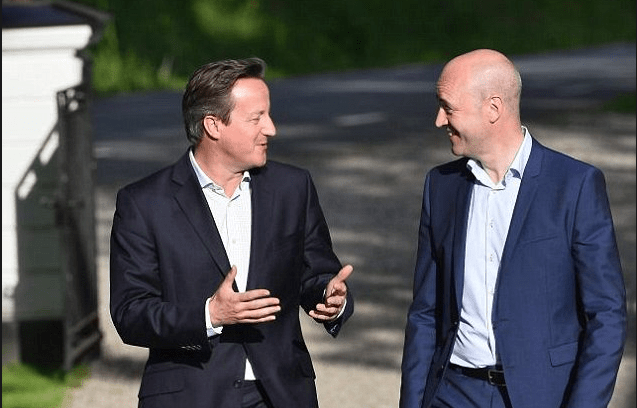

A modernising, young Prime Minister advocates free schools, cuts taxes and oversees a job creation miracle – could voters really kick him out? It happened in Sweden six months ago when Fredrik Reinfeldt lost the general election, even though his successor failed to win a majority. Earlier this year, I caught up with Reinfeldt to talk to him about politics – and the problems of converting economic success into political capital

His defenestration seemed horribly unfair. While much of Europe was in economic agony, Sweden was not: at the time, if you asked about the recession you were met with a blank stare. To an outsider visiting Sweden, its economic recovery was extraordinary. But to Swedes, it was rather boring.

Speaking in an office next to the Swedish parliament, Reinfeldt says his party fell victim to the paradox of success. “It was a feel-good factor that took attention away from issues that are important for my party [ie, the economy].” Voters, he says, instead argued: “Well, I have a good life. So now, I worry about reports that other people have problems in healthcare.” It’s the great problem of conservatism: if you fix the economy, you’re not thanked. Voters simply worry about other things.

So it is in Britain – as the economy has recovered, concern about it has fallen. As Britain goes to the polls, this is the problem Cameron faces: his Chancellor, George Osborne, wanted to campaign on the economy thinking that its recovery could be converted into re-election. Instead, economic success has led to declining interest in the economy. Concern about health and immigration has risen, two issues where Labour and Ukip do best respectively.

[datawrapper chart=”http://static.spectator.co.uk/s6e0x/index.html”]

But before Reinfeldt’s defeat came became the first conservative in Swedish history to be re-elected. He cutting taxes so much that he was able to say the low-waged worker had, in effect, been given an extra month’s salary every year (in Britain, Tories say that 27 million have had tax cuts. But it adds up to about ten days extra pay in every year, barely enough to overcome the cost of the VAT rises). When then crash came, Reinfeldt’s ‘stimulus’ was a permanent tax cut rather than bailouts, or debt-fuelled spending. His tax cuts were targeted using tax credits, rather than the blunter tool of raising everyone’s tax threshold. As work paid significantly more, far more Swedes chose to work. The extra workers meant extra tax, and the tax cut paid for itself.

After eight years in office, much of Reinfeldt’s tax-cutting work was done. “A lot of the taxes that were annoying a lot of Swedes, going back to the nineties, are not there anymore, he said. “Wealth tax has been abandoned. We don’t have an inheritance tax. The property tax that had been annoying a lot of people was taken away. Incomes taxes are quite lower. Corporation tax has been lowered from 28 per cent down to 22 per cent. Tax deductions that for home care, work assistance – everything is now in place.”

So by the end of his second term, it was hard to come up with a follow-up act. “Something happens when you have actually ticked off all the agenda points, when you have taken away the taxes that annoyed people. They don’t have anything to get annoyed about any more. Unless the Left [the current government coalition] reintroduce these taxes, we solved the basic problems.” When he came into government, Sweden’s tax-GDP ratio was 52 per cent, one of the highest in the world. He had a bet with Borg to see if he could lower it to 45 by the time he turned 45. He succeeded.

“Sweden’s tax/GDP ratio is actually down to about 42 per cent…. most of the tax cuts we have done they do not dare to change.” This is where he differs from Cameron: to Reinfeldt, such figures matter a lot. Cameron, if asked, would probably not know what the British figure is. Reinfeldt is a man of detail and business, who managed to sell his radicalism to the Swedish public by making it sound quite dull. In Britain and America, tax-cutting Conservatives like to pose as radicals – as Thatcher and Nigel Lawson did during the high political drama of the 1980s. Reinfelt’s innovation was to make radicalism boring.

But no one can make immigration boring. Sweden has absorbed more refugees, per capita, than any other country in Europe with relatively little debate. The subject is so sensitive in Sweden as to be virtually a taboo amongst its mainstream parties. Sweden prides itself on its openness – a national characteristic that I have personal reason to be grateful for. In the late 1960s it granted asylum to Czechs fleeing the Soviets after the Prague Spring. My wife’s parents were amongst them. They arrived penniless in Stockholm and were given everything: tuition in Swedish, help with resettlement. Sweden’s openness is a stand-out characteristic of the country, and one in which most Swedes take tremendous pride.

This reputation has made Sweden a magnet for immigrants – as in Britain, far more arrived than were expected. In the last few years this has included Romanians, most of whom come to work. But a minority have found that Sweden’s openness extends to tolerating organised begging, in the streets and the underground, and even allowing immigrants to pitch tents in the main streets and store their belongings in massive piles in the city centre during the day. All of this sends a dangerous message: that the Swedish authorities have lost control of immigration. Over time, it has eroded the famous tolerance that Sweden’s approach to immigration had been built upon.

Speaking in an office next to the Swedish parliament, Reinfeldt says his party fell victim to the paradox of success. “It was a feel-good factor that took attention away from issues that are important for my party [ie, the economy].” Voters, he says, instead argued: “Well, I have a good life. So now, I worry about reports that other people have problems in healthcare.” It’s the great problem of conservatism: if you fix the economy, you’re not thanked. Voters simply worry about other things.

So it is in Britain – as the economy has recovered, concern about it has fallen. As Britain goes to the polls, this is the problem Cameron faces: his Chancellor, George Osborne, wanted to campaign on the economy thinking that its recovery could be converted into re-election. Instead, economic success has led to declining interest in the economy. Concern about health and immigration has risen, two issues where Labour and Ukip do best respectively.

[datawrapper chart=”http://static.spectator.co.uk/s6e0x/index.html”]

But before Reinfeldt’s defeat came became the first conservative in Swedish history to be re-elected. He cutting taxes so much that he was able to say the low-waged worker had, in effect, been given an extra month’s salary every year (in Britain, Tories say that 27 million have had tax cuts. But it adds up to about ten days extra pay in every year, barely enough to overcome the cost of the VAT rises). When then crash came, Reinfeldt’s ‘stimulus’ was a permanent tax cut rather than bailouts, or debt-fuelled spending. His tax cuts were targeted using tax credits, rather than the blunter tool of raising everyone’s tax threshold. As work paid significantly more, far more Swedes chose to work. The extra workers meant extra tax, and the tax cut paid for itself.

After eight years in office, much of Reinfeldt’s tax-cutting work was done. “A lot of the taxes that were annoying a lot of Swedes, going back to the nineties, are not there anymore, he said. “Wealth tax has been abandoned. We don’t have an inheritance tax. The property tax that had been annoying a lot of people was taken away. Incomes taxes are quite lower. Corporation tax has been lowered from 28 per cent down to 22 per cent. Tax deductions that for home care, work assistance – everything is now in place.”

So by the end of his second term, it was hard to come up with a follow-up act. “Something happens when you have actually ticked off all the agenda points, when you have taken away the taxes that annoyed people. They don’t have anything to get annoyed about any more. Unless the Left [the current government coalition] reintroduce these taxes, we solved the basic problems.” When he came into government, Sweden’s tax-GDP ratio was 52 per cent, one of the highest in the world. He had a bet with Borg to see if he could lower it to 45 by the time he turned 45. He succeeded.

“Sweden’s tax/GDP ratio is actually down to about 42 per cent…. most of the tax cuts we have done they do not dare to change.” This is where he differs from Cameron: to Reinfeldt, such figures matter a lot. Cameron, if asked, would probably not know what the British figure is. Reinfeldt is a man of detail and business, who managed to sell his radicalism to the Swedish public by making it sound quite dull. In Britain and America, tax-cutting Conservatives like to pose as radicals – as Thatcher and Nigel Lawson did during the high political drama of the 1980s. Reinfelt’s innovation was to make radicalism boring.

But no one can make immigration boring. Sweden has absorbed more refugees, per capita, than any other country in Europe with relatively little debate. The subject is so sensitive in Sweden as to be virtually a taboo amongst its mainstream parties. Sweden prides itself on its openness – a national characteristic that I have personal reason to be grateful for. In the late 1960s it granted asylum to Czechs fleeing the Soviets after the Prague Spring. My wife’s parents were amongst them. They arrived penniless in Stockholm and were given everything: tuition in Swedish, help with resettlement. Sweden’s openness is a stand-out characteristic of the country, and one in which most Swedes take tremendous pride.

This reputation has made Sweden a magnet for immigrants – as in Britain, far more arrived than were expected. In the last few years this has included Romanians, most of whom come to work. But a minority have found that Sweden’s openness extends to tolerating organised begging, in the streets and the underground, and even allowing immigrants to pitch tents in the main streets and store their belongings in massive piles in the city centre during the day. All of this sends a dangerous message: that the Swedish authorities have lost control of immigration. Over time, it has eroded the famous tolerance that Sweden’s approach to immigration had been built upon.

Polls show 71 per cent of Swedes want an end to the organised begging which is starting to change the face of Stockholm. Yet only last week, the Swedish parliament resolved not to act.

When mainstream parties do not listen to, or reflect public concern this creates the space for a new party – and it has came in the form of the Sweden Democrats, an unpleasant version of Ukip, who took 13 per cent of the vote. The surprise post-election departure of its leader, Jimmie Åkesson (he signed off ill, with stress), has not dampened its support – the latest polls show the Sweden Democrats edging closer to 18 per cent.

“Every party that wins new voters find some kind of energy, some kind of missed agenda,” says Reinfeldt. “That’s always the case.” But to him, and other party leaders, adopting a more robust line on immigration would have represented a concession to the Sweden Democrats. And would have brought swift censure from the Swedish media, who exert a surprisingly strong influence over its politicians. But it was personal conviction, rather than media pressure, that led Reinfeldt to delivered a speech during the campaign where he urged Swedes to “open your hearts” to immigration. It was brave, sincere – but was, perhaps, the exact opposite of what he should be doing to win back voters considering the Sweden Democrats.

So here is a fairly typical story of political downfall. Reinfeldt and Borg had a strong economic policy, but lost power once voters’ attention started to turn to something else. But in general, Reinfeldt says, it’s the curse of power. He argues that conservatives need to keep renewing for an ever-changing world – hard in opposition, but even harder if you get elected and end up bogged down with government. He and Cameron both started reform their parties in opposition – “a totally different task from trying to renew during government. That’s much tougher because you have everyday responsibilities. At the same time, you’re trying to say: we are also moving and developing as a party. I found that to be a very different, much tougher task than actually to formulate this in opposition.”

In power, he says, you worry about your own policies. But to renew and adapt, a party needs to respond to someone else’s agenda. “You have to adapt to a change, to an agenda which comes from outside.”

Borg is already living abroad and recently left his wife for a member of Army of Lovers, a pop group that once sought to be Sweden Eurovision’s entry (it’s quite an army: one of its other members is rumoured to have had an affair with Sweden’s king). Reinfeldt is not planning anything so dramatic: he’ll stay in Stockholm working on his book. And then, perhaps, talking some more about what he demonstrated – but so many on Europe refused to believe – that lowering taxes can help employment and stoke recoveries.

“If you actually can create jobs, a strong economy, then you create a stronger society. I think that’s my legacy; that’s what I’m going to work with. Britain is also an interesting example of job creation and it’s also heading in a very good direction.” Economically, he’s right – Britain has followed his example, step-by-step. We will find out tomorrow whether, as a result, Cameron will become a other 49-year-old writing memoirs and joining the ex-Prime Ministers club.

Polls show 71 per cent of Swedes want an end to the organised begging which is starting to change the face of Stockholm. Yet only last week, the Swedish parliament resolved not to act.

When mainstream parties do not listen to, or reflect public concern this creates the space for a new party – and it has came in the form of the Sweden Democrats, an unpleasant version of Ukip, who took 13 per cent of the vote. The surprise post-election departure of its leader, Jimmie Åkesson (he signed off ill, with stress), has not dampened its support – the latest polls show the Sweden Democrats edging closer to 18 per cent.

“Every party that wins new voters find some kind of energy, some kind of missed agenda,” says Reinfeldt. “That’s always the case.” But to him, and other party leaders, adopting a more robust line on immigration would have represented a concession to the Sweden Democrats. And would have brought swift censure from the Swedish media, who exert a surprisingly strong influence over its politicians. But it was personal conviction, rather than media pressure, that led Reinfeldt to delivered a speech during the campaign where he urged Swedes to “open your hearts” to immigration. It was brave, sincere – but was, perhaps, the exact opposite of what he should be doing to win back voters considering the Sweden Democrats.

So here is a fairly typical story of political downfall. Reinfeldt and Borg had a strong economic policy, but lost power once voters’ attention started to turn to something else. But in general, Reinfeldt says, it’s the curse of power. He argues that conservatives need to keep renewing for an ever-changing world – hard in opposition, but even harder if you get elected and end up bogged down with government. He and Cameron both started reform their parties in opposition – “a totally different task from trying to renew during government. That’s much tougher because you have everyday responsibilities. At the same time, you’re trying to say: we are also moving and developing as a party. I found that to be a very different, much tougher task than actually to formulate this in opposition.”

In power, he says, you worry about your own policies. But to renew and adapt, a party needs to respond to someone else’s agenda. “You have to adapt to a change, to an agenda which comes from outside.”

Borg is already living abroad and recently left his wife for a member of Army of Lovers, a pop group that once sought to be Sweden Eurovision’s entry (it’s quite an army: one of its other members is rumoured to have had an affair with Sweden’s king). Reinfeldt is not planning anything so dramatic: he’ll stay in Stockholm working on his book. And then, perhaps, talking some more about what he demonstrated – but so many on Europe refused to believe – that lowering taxes can help employment and stoke recoveries.

“If you actually can create jobs, a strong economy, then you create a stronger society. I think that’s my legacy; that’s what I’m going to work with. Britain is also an interesting example of job creation and it’s also heading in a very good direction.” Economically, he’s right – Britain has followed his example, step-by-step. We will find out tomorrow whether, as a result, Cameron will become a other 49-year-old writing memoirs and joining the ex-Prime Ministers club.

Speaking in an office next to the Swedish parliament, Reinfeldt says his party fell victim to the paradox of success. “It was a feel-good factor that took attention away from issues that are important for my party [ie, the economy].” Voters, he says, instead argued: “Well, I have a good life. So now, I worry about reports that other people have problems in healthcare.” It’s the great problem of conservatism: if you fix the economy, you’re not thanked. Voters simply worry about other things.

So it is in Britain – as the economy has recovered, concern about it has fallen. As Britain goes to the polls, this is the problem Cameron faces: his Chancellor, George Osborne, wanted to campaign on the economy thinking that its recovery could be converted into re-election. Instead, economic success has led to declining interest in the economy. Concern about health and immigration has risen, two issues where Labour and Ukip do best respectively.

[datawrapper chart=”http://static.spectator.co.uk/s6e0x/index.html”]

But before Reinfeldt’s defeat came became the first conservative in Swedish history to be re-elected. He cutting taxes so much that he was able to say the low-waged worker had, in effect, been given an extra month’s salary every year (in Britain, Tories say that 27 million have had tax cuts. But it adds up to about ten days extra pay in every year, barely enough to overcome the cost of the VAT rises). When then crash came, Reinfeldt’s ‘stimulus’ was a permanent tax cut rather than bailouts, or debt-fuelled spending. His tax cuts were targeted using tax credits, rather than the blunter tool of raising everyone’s tax threshold. As work paid significantly more, far more Swedes chose to work. The extra workers meant extra tax, and the tax cut paid for itself.

After eight years in office, much of Reinfeldt’s tax-cutting work was done. “A lot of the taxes that were annoying a lot of Swedes, going back to the nineties, are not there anymore, he said. “Wealth tax has been abandoned. We don’t have an inheritance tax. The property tax that had been annoying a lot of people was taken away. Incomes taxes are quite lower. Corporation tax has been lowered from 28 per cent down to 22 per cent. Tax deductions that for home care, work assistance – everything is now in place.”

So by the end of his second term, it was hard to come up with a follow-up act. “Something happens when you have actually ticked off all the agenda points, when you have taken away the taxes that annoyed people. They don’t have anything to get annoyed about any more. Unless the Left [the current government coalition] reintroduce these taxes, we solved the basic problems.” When he came into government, Sweden’s tax-GDP ratio was 52 per cent, one of the highest in the world. He had a bet with Borg to see if he could lower it to 45 by the time he turned 45. He succeeded.

“Sweden’s tax/GDP ratio is actually down to about 42 per cent…. most of the tax cuts we have done they do not dare to change.” This is where he differs from Cameron: to Reinfeldt, such figures matter a lot. Cameron, if asked, would probably not know what the British figure is. Reinfeldt is a man of detail and business, who managed to sell his radicalism to the Swedish public by making it sound quite dull. In Britain and America, tax-cutting Conservatives like to pose as radicals – as Thatcher and Nigel Lawson did during the high political drama of the 1980s. Reinfelt’s innovation was to make radicalism boring.

But no one can make immigration boring. Sweden has absorbed more refugees, per capita, than any other country in Europe with relatively little debate. The subject is so sensitive in Sweden as to be virtually a taboo amongst its mainstream parties. Sweden prides itself on its openness – a national characteristic that I have personal reason to be grateful for. In the late 1960s it granted asylum to Czechs fleeing the Soviets after the Prague Spring. My wife’s parents were amongst them. They arrived penniless in Stockholm and were given everything: tuition in Swedish, help with resettlement. Sweden’s openness is a stand-out characteristic of the country, and one in which most Swedes take tremendous pride.

This reputation has made Sweden a magnet for immigrants – as in Britain, far more arrived than were expected. In the last few years this has included Romanians, most of whom come to work. But a minority have found that Sweden’s openness extends to tolerating organised begging, in the streets and the underground, and even allowing immigrants to pitch tents in the main streets and store their belongings in massive piles in the city centre during the day. All of this sends a dangerous message: that the Swedish authorities have lost control of immigration. Over time, it has eroded the famous tolerance that Sweden’s approach to immigration had been built upon.

Speaking in an office next to the Swedish parliament, Reinfeldt says his party fell victim to the paradox of success. “It was a feel-good factor that took attention away from issues that are important for my party [ie, the economy].” Voters, he says, instead argued: “Well, I have a good life. So now, I worry about reports that other people have problems in healthcare.” It’s the great problem of conservatism: if you fix the economy, you’re not thanked. Voters simply worry about other things.

So it is in Britain – as the economy has recovered, concern about it has fallen. As Britain goes to the polls, this is the problem Cameron faces: his Chancellor, George Osborne, wanted to campaign on the economy thinking that its recovery could be converted into re-election. Instead, economic success has led to declining interest in the economy. Concern about health and immigration has risen, two issues where Labour and Ukip do best respectively.

[datawrapper chart=”http://static.spectator.co.uk/s6e0x/index.html”]

But before Reinfeldt’s defeat came became the first conservative in Swedish history to be re-elected. He cutting taxes so much that he was able to say the low-waged worker had, in effect, been given an extra month’s salary every year (in Britain, Tories say that 27 million have had tax cuts. But it adds up to about ten days extra pay in every year, barely enough to overcome the cost of the VAT rises). When then crash came, Reinfeldt’s ‘stimulus’ was a permanent tax cut rather than bailouts, or debt-fuelled spending. His tax cuts were targeted using tax credits, rather than the blunter tool of raising everyone’s tax threshold. As work paid significantly more, far more Swedes chose to work. The extra workers meant extra tax, and the tax cut paid for itself.

After eight years in office, much of Reinfeldt’s tax-cutting work was done. “A lot of the taxes that were annoying a lot of Swedes, going back to the nineties, are not there anymore, he said. “Wealth tax has been abandoned. We don’t have an inheritance tax. The property tax that had been annoying a lot of people was taken away. Incomes taxes are quite lower. Corporation tax has been lowered from 28 per cent down to 22 per cent. Tax deductions that for home care, work assistance – everything is now in place.”

So by the end of his second term, it was hard to come up with a follow-up act. “Something happens when you have actually ticked off all the agenda points, when you have taken away the taxes that annoyed people. They don’t have anything to get annoyed about any more. Unless the Left [the current government coalition] reintroduce these taxes, we solved the basic problems.” When he came into government, Sweden’s tax-GDP ratio was 52 per cent, one of the highest in the world. He had a bet with Borg to see if he could lower it to 45 by the time he turned 45. He succeeded.

“Sweden’s tax/GDP ratio is actually down to about 42 per cent…. most of the tax cuts we have done they do not dare to change.” This is where he differs from Cameron: to Reinfeldt, such figures matter a lot. Cameron, if asked, would probably not know what the British figure is. Reinfeldt is a man of detail and business, who managed to sell his radicalism to the Swedish public by making it sound quite dull. In Britain and America, tax-cutting Conservatives like to pose as radicals – as Thatcher and Nigel Lawson did during the high political drama of the 1980s. Reinfelt’s innovation was to make radicalism boring.

But no one can make immigration boring. Sweden has absorbed more refugees, per capita, than any other country in Europe with relatively little debate. The subject is so sensitive in Sweden as to be virtually a taboo amongst its mainstream parties. Sweden prides itself on its openness – a national characteristic that I have personal reason to be grateful for. In the late 1960s it granted asylum to Czechs fleeing the Soviets after the Prague Spring. My wife’s parents were amongst them. They arrived penniless in Stockholm and were given everything: tuition in Swedish, help with resettlement. Sweden’s openness is a stand-out characteristic of the country, and one in which most Swedes take tremendous pride.

This reputation has made Sweden a magnet for immigrants – as in Britain, far more arrived than were expected. In the last few years this has included Romanians, most of whom come to work. But a minority have found that Sweden’s openness extends to tolerating organised begging, in the streets and the underground, and even allowing immigrants to pitch tents in the main streets and store their belongings in massive piles in the city centre during the day. All of this sends a dangerous message: that the Swedish authorities have lost control of immigration. Over time, it has eroded the famous tolerance that Sweden’s approach to immigration had been built upon.

Polls show 71 per cent of Swedes want an end to the organised begging which is starting to change the face of Stockholm. Yet only last week, the Swedish parliament resolved not to act.

When mainstream parties do not listen to, or reflect public concern this creates the space for a new party – and it has came in the form of the Sweden Democrats, an unpleasant version of Ukip, who took 13 per cent of the vote. The surprise post-election departure of its leader, Jimmie Åkesson (he signed off ill, with stress), has not dampened its support – the latest polls show the Sweden Democrats edging closer to 18 per cent.

“Every party that wins new voters find some kind of energy, some kind of missed agenda,” says Reinfeldt. “That’s always the case.” But to him, and other party leaders, adopting a more robust line on immigration would have represented a concession to the Sweden Democrats. And would have brought swift censure from the Swedish media, who exert a surprisingly strong influence over its politicians. But it was personal conviction, rather than media pressure, that led Reinfeldt to delivered a speech during the campaign where he urged Swedes to “open your hearts” to immigration. It was brave, sincere – but was, perhaps, the exact opposite of what he should be doing to win back voters considering the Sweden Democrats.

So here is a fairly typical story of political downfall. Reinfeldt and Borg had a strong economic policy, but lost power once voters’ attention started to turn to something else. But in general, Reinfeldt says, it’s the curse of power. He argues that conservatives need to keep renewing for an ever-changing world – hard in opposition, but even harder if you get elected and end up bogged down with government. He and Cameron both started reform their parties in opposition – “a totally different task from trying to renew during government. That’s much tougher because you have everyday responsibilities. At the same time, you’re trying to say: we are also moving and developing as a party. I found that to be a very different, much tougher task than actually to formulate this in opposition.”

In power, he says, you worry about your own policies. But to renew and adapt, a party needs to respond to someone else’s agenda. “You have to adapt to a change, to an agenda which comes from outside.”

Borg is already living abroad and recently left his wife for a member of Army of Lovers, a pop group that once sought to be Sweden Eurovision’s entry (it’s quite an army: one of its other members is rumoured to have had an affair with Sweden’s king). Reinfeldt is not planning anything so dramatic: he’ll stay in Stockholm working on his book. And then, perhaps, talking some more about what he demonstrated – but so many on Europe refused to believe – that lowering taxes can help employment and stoke recoveries.

“If you actually can create jobs, a strong economy, then you create a stronger society. I think that’s my legacy; that’s what I’m going to work with. Britain is also an interesting example of job creation and it’s also heading in a very good direction.” Economically, he’s right – Britain has followed his example, step-by-step. We will find out tomorrow whether, as a result, Cameron will become a other 49-year-old writing memoirs and joining the ex-Prime Ministers club.

Polls show 71 per cent of Swedes want an end to the organised begging which is starting to change the face of Stockholm. Yet only last week, the Swedish parliament resolved not to act.

When mainstream parties do not listen to, or reflect public concern this creates the space for a new party – and it has came in the form of the Sweden Democrats, an unpleasant version of Ukip, who took 13 per cent of the vote. The surprise post-election departure of its leader, Jimmie Åkesson (he signed off ill, with stress), has not dampened its support – the latest polls show the Sweden Democrats edging closer to 18 per cent.

“Every party that wins new voters find some kind of energy, some kind of missed agenda,” says Reinfeldt. “That’s always the case.” But to him, and other party leaders, adopting a more robust line on immigration would have represented a concession to the Sweden Democrats. And would have brought swift censure from the Swedish media, who exert a surprisingly strong influence over its politicians. But it was personal conviction, rather than media pressure, that led Reinfeldt to delivered a speech during the campaign where he urged Swedes to “open your hearts” to immigration. It was brave, sincere – but was, perhaps, the exact opposite of what he should be doing to win back voters considering the Sweden Democrats.

So here is a fairly typical story of political downfall. Reinfeldt and Borg had a strong economic policy, but lost power once voters’ attention started to turn to something else. But in general, Reinfeldt says, it’s the curse of power. He argues that conservatives need to keep renewing for an ever-changing world – hard in opposition, but even harder if you get elected and end up bogged down with government. He and Cameron both started reform their parties in opposition – “a totally different task from trying to renew during government. That’s much tougher because you have everyday responsibilities. At the same time, you’re trying to say: we are also moving and developing as a party. I found that to be a very different, much tougher task than actually to formulate this in opposition.”

In power, he says, you worry about your own policies. But to renew and adapt, a party needs to respond to someone else’s agenda. “You have to adapt to a change, to an agenda which comes from outside.”

Borg is already living abroad and recently left his wife for a member of Army of Lovers, a pop group that once sought to be Sweden Eurovision’s entry (it’s quite an army: one of its other members is rumoured to have had an affair with Sweden’s king). Reinfeldt is not planning anything so dramatic: he’ll stay in Stockholm working on his book. And then, perhaps, talking some more about what he demonstrated – but so many on Europe refused to believe – that lowering taxes can help employment and stoke recoveries.

“If you actually can create jobs, a strong economy, then you create a stronger society. I think that’s my legacy; that’s what I’m going to work with. Britain is also an interesting example of job creation and it’s also heading in a very good direction.” Economically, he’s right – Britain has followed his example, step-by-step. We will find out tomorrow whether, as a result, Cameron will become a other 49-year-old writing memoirs and joining the ex-Prime Ministers club.

Comments