John Power has narrated this article for you to listen to.

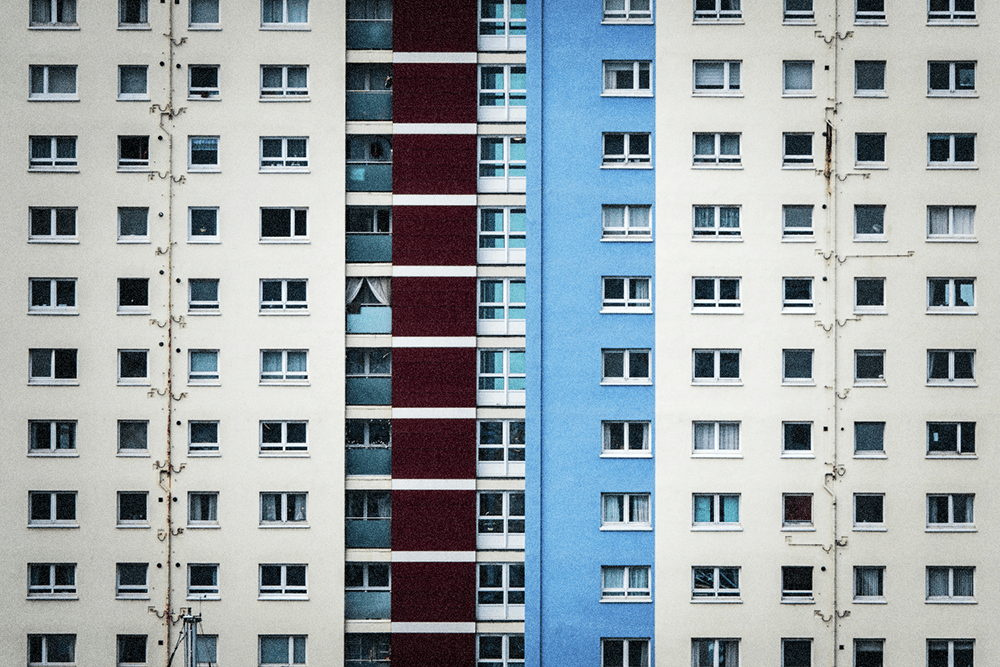

Westminster council has announced that every single social housing tenant in the borough will receive lifetime tenancies. No test of need. No review of income. No incentive to move on. Once you’ve been awarded a property, you can stay as long as you like. When you die, your adult children may be eligible to inherit the lifetime tenancy too.

Social housing tenants in Westminster pay around a fifth of what renters on the open market spend. They also have access to more than one in four properties in the borough, from flats in postwar estates to £1 million terraced houses. The council says it’s bringing stability to people’s lives but for many young professionals dreaming of their own home, it looks like something else: a bribe.

Angela Rayner has secured £39 billion more for social and affordable housing this week. Local councils will use this money not only to build houses, but to buy them from private landlords. It’s a form of class warfare which targets the most politically invisible demographic – young, propertyless professionals – whom the state exploits mercilessly.

One woman told me that she and her partner rent privately on a joint income of more than £100,000, yet still cannot afford to buy in Westminster. ‘We walk past people every day who are being subsidised to live in the middle of London, while we can barely get by,’ she said.

You may scoff at the plight of high-earning professionals, but do the maths: a couple in London on £100,000 loses around £27,000 to tax, £30,000 on rent and 9 per cent of income over £28,000 to student loans before travel and bills. For many professionals, working hard simply doesn’t add up.

They are not alone in feeling this way. Another woman I spoke to recently bought a flat in a converted west London maisonette, only to find Japanese knotweed growing into her garden from a neighbouring property. ‘If I had normal neighbours, this would have been fixed years ago. But because the flat happens to be owned by a housing association, they’re not dealing with it.’ She could lose tens of thousands on the value of her home, while her neighbours don’t face any consequences.

This sense of imbalance is not new, but it’s becoming harder to ignore. One woman found herself living above a man who is fresh out of prison. He was placed there by the local authority and uses the property to deal drugs, smoke weed and house his illegal XL bullies. When she complained, he threatened her with his dogs. When she spoke to the council, she was told the placement was intentional, to keep him away from ‘negative influences’ in a nearby estate.

Voters, paying ever more in housing costs, want a system that also rewards those playing by the rules

Middle-income earners are paying for a model that rewards dysfunction. In the course of reporting this piece, I spoke to a senior housing officer with more than three decades’ experience, a social worker in one of London’s most ethnically segregated boroughs and a former official who has witnessed profound changes in social housing. All spoke of claimants who game the system.

‘People know what to say,’ explained one officer. ‘They’ll allow mould to grow in their temporary accommodation to get on the council flat track. Or say their partner’s become abusive. That gets them priority.’ I was told that some families encourage their daughters to declare themselves homeless while pregnant. ‘Everyone knows how it works,’ one official said. ‘You get her on the list and she’ll get a flat in a couple of years. They’ll take her back in the meantime, then she moves out when a property is offered.’

Once housed, few ever leave. ‘There’s no incentive to move,’ said the social worker. ‘If you start earning, you don’t lose the flat. If you stop, you get help again. People treat it like an inheritance.’ In boroughs such as Tower Hamlets, entire communities have been built around this model. ‘There’s halal butchers, Islamic schools, mosques. The infrastructure is there.’

The patterns are impossible to ignore. In Tower Hamlets, 67 per cent of Muslim households are in social housing. The reasons are complex: economic clustering, migration history, support networks, but the result is visible.

Often newcomers are helped by others who know how the system works. ‘You ask around, someone tells you what to do,’ the former officer said. ‘It’s ingrained.’ Fraud happens too, sometimes spectacularly. In Greenwich, Labour councillor Tonia Ashikodi was convicted of applying for council housing while owning multiple properties. In Tower Hamlets, another Labour councillor and solicitor Muhammad Harun pleaded guilty to housing fraud. Staff across multiple boroughs have been caught taking bribes. But most manipulation is quiet, legal and invisible.

While middle-income Londoners compete with one another in the housing market, the government buys up more properties, removing them from the private rental pool. Westminster council has just spent another £235 million buying hundreds more properties. Those are now off-limits for those looking to rent or buy, pushing up the price of remaining homes. Here, too, are the hidden costs of the groaning social housing system.

‘If you earn £100,000, you lose your child benefit, your tax allowance, your eligibility for support,’ one young professional told me. ‘But the person in the flat next door could be on full housing benefit and you’re paying for them to live there.’ For many, that’s the injustice. The problem isn’t that people are housed, but that they are housed indefinitely, unconditionally and often with more security than those footing the bill.

If we’re serious about fairness, long-term benefit claimants should be rehoused in cheaper areas. This isn’t about punishing those people. In fact, it’s the kinder thing to do: it would free up homes for teachers, nurses, civil servants, people who make cities function and who are priced out.

A new politics may be emerging from this tension. Not one of ideology but of exasperation. Last month, shadow justice secretary Robert Jenrick published a video in which he confronted fare-dodgers on the Tube, asking why they felt they could get for free what everyone else had to pay for. It went viral for a reason. Voters, paying ever more in taxes and housing costs, want a system that also rewards people who play by the rules.

Comments