‘Huw Edwards, Russell Brand, Jermaine Jenas, Phillip Schofield, Gregg Wallace… when will it end?!’ read the message from a friend. Sadly, the answer is that it won’t anytime soon. The media scandals that explode into the headlines – such as those surrounding Gregg Wallace, who is alleged to have made inappropriate comments while working on Masterchef (something he denies) – are met with fury and indignant cries. ‘How was this allowed to happen?’, people ask. But the truth is that these cases are only the tip of the iceberg.

It’s easy to see how the ego of the ‘talent’ can grow to monstrous proportions

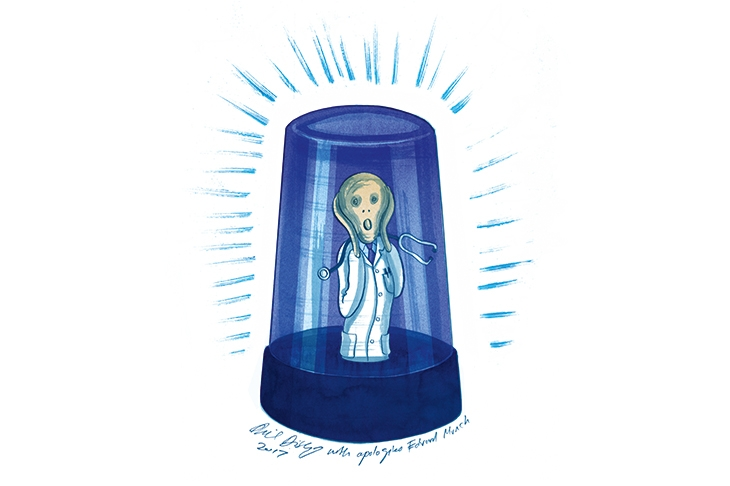

Why is the broadcast media so susceptible to bad behaviour? An unholy trinity of an over-supply of labour, a scarcity of jobs and the monstrous egos of some of the ‘Talent’ – the name given to the most high-profile broadcasters – is to blame.

More people want to work in broadcast roles than ever, but there aren’t enough jobs for them. When people are desperate for work, they put up with bad conditions because they know they are replaceable and lucky to have employment in the first place.

As a result, the tendency – particularly if you’re young and new to the industry – is to suck up the bad bits of the job. You fear that any murmurings of complaint might lead to someone else being chosen for a job next time. I began as a Runner at the BBC back in 2012, and I know this all too well: in addition to exhausting hours and minimal pay, I was made to feel like an utter imbecile on countless occasions. I was screamed at for bringing a director the wrong type of pudding, reduced to tears for hitting the red light and bell on Downton Abbey (used to signal to the full set that the scene was over) when I thought I heard “cut”. No one had, in fact, said “cut”, it was a similar “c” word. I was viciously reprimanded by Taylor Swift’s security for innocently sending a text near her car. I grit my teeth, bit my tongue and kept smiling.

Look at my Instagram account, and you would think that my career since has been a ball. And that is partly true. I have been able to work on some brilliant programmes, with dream guests and wonderful colleagues. A backdrop of gigs and premieres, after-parties and celebrity pals make the lifestyle look glamorous. But social media highlights are misleading. One tends not to take a selfie when slumped over a desk trying hard not to cry after a 17-hour shift.

Perhaps those of us working in TV need to be more honest: lifting the veil on the less appealing parts of the industry might put off some of the idealistic youngsters who have the wrong idea of what a job in broadcast media involves. The Gregg Wallace story should also encourage us to be a bit more open about the industry’s dark underbelly.

BBC director-general Tim Davie recently announced that the corporation will stop calling presenters/ cast/ guests ‘talent’ because it doesn’t help with their godlike status. Davie is on to something: there are so many examples from all the major broadcasters of what happens when the ‘talent’ becomes too big for the show and no one has the nerve to bring them into line. Wallace’s mad response that the complaints were only coming from middle-class women of a certain age – for which he has subsequently apologised – stunk of an ego that has gone unchecked for too long. Of course, it is only those at a more robust stage in their career, those successful enough to be beyond paycheck insecurity, who are in a position to speak out.

It’s easy to see how the ego of the ‘talent’ can grow to monstrous proportions. Producers are encouraged to be ‘charming’, ‘confident’ and ‘highly complimentary’ when dealing with big-name presenters or guests. This tried-and-tested approach not only bolsters the guest’s ego but can lead you to feel complicit should it also bestow any unwanted attention back upon yourself as the producer. I have had multiple interactions that have left me feeling nauseous. Thumbing through the BBC’s Editorial Guidelines in the hope of finding out definitively where the proverbial ‘line’ is and how best to proceed, has provided little salvation. The official guidance is vague and subjective. It is hard to assign fair and comprehensive guidance to cover every interaction with ‘talent’ in the course of producing a programme.

Sexual harassment, bullying and other abuses of power aren’t unique to the media world, but its culture does allow poor behaviour to thrive. There’s pressure, ego and employees willing to endure more than they should have to to keep getting selected for roles.

When things go wrong, calls to HR remain an absolute last resort. All too often, they give the appearance of being there to protect the broadcaster, not the employee. I have ended up regretting almost every single interaction I have had with them. Here is another key part of the problem: when people are either scared to speak up, or see no point in doing so because nothing changes, how will anything improve? Production companies can hide safely behind an individual’s reluctance to formally complain.

So what can be done? Is it too late to require talent to check their ego? Can we stop employing the people we know are problematic? The bosses who have impressed me the most have always been the ones brave enough to say ‘No, XXXX is not coming on this programme’.

People are gradually daring to speak up as they are doing against Gregg Wallace

Another part of the solution would be to cut the number of new entrants into the industry. Doing so could help restore the power imbalance between employers and employees. Employers would then be quicker to bring any inappropriately behaved presenter or guest into line. They would need to ensure the working environment was a pleasant and safe one because there wouldn’t be an endless supply of people rushing to backfill the team.

But if narrowing access was even possible, would it be fair? How can we stop media careers only being options for the affluent or well connected? The lack of diversity is bad enough already.

A further solution would be empowering everyone to speak out, not just those who are in a position where they can weather the storm. But when employment is scarce and the industry small, that isn’t a realistic expectation. It is naive to suggest an individual might be bold enough to take on a corporation or celebrity and not have it impact their career.

So no, perhaps there’s no fast-track to bringing these types of media scandals to an end. If there were any easy fixes, I would like to hope they would have been enacted already. What is required is steady, sustainable and consistent change which takes time. People are gradually daring to speak up as they are doing against Gregg Wallace. There is, of course, safety in numbers. Consideration is being given to how to make policies on bullying and harassment more than just lip service. Executive producers like me are more selective with who we want to work for; that choice often comes down to how a company or its fronting ‘talent’ treat the person with the lowest status in the room. That person was once me. I remember it clearly. It wasn’t that long ago.