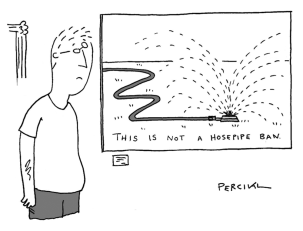

What has happened to Britain’s rivers isn’t a mistake. The fact that serious pollution is up 60 per cent on the year, or that only one in seven rivers can be called ecologically healthy, is the result of corporate tactics. It is effluent from the murky world of private equity.

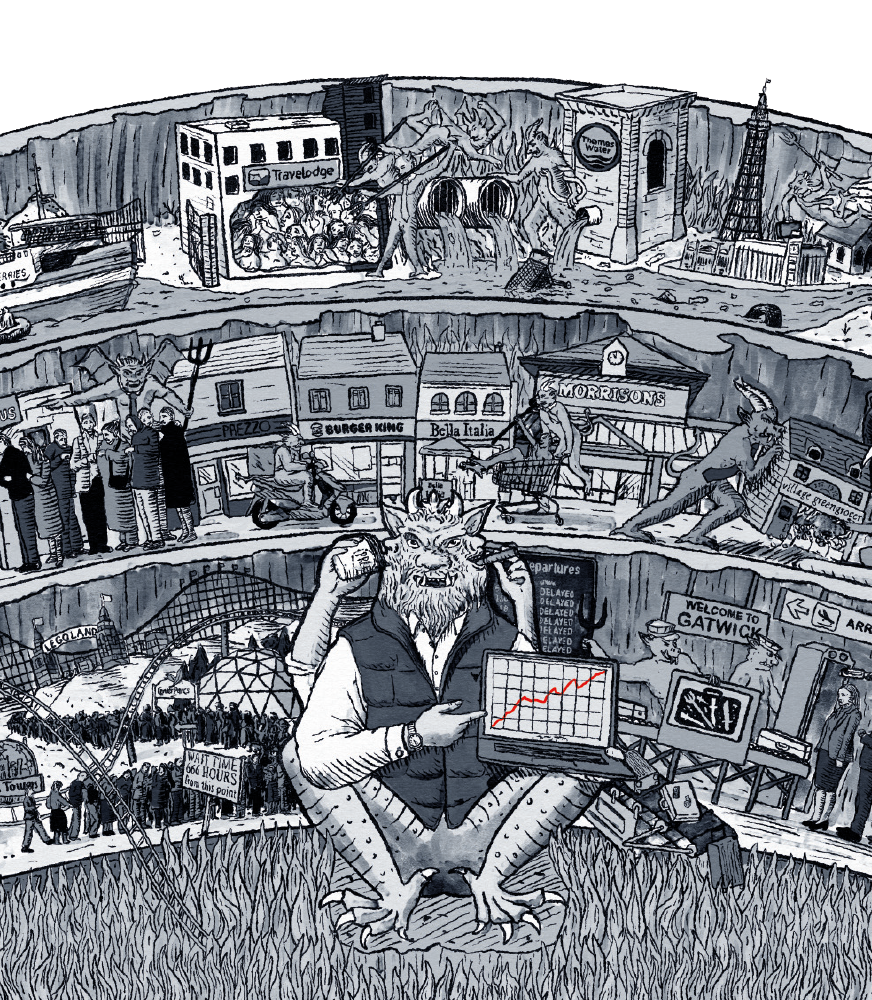

Some 2.5 million people in the UK now work for a business that is ultimately owned by private equity. Since the 2008 financial crisis, Britain has become a prime target for takeovers, driven by low company valuations, favourable exchange rates and a pliable regulatory environment. Everything from Bella Italia to the Blackpool Tower, Travelodge to Legoland, the AA to Zizzi, has been owned by private equity. Today, it claims to make around £7 in every £100 generated for the British economy. In the first half of last year, 60 per cent of the total invested in UK firms via private equity was from abroad.

Many will see this as a success story: British ingenuity attracting international money. Those who worry about foreign investment are seen as misguided and a little jingoistic. The emphasis should be on the investment, rather than worrying that our high streets and infrastructure have been sold off to foreign buyers looking for a good deal.

The reply to these free marketeers can be seen floating down our rivers and in the balance sheets of our creaking water companies. Back in 1991, water firms had a debt-to-equity ratio of 4 per cent. Today it’s around 70 per cent, with some firms having neared 95 per cent. Where did that money go? Clearly not enough of it has been funnelled into infrastructure.

Take Thames Water, which serves a quarter of all British households. In 2006, the utility was bought by a consortium led by the Australian private equity firm the Mac-quarie Group. Over the next 11 years, Thames Water’s debts grew from £3.2 billion to £10 billion, while £2.8 billion was paid out in dividends. Macquarie borrowed against the value of the business – reservoirs, treatments works, even future cash flow – to pay out even more to shareholders.

Thames Water’s parent company became enmeshed in a complex web of intercompany loans and shell structures in places like the Cayman Islands. During the period of Macquarie’s ownership, the company paid just £100,000 in corporation tax. Thames Water is now so heavily indebted, its infrastructure so degraded, that there are serious discussions about renationalisation.

In 1991, water firms had a debt-to-equity ratio of 4 per cent. Today it’s 70 per cent. Where did the money go?

Macquarie defends its behaviour, arguing that they did invest in infrastructure and that Thames Water was never publicly criticised by Ofwat during its tenure. To which one might reply, so much the worse for the regulator. Perhaps that’s why Labour announced this week that they will scrap Ofwat.

As it happens, Macquarie also owned the Hampshire ferry company Wightlink, which under its control saw borrowing increase to pay shareholders, with corresponding timetable reductions, the near doubling of ticket prices and a lack of investment in ferry upgrades. It’s almost as if Macquarie has a strategy.

Of course, not all private equity works in this way. Some companies really do improve the target firms. Pret A Manger is an obvious example, where Bridgepoint helped Pret expand to hundreds of locations before selling it for five times the purchase price, giving every employee £1,000 in the process.

But plenty of people within the world of high finance have expressed concern about some of the practices of private equity. Luke Johnson, the former chairman of Gail’s and former owner of the Ivy, said that in private equity, ‘attention is not directed towards the common wealth, but enriching the management, buyout partners and their institutional backers. That is the nature of the game. To argue otherwise is bogus’.

The former CEO of one of the largest institutional investors in the US, Theresa Whitmarsh, says she was told by one private equity founder that the industry is ‘a zero-sum game, a blood sport’.

This is because growing a business is much harder than squeezing one. If you don’t plan on holding on to a company for the long term, making money can be devilishly simple. First, identify an undervalued business, one that may have struggled but has hard assets that could be flogged on. Then take out loans of up to 80 or 90 per cent of the value of the target company’s assets. Crucially, load the target company with that debt and make them pay the cost of their own acquisition. Next, send in your partners, who will either try to juice the company’s income or slash spending, all while charging fees for these services.

Within the first two years of a public-to-private equity takeover, around 13 per cent of the workforce tends to be laid off. Expert negotiators are brought in to bid down suppliers and assets are sold. There is a laser-like focus on shifting the balance sheet: spend less, earn more, cash in what you can. Never mind the fact that a lack of investment will create problems down the line, that staff turnover rises as wages are squeezed and suppliers abandon the company. Such problems are for the next owner to discover.

Private equity is reaching ever deeper into British life. Take the village of Little-bredy in Dorset. It was recently acquired wholesale by a firm called Belport, which bought all 32 properties in the village from Sir Philip Williams, whose family had owned it for seven generations. One resident who had lived in Littlebredy for 21 years was evicted to make way for an office, while part of the village has been closed to public access. Belport insists that rumours of a mass eviction in January are incorrect. But no one is quite sure what they plan on doing with the estate. Perhaps the village will be turned into a private members’ club like Soho Farmhouse, or maybe it’ll become a high-end holiday park or wedding venue. When private equity comes to town, every asset is sweated for all its worth.

It’s strange to see an English village bought up in the name of shareholder value. But things get much stranger when we look at unloved parts of the British state. The number of children’s care homes that are operated by private equity has more than doubled over the past five years. Many of the larger operators have profits in the tens of millions of pounds and margins sit at more than 20 per cent. According to the Local Government Association, children’s care homes are charging the taxpayer as much as an annual £3.2 million per child – and fees are growing well above inflation. Meanwhile, many local authorities are themselves close to bankruptcy as they scrabble to pay for these services. An independent review into the sector recently found that ‘there are few indicators to suggest that high prices are leading to better quality homes for children’.

In many private equity-run care homes, everything is cut to within an inch of what regulations allow

Local councils are legally bound to ensure that children with serious disabilities and those without parents are looked after. Most of the time, councils meet these obligations by outsourcing. That means costs can be locked in for the length of the contracts, which makes cash flow easier for local authorities to manage. But it also gives civil servants plausible deniability. When something goes wrong, they can point to the private company and shift the blame. And the likelihood of something going wrong is much higher with private equity, because the portfolio companies are highly leveraged. For every £1 in debt these children’s homes are, there’s just 5p of cash flow for debt servicing. For non-private-equity homes, that figure is around 40p.

This is exactly how private equity is supposed to work – spare cash is a form of inefficiency. So instead that money is redeployed or used to pay shareholders. The problems come with economic uncertainty, when rates spike or credit availability shrinks.

It’s a pattern we see repeated again and again. Southern Cross, a care group for the elderly, collapsed in 2011. Its previous owners, Blackstone, the largest private equity firm in the world, had performed a classic industry trick: sell off the properties, then lease them back and pocket the difference. (Morrisons’ new owners are currently using this sale and leaseback strategy having said during the buyout that they wouldn’t.) Meanwhile, Blackstone expanded the group through debt finance. When the 2008 crash came, social care budgets were squeezed and Southern Cross was unable to repay its debts. Blackstone had already cashed out, making £500 million in the process, while 31,000 residents were thrown into limbo. The group was broken up and sold off, with councils footing the bill for higher operating fees and transition costs.

In many private-equity-run care homes, everything is cut to within an inch of what regulations allow. Workers are kept on minimum wage or brought in from agencies, and the staff-to-residents ratio is kept as low as is permitted. Food is purchased in bulk and for the lowest possible price while maintenance on buildings is deferred. A study in the United States found that care homes owned by private equity have a mortality rate 10 per cent higher than those managed by medical professionals.

Private equity firms tend to have large and diverse portfolios, meaning that expertise doesn’t necessarily translate across the different companies they own. Knowing how to run an efficient biscuit factory doesn’t mean you know how to run an efficient chain of veterinary clinics. The one thing that all businesses have to worry about is tax, meaning this tends to be what private equity firms actually focus on. One study found that up to 40 per cent of the savings brought by private equity come from tweaking tax arrangements. The large amounts of debt often helps. Target companies offset the cost of servicing debts against their tax bill. Gatwick Airport didn’t pay a penny in corporation tax for the six years it was owned by private equity, because its buyout loans were tax deductible.

Selling a company isn’t always even necessary to make a profit. When Toys ‘R’ Us filed for bankruptcy, it emerged that the private equity firms which bought it still ended up in the black. They’d charged Toys ‘R’ Us fees that more than recouped the relatively small amount of capital they’d put up for the acquisition. The staff, meanwhile, saw their pension contributions disappear.

Most of the money for acquisitions is paid by institutional investors like pension funds. Repayments to these limited partners are fixed, but the upsides for private equity can be huge. The irony, of course, is that pensions are supposed to create stability for workers. Yet these savings are being used to acquire companies and often cut costs, sometimes even dismantling pension pots.

Take the Yorkshire mattress manufacturer Silentnight. In the late 2000s, the family-run firm was facing cash-flow problems. It found salvation in HIG Europe, an affiliate of the Miami-based private equity firm HIG Capital. This gave Silentnight a line of credit, allowing the company to weather the effects of the 2008 recession. That was, until HIG suddenly removed it, demanding the debt be repaid. Within days, Silentnight went into administration and was snapped up by HIG.

It’s a classic example of what’s known as loan-to-own. In the process, the private equity firm jettisoned the company’s hefty pensions obligations. Instead, the state-run emergency Pension Protection Fund had to pick up the tab, suddenly making Silentnight an attractive, solvent company once again. The regulator twice accused HIG of engineering an unnecessary insolvency in order to shift pensions on to the public purse. Eventually, after more than a decade, HIG settled for £25 million but did not accept any liability. Staff pensions had been cut by a third, the equivalent of £50 million. HIG was still quids in. Perversely, the state-run Pension Protection Fund is a major investor in private equity firms, some of whom have been accused of offshoring profits to avoid tax.

No one could object to genuine investment, but this type of business practice gives capitalism a bad name. In Britain’s desperation for foreign money, we’ve invited in a whole class of savvy corporate raiders who know how to loot UK Plc – and get away with it. The result is that we’ve been left, quite literally, in the shit.

Comments