‘Can you come Saturday morning to my studio, 19 bis rue Fontaine?’ Degas wrote to Edmond de Goncourt in 1879. ‘From 10.30 to half-past noon, I will have my négresse and her partner who will come expressly to be at your disposal.’

Not content with dangling from a rope by her teeth, she suspended a 300-kilo cannon barrel from her jaw

It’s not what it sounds like. The ‘négresse’ in question was Anna Albertine Olga Brown, stage name Miss La La, an aerialist at the Cirque Fernando who had been sitting – or more accurately hanging – in Degas’s studio for a painting for that year’s fourth Impressionist exhibition. As his friend was working on a circus novel, he thought he might be interested in meeting her. Degas was clearly proud of his catch: Miss La La was a celebrity. She and her partner Theophilia Szterker – stage name Miss Kaira – were ‘envied models for the painters of the neighbourhood’ according to L’Orchestre. She was far more famous than the artist. Since opening at the Cirque Fernando the previous December, the trapéziste had Paris at her feet: ‘To admit that you have not seen her is to lose your reputation as a Parisian,’ declared L’Orchestre.

Miss La La’s was not just any trapeze act, it was an ‘iron jaw’ act with a difference. Not content with dangling from a rope by her teeth, she suspended a 300-kilo cannon barrel from her jaw while hanging by her knees from the trapeze – and didn’t flinch when it fired.

In photographs she has a surprisingly small chin and a sturdy body: her biceps, measuring 15 inches in circumference, were the envy of the physiologist who examined her. Under 5ft tall but ‘as muscular as the Farnese Hercules’, reported L’Orchestre, she was an object of fascination not just because of her gender, but her race.

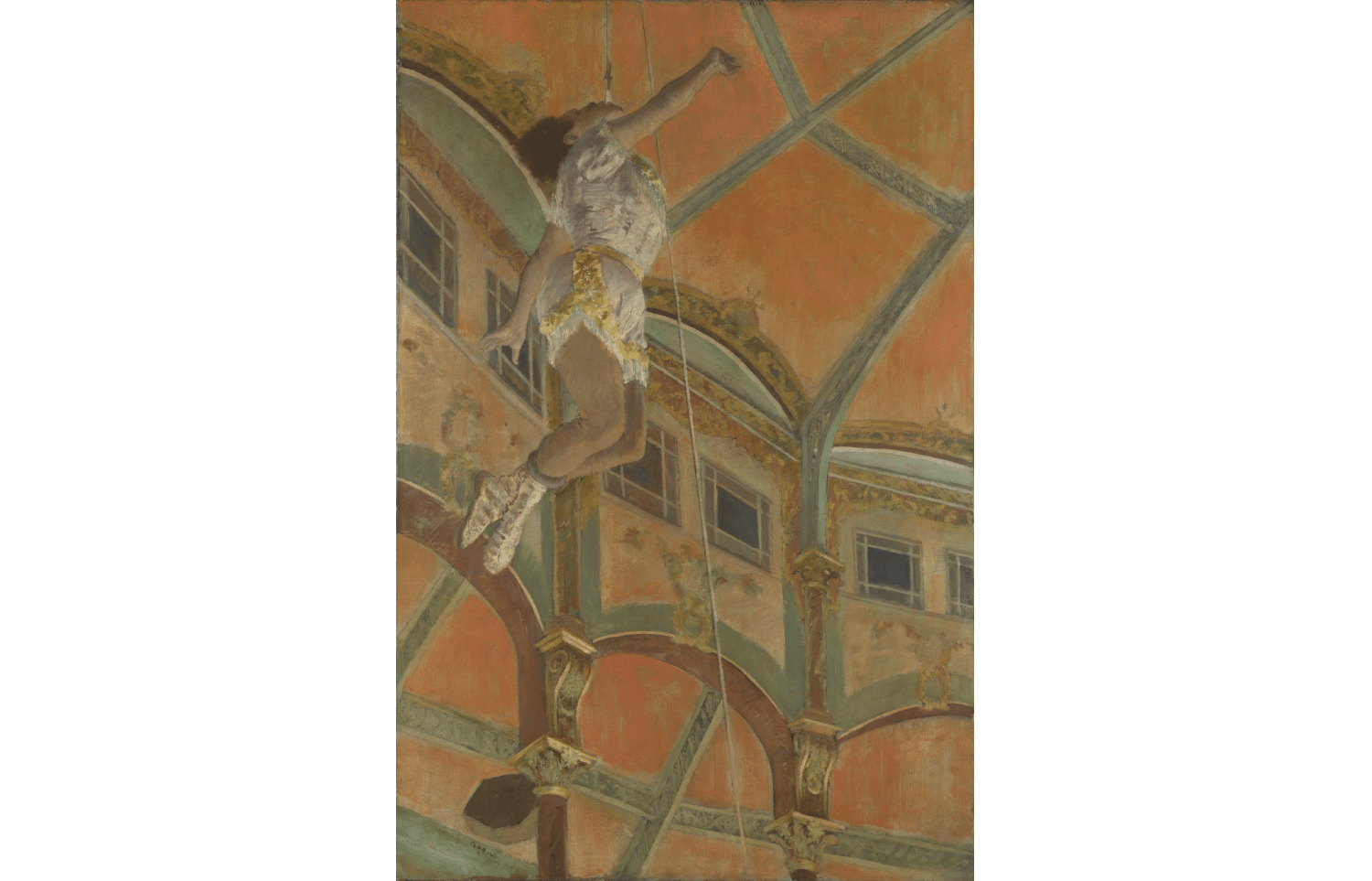

Born in West Pomerania to a German-Prussian mother and an African-American seaman who had found work in a local wood yard, she was not quite the ‘Venus of the Tropics’ advertised – in 1870s Paris, her Prussian origins were not a selling point. But they had set her on the path to stardom. Gymnastics were an important part of the Prussian school curriculum, and she excelled at them. She had been flying the trapeze since the age of ten, but it was the Cirque Fernando contract she signed aged 20 on the strength of her cannon act that shot her to fame. A few blocks away from Degas’s Montmartre studio, the circus was a favourite haunt of artists and Degas was a regular; in January 1879 he began sketching Miss La La during rehearsals. It wasn’t her cannon act that interested him so much as the poses she struck as she was hoisted to the roof with a rope clenched between her teeth. Alongside drawings in sketchbooks, the National Gallery’s revelatory little show contains larger studies made in the studio and an early attempt in oil that included the audience, omitted from the final painting we know as ‘Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando’ (1879).

In the 19th century, female circus acts were displays of the performers’ legs as much as of their prowess. But whereas Renoir’s contemporary painting of two young ‘Acrobats’ in the exhibition is mildly voyeuristic – a male spectator in the front row is training glinting binoculars on the teenage girls – Degas’s is not. As with his images of dancers exercising or women washing, his focus was on the physicality of the female body. His methods were traditional, but his vision was not. He liked to capture the body off-guard from awkward angles that lent a daring authenticity to his imagery, an approach this painting’s sotto in sù perspective took to new heights.

Degas didn’t silhouette Miss La La; he painted her in the glow of the circus’s gas chandeliers

The exhibition links Miss La La’s ethnicity with the artist’s family background in New Orleans: his mother was Creole and had mixed-race cousins. Degas spent the winter of 1872-3 in New Orleans where his brothers René and Achille had a cotton export business; while there he painted ‘Courtyard of a House, (New Orleans, Sketch)’ (1873) featuring his nephews and nieces with their nanny, the only image of a black person he brought back. ‘The black world, I have not the time to explore it,’ he regretted in a letter to James Tissot; ‘there are some real treasures regarding drawing and colour in these forests of ebony.’ Dark skin heightened the contre-jour effects he relished. ‘I shall be very surprised to live among white people only in Paris,’ he went on. ‘I love silhouettes so much and these silhouettes walk.’

Degas didn’t silhouette Miss La La; he painted her in the glow of the circus’s gas chandeliers. Her face is turned away, suggests Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby in the catalogue, because he ‘could not look black people in the eye’.

But Degas rarely focuses on the faces of his female figures, whether dancing or bathing: anonymity lends them universality. He had no wish to paint a celebrity portrait of Miss La La. He wanted to frame a woman’s body twirling in space in a painting that was itself a high-wire act.

Comments