We may look back to find Sir Keir Starmer partly defined by the phrase ‘coalition of the willing’. It is hard to fault the prime minister’s energy in rallying nations to implement a peace settlement in Ukraine, but there are issues to unpick. Who makes up the coalition? What is its role in Ukraine? What forces and capabilities will it need to fulfil that role, and where will it get them? The answers to these questions are both vague and subject to change, so let us see what we can establish.

Only two months ago, President Zelensky told the World Economic Forum that enforcing a peace settlement would require a force of ‘at least 200,000… a minimum. It’s a minimum, otherwise it’s nothing.’ That figure has been revised significantly downwards as reality bites: when he visited President Trump at the end of February, Starmer pitched a figure of around 30,000, while this week the talk has been of a ‘reassurance force’ of ‘more than 10,000’.

When Starmer convened the first summit at Lancaster House on 2 March, 16 nations participated: the UK hosted Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Romania, Spain, Sweden, Turkey and Ukraine. He promised that Britain would contribute ‘boots on the ground, and planes in the air’. A conference call last weekend included more than 30 countries, with Australia, New Zealand and Japan now involved; UK officials conceded that not all of these will provide military contributions on the ground.

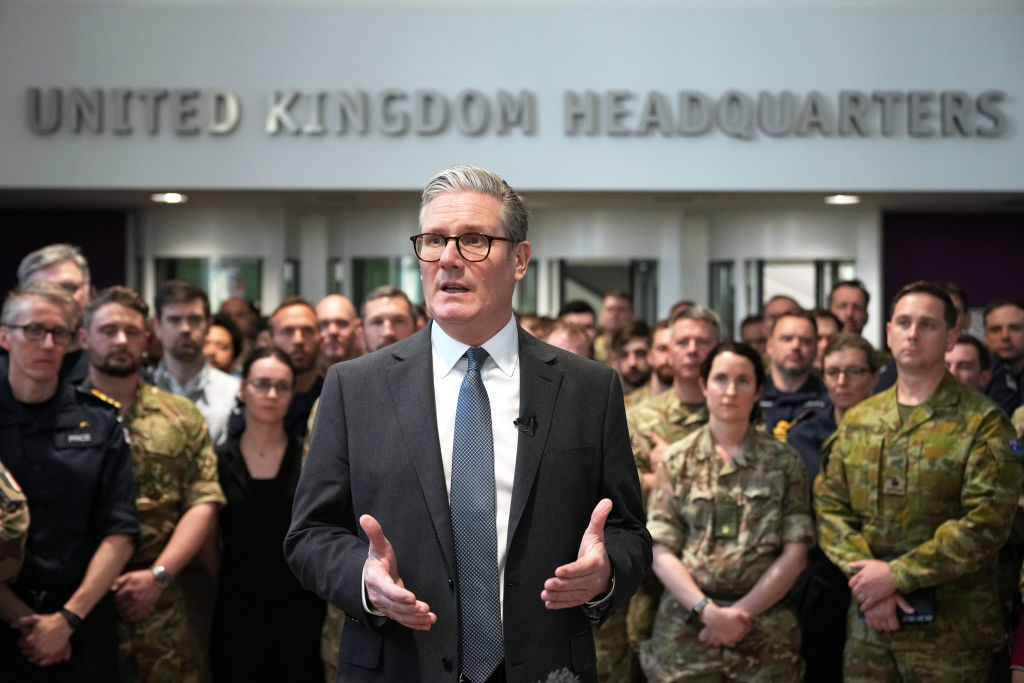

On Thursday, senior military personnel convened at the Ministry of Defence’s Permanent Joint Headquarters at Northwood to develop more detailed operational plans for a ‘reassurance force’. Although UK sources deny it, some in attendance felt that the prime minister’s focus was shifting away from deploying substantial ground forces towards the potential role of air and sea power in policing a peace settlement.

Realistically, what can the UK offer? As part of a total deployment of 30,000 or even 10,000, the British Army will be extremely hard-pressed to find even a brigade-sized force of around 5,000. There is an inexorable logic: six-month rotations means a total commitment of 15,000, which is a fifth of the army’s entire strength. The government has ruled out ‘pulling back from our commitments to other countries’. There is very little slack.

Downing Street has said for weeks that American support is vital, and that a UK deployment ‘must be in the context of a secure and lasting peace with US backing being needed’. Starmer has talked of a ‘backstop’, meaning, in the last resort, US air power, logistics and intelligence. This is simply not available and there is little sign of that changing.

It is very difficult to make the numbers work

Of the other coalition members, Downing Street has claimed that ‘a significant number of countries’ would contribute ground forces. France would almost certainly do so, and Turkey, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, Denmark and Sweden might follow suit. Italy has ruled it out as has Finland, while Poland, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania, which all border Russia, are more likely to prioritise securing their own frontiers. Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk last month said: ‘We do not plan to send Polish soldiers to the territory of Ukraine.’ Assembling a strength of 30,000 looks daunting.

The UK does not have much flexibility in the air or at sea either. There has been a suggestion that the RAF could deploy Typhoon fighter aircraft to keep the peace from above. It has 137 Typhoons in total, of which 26 of the oldest are due to retire this month. The others are committed to national air defence, British Forces Cyprus, Qatar and Nato’s Air Policing mission in Poland.

Whatever size this reassurance force is, it must deter Russia from breaching a settlement (if one were ever agreed). Russia has 600,000-700,000 soldiers committed in and around Ukraine, from a total military strength of 1.3 million active personnel and two million reserves. Some reassurance.

Military planners are meeting again next week, this time in Paris. But it is very difficult to make the numbers work. The UK armed forces are already more than stretched – although it is reported that Special Forces have been placed on stand-by – and only a handful of other countries currently seem reliable in terms of ground troops. The reassurance force would be tiny compared to Russia’s strength, and it cannot rely on US assets; nor do we know what it would be expected to do. This feels like diplomatic kabuki, ritualistic, stylised but with little connection to the real world.

Comments