A spoon may seem too homely for grand ceremony. It might even, in this sceptical and utilitarian age, seem slightly ridiculous. This prompts the question of how, or whether, we value ancient traditions and ceremonies whose original meanings and power are largely lost to us. And if we do value them, why?

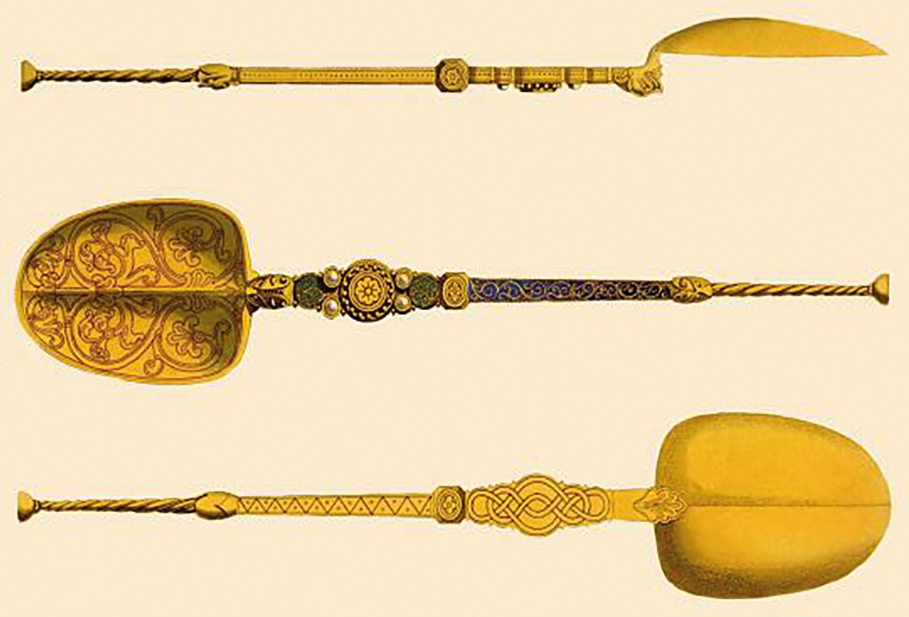

This particular spoon, undeniably, is a very special one: doubtless the world’s most important spoon, and certainly one of the most beautiful examples of that humble genus: silver-gilt, finely engraved with acanthus scrolls, decorated with pearls, and with its bowl strangely divided into two. It dates from the 12th century, and may have been used ever since Richard the Lionheart. It is the oldest piece of the coronation regalia.

After the Civil War the new republic melted everything down. The spoon alone was saved by a Mr Kinnersley, who bought it for 16 shillings – £3,000 today – and presented it to the restored Charles II. It holds the oil that anoints each sovereign (hence the divided bowl, for the archbishop’s two fingers), re-enacting the Biblical anointing of King Solomon by Zadok the Priest, in the ancient belief that monarchs were sacred and ruled in God’s name. France’s kings, indeed, enjoyed chrism brought down from heaven itself by a dove in the year 496 and used, wars and revolutions notwithstanding, until King Charles X in 1825. For King Charles III, the oil comes from olives in the Holy Land, consecrated by the Patriarch of Jerusalem and its Anglican archbishop.

Such mysticism has not always been taken seriously. Following two revolutions, the Calvinist William of Orange, one of our greatest kings, dismissed his coronation in 1689 as ‘funny old popish rites’. Generations of Whigs, dissenters and the left would have agreed. Our late Queen, of course, took it seriously, as now, it seems, does King Charles.

How does our literally disenchanted age respond to a golden spoon of holy oil? Many will be as dismissive as King William. Pious souls will regard it as reverently as the King himself does. Others, including me, will willingly suspend our disbelief. As Walter Bagehot put it in his classic study of the constitution, the monarchy ‘consecrates our whole state’; the spoonful of oil does so literally. Consecrated by God, or by the will of the people, or by the drama of history?

Whichever we choose to believe, it renews what Edmund Burke saw as a perpetual contract between the dead, the living and the yet unborn. This imagined community of nationhood, if it is to survive and flourish, must be what the late Roger Scruton called ‘the inherited first person plural’ – something that over the past few years we have come perilously close to losing.

The coronation ceremony, with all its mysteries and oddities, dates back before the Norman Conquest, and it is something that we can all – however diverse our backgrounds – choose to accept and celebrate as above and beyond our present discontents. If we wish our nation to be more than ‘UK plc’ or a chaos of resentful factions, we should welcome the thought that at its heart is something ancient, unique, even sacred. Not to be deified, but to be respected and cherished. As the choir sings Handel’s anthem Zadok the Priest (‘And all the people rejoiced…’) the humble spoon will perform for perhaps the 13th time its mystical function.

Join The Spectator's Fraser Nelson, Katy Balls and guest Camilla Tominey from the Daily Telegraph for a special edition of Coffee House Live covering what kind of monarch Charles III will be, and whether the coronation will distract voters from the Tories’ predicted heavy losses in the local elections. 10 May from 7pm. Book your tickets today: spectator.co.uk/coronation

Comments