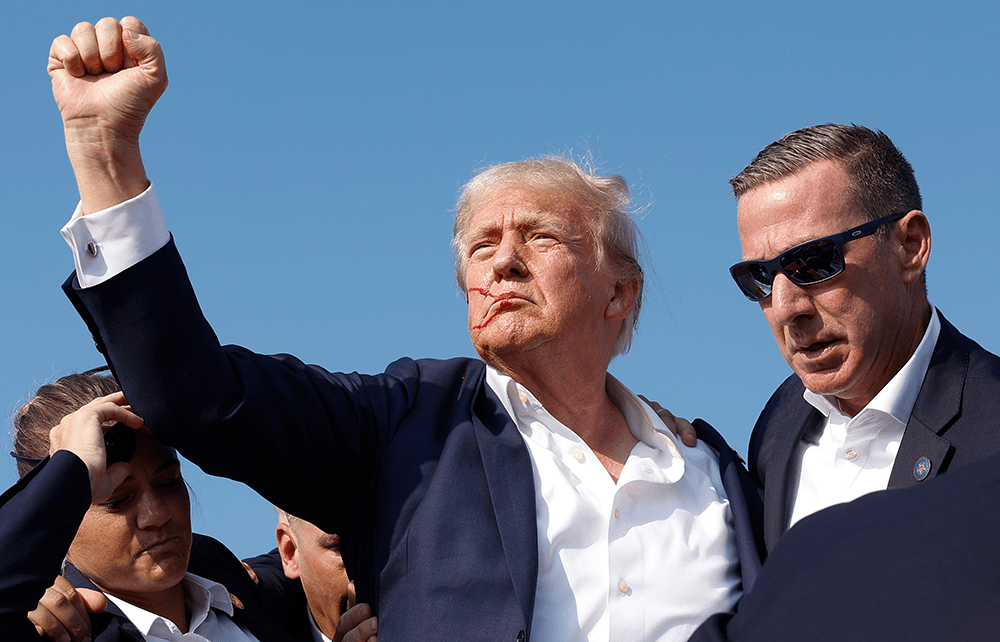

Market reactions to the assassination attempt in Pennsylvania represent, according to taste, rational bets on the significantly increased likelihood of a second Trump presidency or stark confirmation of the madness that has overtaken America and threatens the civilised world.

Shares in Trump Media & Technology – the parent of his social media platform Truth Social – rose by 30 per cent on Monday, adding more than $1 billion to Trump’s notional fortune despite the company’s revenues being, as one observer pointed out, ‘comparable to that of two Starbucks stores’. Also up were shares in gunmakers such as Smith & Wesson and in private prison operators – and US Treasury bond yields, reflecting fears that Trump will let government debt rip. Down, unsurprisingly, were clean energy stocks.

Then there’s bitcoin, up almost 10 per cent in the past few days on top of a six-month rally that has coincided with Trump’s declared enthusiasm for all things crypto: he’s due to address a bitcoin conference in Nashville next week. And frankly, with the way things are going over there, it’s not hard to see why the virtual safe havens of crypto-world, disconnected from the horrors of reality, must look ever more appealing for Americans whatever their political stripe.

Reactions to the shooting were more phlegmatic in London, the FTSE 100 index opening a fraction down – but with one notable 15 per cent faller. That was the luxury brand Burberry, after a bad quarter, a profit warning and a sudden change of chief executive: how ironic, in a season of endless storms, that the biggest loser should be our most famous raincoat maker.

Fading Aim

But let me get back to business as usual – and highlight yet another fissure in London’s underperforming capital markets. A story of the week that hardly anyone noticed was the decision by Destiny Pharma, a Brighton-based biotech, to de-list from the Aim market for smaller companies and seek private equity support. Destiny needs to fund Phase 3 trials of a nasal gel product designed to help prevent post-operative infections, but its cash reserves are dwindling. Chairman Sir Nigel Rudd – a respected City veteran and long-time personal investor in the company – has said de-listing is Destiny’s ‘only viable option’, the likely alternative being liquidation. Why? Because the Aim market and the broking firms that dominate it are incapable of raising follow-on capital at acceptable cost for companies that are some distance from profit; whereas the private equity arena, rapacious though it may often be, still offers a prospect of ‘patient capital’.

When Aim took off in the mid-1990s (as successor to the smaller Unlisted Securities Market) it was hailed as a progressive addition to the City’s product range. Now, as Destiny joins a queue of promising British ventures seeking to de-list for similar reasons, it’s a fading force. The number of companies listed has diminished by a third since 2015, many leavers falling to take-over bidders taking advantage of low valuations, others citing ‘lack of UK institutional interest’ and heading for New York’s Nasdaq market instead.

Meanwhile, the pipeline of new Aim listings has slowed to a trickle. Attention has focused lately on the failure of the London Stock Exchange to attract international companies of suitable quality to list on its main board. But if we no longer have a fertile public market for smaller companies, and a knowledgeable pool of investors prepared to risk their capital in it, we’re missing a key ingredient in the formula for growth so devoutly sought by incoming Labour ministers. They should take aim at Aim.

Golden wedding

On a lighter note, am I bothered that I wasn’t invited to join the Blairs and the Boris Johnsons at last weekend’s wedding of Anant Ambani and Radhika Merchant in Mumbai? Not really: I had a prior commitment to perform in a Yorkshire church fundraiser. But I worry that Mukesh Ambani, the bridegroom’s father and India’s richest industrialist, has done himself no reputational good by spending so lavishly, the whole extended celebration having reportedly cost him £200 million or more.

Does the scale of the bash really prove ‘India’s growing clout on the global stage’, as the Financial Times suggested, or was it just a private jet ticket for world-class freeloaders? And should Ambani père be more discreet about his multibillion fortune, even in a culture that loves a high-gloss wedding, or is he a splendid role model for India’s aspiring entrepreneur class?

I was once driven in a busload of cynical journalists past Antilia, the Ambani family’s luxurious skyscraper home that looks down on teeming Mumbai from the site of a former orphanage just ten minutes from our next point of interest – which was Dhobi Ghat, the city’s dirt-poor laundry district. A rival industrialist, Ratan Tata, once said of Antilia: ‘That’s what revolutions are made of.’ Though Tata later sought to depersonalise his remark as a general comment on ‘wealth in the larger context of the growing disparity in society’, the Ambani newlyweds might be wise to have themselves papped volunteering at a soup kitchen.

Woebegone song

Lighter still, you’re wondering what I performed for the church fundraiser. Despite a scattering of positive economic signals – 0.4 per cent growth in May, pushing some forecasts above 1 per cent for the full year; agreed house sale numbers up 15 per cent on last year in anticipation of interest rate cuts – it felt right to sing Noël Coward’s ‘Bad Times Are Just Around The Corner’. Google the full lyrics and you’ll see it’s the perfect expression of post-election blues: ‘In Tunbridge Wells you can hear the yells of woebegone bourgeoisie… Whoever our vote elects, we know we’re up the spout, lads, and that’s what England expects.’

Comments