On a recent Sunday evening, the Shaftesbury Theatre in Soho was packed to the gills with a crowd celebrating a dramatic tribute to a landlord: the best kind of landlord, the landlord of a pub. And not just any old pub, but the pub he ruled with an iron fist for 63 years until his retirement in 2006. Ladies and gentlemen, I give you Norman Balon, sole proprietor of the legendary Coach and Horses. ‘London’s rudest landlord’, as he was known; it said so on the matchboxes.

On for one night only, Norman Balon – It’s All True was a play written by the person who took over the lease, Alastair Choat. It followed in the footsteps of Keith Waterhouse’s Jeffrey Bernard Is Unwell, which in 1989 established a precedent for West End plays set in this pub.

The pub itself has certainly been the stage for plenty of real-life drama. I first stepped warily into the Coach in 1984; I was 21. I had graduated with a useless degree. It was time to pick up some life experience. Some people travel the world. Some embark on careers. Some run away to join the circus. And some… go to the pub. But not any old pub.

A year before, my best friend (he still is) had recommended I read The Spectator. I curled my leftie lip. ‘Give me one good reason,’ I said. He showed me Jeffrey Bernard’s column, ‘Low Life’. For those of you too young to have read it in its first incarnation, this was a weekly (when Bernard was sober enough to write it) chronicle of the exploits of a small group of Soho wasters, passing the time from the moment the bolts slid back at 11 a.m. to the moment they were ejected, 12 hours (plus drinking-up time) later.

For a few years, the Coach and Horses became my living room, my bank (you could cash cheques there) and even my bedroom

There were two dead hours in the afternoon when the pub closed, during which time the customers wandered Soho like lost souls, decamping either to the Colony Club or one of the even less salubrious dives which were the only way to be served alcohol in the afternoon. Around six o’clock those still able to walk went back to the Coach, so they could be insulted by Jeffrey Bernard; or, indeed, Balon. I was hooked. A gallery of wastrels, among whom I felt immediately at home: ne’er-do-wells living between irregular paycheques, chancey loans or, rarely, but not for want of trying, gambling winnings.

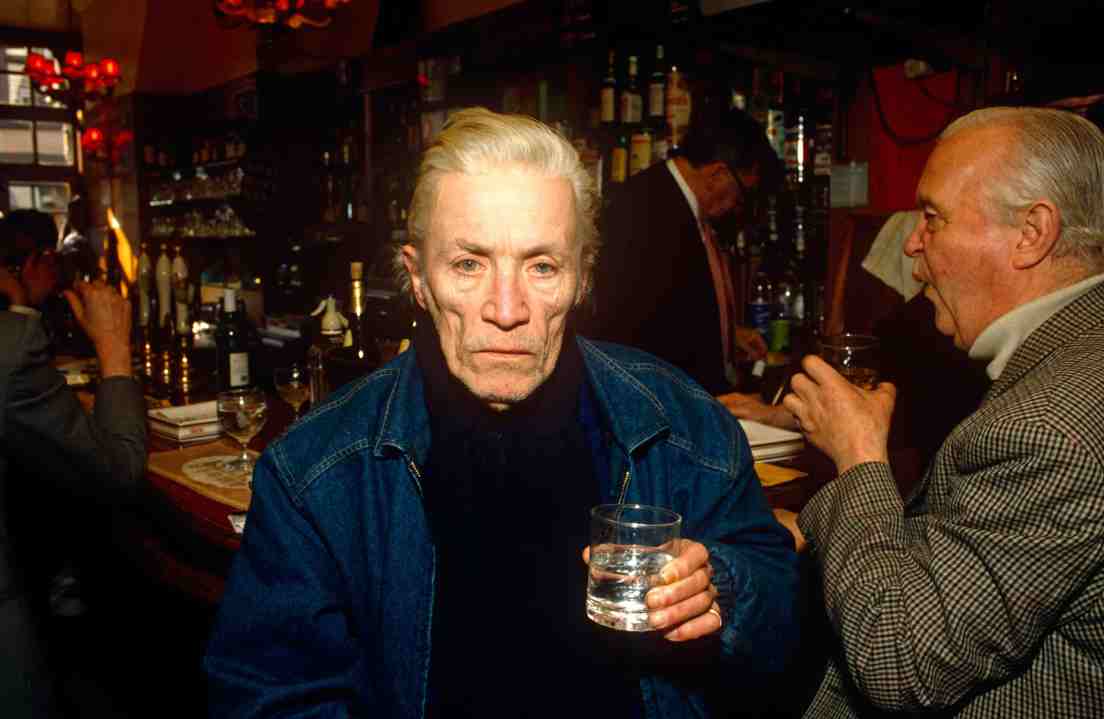

Soho these days is a pale imitation of its former self: people have been saying that for decades. They were certainly saying it in the 1980s when I started going there. Bathetically, I had at first gone to the wrong Coach and Horses, a distinctly ordinary pub on Charing Cross Road. I looked around for Jeffrey Bernard, but no one seemed to fit the bill. (Bear in mind that I didn’t really know what he looked like. You couldn’t look people up on the internet.) So I wandered around until I found the real Coach: one look at the end of the bar, where Bernard was unmistakably holding court, told me I had gone to the right place.

But there was one person there who had, if anything, more charisma than even Bernard: and that was the landlord, Norman Balon, who to my eyes looked like a giant of a man, a figure from ancient myth, brooding and hulking over his regulars with an eye that contained either scorn or mockery. Here was someone nobody in their right minds would mess with. Of course, by about seven o’clock almost nobody was in their right mind any more, and so on a regular basis you could hear him bellow his legendary catchphrase: ‘Fuck off, you’re barred.’ That Balon was quite obviously Jewish only added to his aura of Old Testament deity. Here was authority incarnate: the ultimate father figure. I had a perfectly good father of my own, but he didn’t run a pub, and he lived in East Finchley, which is as far, spiritually, from Soho as you can get.

And I learned. There was no strict curriculum. That was the point. You learned to hold your drink, perhaps; but more crucially, you learned what the rest of the world looked like. For Norman presided over a kind of ideal classless society; classless in both senses, in that quite a few of the regulars had no class, but also that the best of them had disengaged themselves from the 9-5, and any notion of the class system. And this was another crucial lesson: you learned how to distinguish between people who acted like bullies and were, or people who acted like bullies and were very much not. Norman was big and scary but everyone knew he was on the side of justice. Those he had barred crept back in sheepishly a few days, weeks or months later and were, implicitly, forgiven, at least until their next transgression. It was, in its way, a comforting cycle.

So for a few years, the Coach became my living room, my bank (you could cash cheques there) and even my bedroom. I went out for a while with Debbie, the incredibly beautiful Scottish barmaid. This often involved staying the night in her room above the pub. This was my idea of heaven. The first time I came down in the morning, Norman was cleaning up, and said: ‘What the fuck are you doing here?’ But this only made me smirk harder.

A few weeks later Debbie told me it was over, and the way she put it made me think: ‘God, has Norman barred me from you?’ It turned out Jeffrey Bernard had wooed and won her. As I had two other girlfriends at the time I took it philosophically. A couple of weeks later, she worked out a fifty-something diabetic alcoholic might not be her best bet and she came back to me. One evening I was sitting at a table with friends and Norman came over. ‘Here he is,’ he said. ‘Worst lay in Soho.’

Later on I was at my first Private Eye lunch, held upstairs at the Coach, and Norman came to take orders for his abominable food. He did a double-take when he saw me and said, again: ‘What the fuck are you doing here?’

We bonded still further at Jeffrey’s funeral; and then at Deirdre Redgrave’s, with whom Bernard had had, after I’d introduced them, a fraught relationship. There was no rudeness that day; just the big heart he carefully concealed.

By that stage I had started a family and the Coach was in the past. I had asked myself the question ‘What the fuck am I doing here?’ and come to the conclusion that it was time to move on. And so many had already done so, without volition: the attrition rate among the regulars was as you would expect given the lifestyle.

But Norman, teetotal as always, is still with us, in his nineties, and I was overjoyed to shake his hand again on that Sunday evening; for he is one of the immortals.

Comments