are free to explore the ideas that you can only post-rationalise, you can’t pre-rationalise. If you are in an institutional setting and your job’s at stake, and bear in mind the asymmetry of incentives is enormous because if you do something rational, if you succeed you get a pat on the back, if you fail it’s not your fault. If you do something that you might call hypothetical, you do something slightly braver, if you succeed you probably get the credit stolen by someone else, and if you fail, you lose your job.

MM: Yes, but Rory, instead of saying, ‘Oh, the public sector is large and bureaucratic so it can’t be entrepreneurial’, we need to reinvent bureaucracies to be creative, flexible and agile as they have been shown to be in some moments of history that we should be learning from.

Any venture capitalist will tell you that for every success you are going to have ten failures, but that’s always been just as true for government when it is doing really difficult risky things. So the question is, do we want government just to sit back, correct market failures and not engage with risk, not engage with the big challenges of our time? That kind of mentality is what gets us weak government.

So it’s a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy, thinking entrepreneurship is just in the private sector and we have these big boring bureaucracies that at best should build motorways, infrastructure, give a bit of money to SMEs, build schools and then get out of the way – that’s the kind of myth that we need to debunk, because what we need is creativity and entrepreneurship in both sectors, public and private.

RS: But can we create a media environment where government is allowed to make any mistakes, even if it learns from them?

MM: That’s a longer conversation, probably with drinks.

Comments