A parliament is an odd place. It’s the arena where clashing worldviews come to cross swords and there’s low and ugly skullduggery. In most other workplaces, political differences are a topic to be avoided, but the job of a parliamentarian is to spend day after day with colleagues whose values they abhor and whose ideas they consider harmful.

For all the florid patter back in 1999, about how the Scottish parliament’s electoral system, working practices and even semi-circular chamber would fashion a more collegial politics, Holyrood has proved every bit as factional and partisan as the House of Commons. Yet, like the Commons, exposure and proximity to political foes engenders a grudging respect, even as it sharpens ideological differences. Hating people from afar only generates more hatred, hating them up close can inspire respect and even affection. Familiarity breeds contempt, but contempt sometimes breeds familiarity.

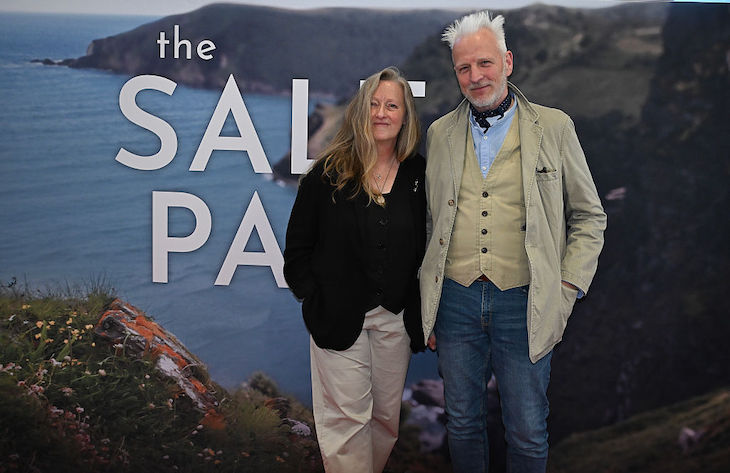

The death of Christina McKelvie therefore loomed not only over the SNP benches but across the Holyrood chamber today. The Minister for Drugs and Alcohol Policy, a member of the Scottish parliament since 2007, died from breast cancer this morning. She is survived by her partner Keith Brown, deputy leader of the SNP, and their sons Jack and Lewis. She was 57. It is no age.

A few minutes before weekly question time, MSPs gathered for a moment of silence. Alison Johnstone wore the grief across her face and in her voice. The Presiding Officer eulogised ‘a determined and passionate campaigner for social justice and an engaging parliamentarian’, and recalled McKelvie’s various kindnesses to her.

John Swinney cut a solemn figure. It was, the first minister told the chamber, ‘an unbearably sad day’. The Hamilton, Larkhall and Stonehouse MSP was a woman of ‘the highest motivation and the finest nature’ and his party was ‘aching at the news’ of her passing.

Scottish Conservative leader Russell Findlay paid tribute to ‘a respected colleague and a dedicated public servant’. No one was in the mood for a partisan punch-up, but this was still First Minister’s Questions and questions had to be asked. Findlay raised an Audit Scotland report on the dire state of GP services, urging Swinney to commit to implementing five key recommendations, but was able to extract only an undertaking that ministers would ‘consider’ the proposed changes. Findlay pushed a little more but not much. The appetite just wasn’t there.

Anas Sarwar remembered McKelvie as a ‘dedicated local MSP who was ‘fierce politically at times but also good fun’. It was about time someone said it. McKelvie was not some prim-and-proper spouter of press release pap. She was a warrior, not least of the keyboard variety, and some of the stuff she used to post on Twitter back during the independence referendum was weapons-grade cybernattery. She was infuriating.

But she was also bold and bolshy and funny and she believed in stuff. The stuff she believed in was almost invariably wrong, but she wasn’t a soulless careerist, prepared to sing whatever song would get her promoted. Whatever sincerity is worth in politics, she had it in bucketfuls. Still, I thought Nicola Sturgeon had taken leave of her senses when she elevated her to the ministry in 2018. She proved, however, a hard-working and capable minister.

Her causes were those of the progressive left: equalities, human rights, and international cooperation. She was an advocate for trans rights, pro-Europeanism, and Palestine. Unsurprisingly, she found a friend and ally in Scottish Green leader Patrick Harvie. His nasally register broke into a softer, sadder tone as he spoke of how the parliament had ‘lost one of our very best today’, and how McKelvie had remained committed to her principles her whole career through.

She was infuriating.

But she was also bold and bolshy and funny and she believed in stuff

‘Her life and extraordinary spirit,’ he said, ‘deserve to be celebrated,’ and his only question to the first minister was how her fellow MSPs could be more like McKelvie. In reply, Swinney recalled her ‘generosity of spirit’ and observed that ‘if anyone was facing a moment of difficulty, the first person at your side would be Christina McKelvie’.

I know what you’re thinking: that’s all well and good, and it’s sad that she died, but they were sent to parliament to represent their constituents. They should have offered a few warm words then got back to business. I disagree. Bereavement is a spectre that stalks us all, and whilst we know that, we are seldom prepared for the day it accosts us. Perhaps that is because we avoid thinking and especially talking about death and loss and what it’s like to be left behind. To be apart from our loved ones for a prolonged period is unpleasant but the final estrangement is unbearable.

Anglo culture has long viewed grief as a private affair, with emotions to be cloistered in sombre sitting rooms, filed away in family albums, and boxed up tight in attic rooms physical and mental. Reserved and dignified at all times, old bean. Maybe it’s the Catholic in me, maybe it’s the Irish heritage, but this cast of mind is alien to me. A pretence of composure is not dignified. It is a dishonour to the dead and a deceit of the living. There is a place in public life for emotion, for sorrow, for shedding tears for those we loved and cared about. There is, even in our very secular politics, a time for setting aside routine duties to observe deeper obligations, for pausing the current thing to reflect on the eternal thing.

Christina McKelvie meant something to those who knew and loved her. The parliament she served in is not so odd that it shouldn’t stop to acknowledge that.

Comments