My patient has sepsis. The window for treatment is short; in less than an hour, he could die. In urgent care, the direct line to ambulance control bypasses 999: it lets the call handler know a doctor requires urgent attention for a sick patient. Ten minutes: no response. I’m on a second phone to central dispatch: what is going on? A critical incident has been called; the service is overwhelmed. Finally, after 15 minutes, the phone answers and help is on its way.

Worryingly, this is far from an isolated incident. Last week, it was reported that an ambulance service sent a taxi to a GP practice in Bristol to collect a patient with a broken hip after a nine hour wait. In October, the average NHS response time for a category two (emergency) call rose to 54 minutes; this is more than double the national standard of 18 minutes. Such delays, in situations in which every minute counts, can cost lives. They also raise questions as to whether our emergency services can cope with what is coming this winter.

Such delays, in situations in which every minute counts, can cost lives.

If it can’t, it won’t be for lack of money. The NHS budget was £33 billion when Tony Blair came to power in 1997; it has quadrupled to over £150 billion. The NHS capacity crisis, however, has persisted throughout. General and acute bed numbers fell from 181,000 beds in 1987 to just over 100,000 before the pandemic. Despite the backdrop of a steadily ageing population: the number aged 85 or over is predicted to double in 20 years.

Virtually all health secretaries have faced the repetitive existential crisis with rising winter respiratory pathogens such as flu and now Covid with under-resourced and understaffed capacity. Plan B, blaming GPs and other simple policy approaches, are a distraction to the real problem.

The NHS is busy: on a typical day, 835,000 people visit a GP practice, 50,000 an A&E department and 36,000 patients attend for planned hospital treatment. But the UK remains at the bottom of the European bed league table: Germany, for instance, has three times as many beds relative to its population. As a result, NHS occupancy has often been at unsafe levels; overnight stays regularly exceed 95 per cent in winter.

Initiatives to moderate demand have been tried, but evidence as to their effectiveness is lacking. All too often, these fail. In a systematic review to reduce hospital admissions from nursing homes, for example, the evidence was low-quality; and no interventions were tested twice. Similarly, the evidence for interventions at the end of life to reduce inappropriate hospital bed days is limited.

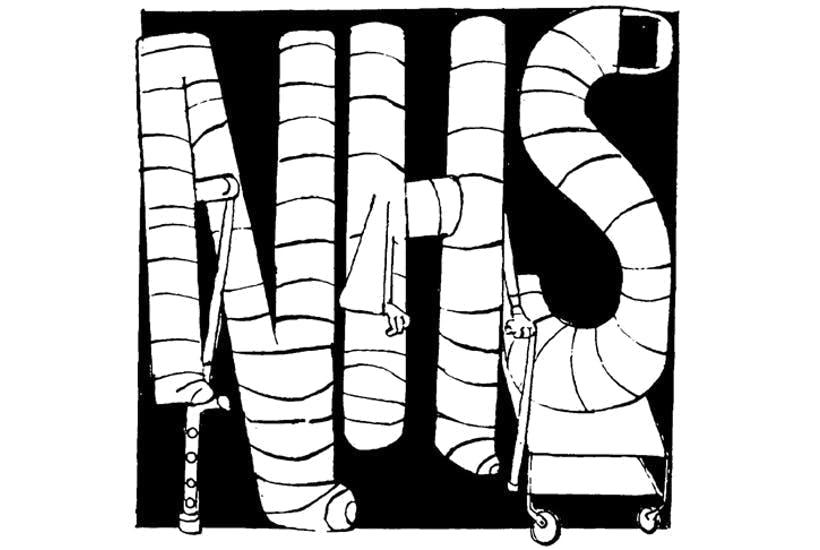

Apparently, the NHS faces the ‘most difficult winter in its history,’ 90 per cent of hospital trust leaders currently feel ‘extremely concerned’. Trusts are reporting they are ‘beyond full stretch’ as they deal with current pressures.

Hospitals cannot operate at 100 per cent demand. Substantial variation in admission occurs by the time of day, the week and the year; the most significant impact occurs at the beginning and end of our lives. Much of this variation is unpredictable. But the winter surge is highly foreseeable.

How can we solve this annual problem? A flexible NHS is needed. One that can provide more resourced beds as demand rises – roughly about 20 per cent to cover the winter surge. These beds need to meet the changing needs of elderly and vulnerable populations who need supportive care that can be lacking in modern super-sized hospitals.

Community hospitals have been around for over 150 years and could assume a more significant role in local healthcare delivery. Randomised trials, for example, have shown that community hospitals can decrease readmissions in older adults with chronic diseases while increasing independence. But there is a need to develop evidence for what works in what setting and what resources are needed. A simple fix, however, is off the table.

A radical rethink is required to ensure evidence is developed so the NHS can protect patients when demand for emergency services rises. The solution involves foresight of the rising demand that occurs at this time of year and a flexible, proactive strategy that removes the need for short term fixes. Anything less than this will mean the NHS continues to be faced each year with a winter surge that could easily overwhelm it.

Comments