Waiting to appear before a Commons select committee, my father turned to me. ‘This was not on my bucket list,’ he said.

My father should be enjoying his retirement. Instead, he and my mother are still working full time in their seventies because they cannot sell their home due to the blight of HS2. And here they were now, about to present themselves to Parliament to petition the High Speed Rail Bill.

Theirs is one of more than 1,900 petitions brought by people whose lives have been so adversely affected by the planned rail link that they will need to be heard in person by MPs before the Bill can be passed.

Because of their age, I decided I would be the one reading a statement to the cross-party committee examining the effects of the Bill. The way I felt, standing outside committee room five of the House of Commons, I would need a bucket list myself soon.

Our appearance was the culmination of months of wading through mountains of paperwork, poring over endless maps and gathering evidence that went into such minutiae about our lives that it has all too often felt like we are the ones on trial, not the government’s controversial rail project. I don’t know how anyone fights these battles. No. Let me put it another way: I know exactly how governments and big corporations wear people down so that objections to infrastructure projects by the poor helpless sods caught in the middle are seldom any problem for the guys at the top.

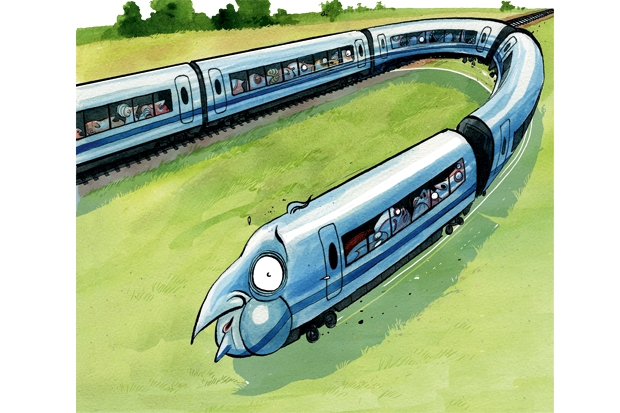

For the past five years my parents and I have been living in the shadow of a rail link that many, including some senior members of the government, believe will never be built. Its cost is spiralling, and now estimated to be the better part of £100 billion. It’s an outdated project, the answer to last century’s transport question. High-speed rail was something Britain needed a long time ago — possibly as far back as the 1960s, when the first bullet train was hurtling through Japan. But the growth in technology like free conference-calling has made nonsensical the claim that economic growth will be boosted now by business people shaving 20 minutes off the journey between London and Birmingham. If the digital revolution continues apace, most of us won’t make this journey soon at all. At around £100 a ticket, the line will be the preserve of rich tourists.

Not since the Millennium Dome has so much taxpayers’ cash been lavished on something of such dubious application. But as one very senior cabinet minister put it to me: ‘They’re being very arrogant about it. Big trains, you see. It’s all a bit macho.’ By ‘they’, I take it he means Cameron and Osborne, particularly the latter, for whom the HS2 link seems to be something of a passion.

Well, he doesn’t have to worry about its impact. In plans showing the second leg of the line going north from Birmingham, it suddenly goes in a £600 million loop around Osborne’s Tatton constituency.

Gallingly, though, it was not Osborne but my parents, with their modest three-bedroomed semi, who were called ‘toffs’ at the height of the HS2 debate. Going head to head with me on Sky News a few years ago, the late Bob Crow denounced my family for not wanting the line near their ‘country estate’. They were, he said, sacrificing transport workers’ job prospects.

Oh, the irony. My father gets up at 4 a.m. to work in the car industry at the age of 77. He can’t slow down because the neat little house he worked all his life to pay for has devalued drastically because of the actions of a remote elite. The fact that neither the left nor the right get this has been uniquely deranging.

When Philip Hammond visited the areas affected as transport secretary he denounced concerned residents as nimbys and luddites. But the reality is, those facing ruin are neither flat-earther nimbys nor toffs in the Chilterns but ordinary people whose only asset is their home. The burden of HS2 falls disproportionately on the hard-up and the elderly because they are the ones who cannot just walk away from their blighted property and start again.

It doesn’t help that whenever we tell anyone that our lives are pretty much taken up with fighting HS2, they always shrug and say, ‘Oh that! But they won’t build it.’

Here’s the thing; it doesn’t make any difference whether they build it. Homes are already up for sale and cannot be sold. It makes me mad as hell to see my mother being brave about the arthritis in her hands as she continues with her hairdressing business.

And it’s not as if staying put will only mean financial hardship. If they are unable to move, they will spend their eighties living next to a massive construction site, with 246 workers stationed in the fields around them. The road on which they live will be closed one way, making journeys to the nearest town to get provisions intolerable, while hundreds of HGVs carrying materials will choke out dust and diesel.

And if they are still alive when it’s finished, they will be nearly 90 years of age and living 335 metres from a massive rail link and right next to a flyover — because the plan is to raise the end of their road into the air and send 225mph trains underneath it every four minutes.

All that upheaval, and the attitude of those in power so far has been to tell them to rejoice and be proud of this wonderful new infrastructure project. Let them eat construction dust, effectively.

What affects me more than anything is the fact that my father put his trust in the process. A Tory voter all his life, he believed a Conservative-led government would do the right thing. And so after the project was confirmed by the coalition, he spent a good deal of time waiting for an envelope to plop through the door explaining what they would do to help him. It took years of receiving only high-handed missives from the Department of Transport for him to realise no help was coming.

At first we were discouraged from even thinking about the only scheme available — called the Exceptional Hardship Scheme — because so few householders had been helped by it. But eventually we realised that other putative schemes were not materialising. So earlier this year we started spending my parents’ dwindling income on lawyers to help us navigate the unbelievably complex process of applying to the EHS and petitioning the HS2 Bill.

Waiting outside committee room five, it all seemed such a blur. My parents went in to take their seats and then it was just me sitting on a bench outside with a clerk swearing me in. As I stared at the laminated sheet on which the oath was written, everything was swimming in my head. On the Wandsworth Road that morning we had got stuck in traffic and so, fearing we would miss our slot and all would be lost, I got out of the minicab and ordered my poor parents to start running. Thankfully, we managed to flag a black cab and sail through the bus lanes. But it was all too much. I had wanted to protect them in their old age, and I felt like I was failing.

I burst into tears. The clerk looked at me askance, before disappearing. He returned with loo roll and a glass of water.

Somehow I said the oath, wiped my eyes and got myself in front of the committee. Our legal team, Simon Ricketts and Evan Milton of King and Wood Mallesons, who have worked incredibly hard for us and way beyond the call of duty in holding me together, visibly exhaled with relief when I took my place beside them. Simon looked a little nervous as I began.

But in the event, I didn’t shout and scream about the injustice of it all. I managed to stick to the facts, calmly referring to maps and reference points in baffling HS2 Ltd documents. And when I had finished, I thought, ‘I don’t care what happens now.’

In fact, Sir Peter Bottomley said he thought our case an obvious one for compensation. Robert Syms, the chairman of the committee, said they would follow our progress and if the compensation scheme ‘is not doing what it says on the tin then we will want to have some words’.

Back in the corridor, the representatives of HS2 Ltd scurried up. A conversation between our legal team and their legal team ensued. I didn’t dare hope. I still don’t. Our case is now being examined by a panel.

In the past few days, we have had to submit bank statements, pension books and savings accounts to prove that my parents do not have vast amounts of money stashed away. We have also had to produce yet more utility bills (we’ve submitted about a dozen) as proof of address. It is as if the government seriously thinks it is possible my parents might be making up the whole story about living next to the HS2 route.

If only.

Comments