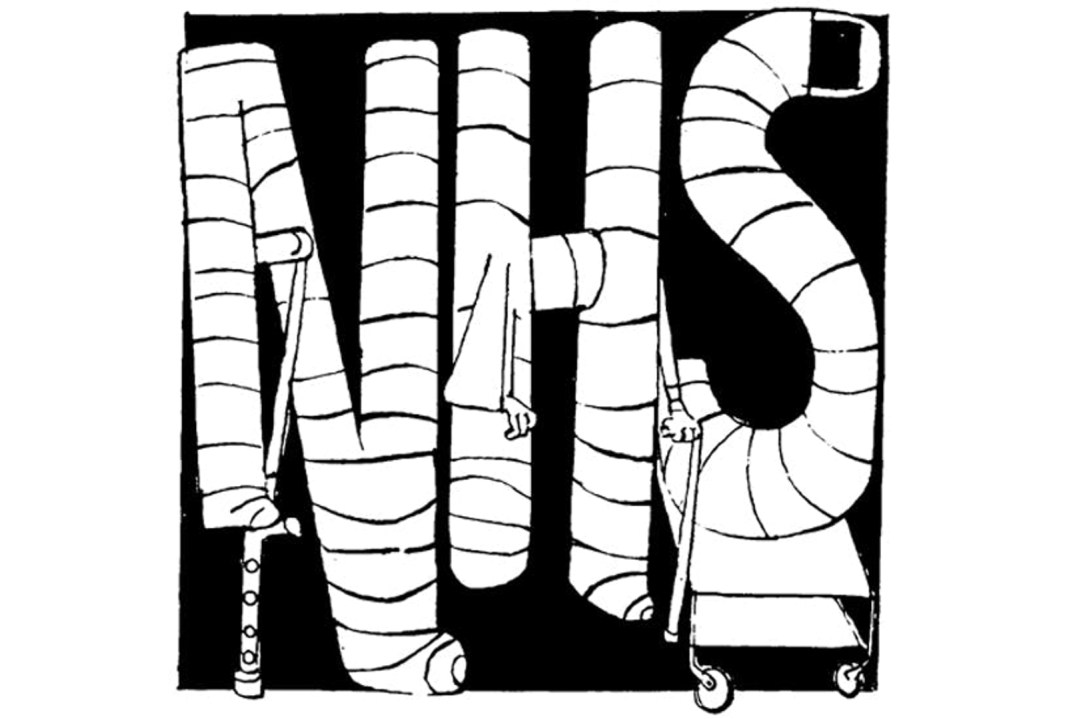

Britain’s ageing health infrastructure comes close to breaking point every winter, but this year something is going to give way. On top of the usual litany of complaints about funding and increasing demand on the NHS from an older population, we can add covid backlogs, waiting times stretching into multiples of nominal targets – and now even the workforce downing tools and walking out.

As usual, the government is going to try to keep things functioning with short-term sticking plasters. There will probably be more millions shovelled onto the ever-burning furnace of the NHS budget, with little to show in terms of patient outcomes. There will, at some point, be a resolution to the issue of staff pay. And then next year, there will be a new crisis. Even if it isn’t at the same level of intensity as this year’s, it will still come, as will the one after that, and the one after that. Until the government is willing to confront the dysfunction at the core of Britain’s health service, the permanent crisis will continue.

The NHS is extremely wasteful in how it uses its resources

The core problem of the NHS is one of resources. You can look at this in two ways; the first is to say that the government simply isn’t spending enough, with the NHS suffering from a decade of relatively low funding. This story sounds a little odd from the outside; spending on the NHS has grown steadily year on year, along with staff numbers. But if you look at it in per capita terms, the UK is towards the lower end of spending in the developed world. This holds even when adjusting for the oddities of exchange rates; we spend around 10 per cent less than the average OECD country, although this adjustment does compress many of the gaps.

This is partly because the UK is surprisingly poor – a country with less to spend per person will tend to spend less per person on health, once again making the point that the actual silver bullet for every problem in Britain is economic growth – but it’s also because of how we spend. In terms of government spending per person, the UK comes out pretty much level with Holland and France, and well ahead of the OECD average. It’s private spending that makes the difference; in the UK this accounts for about 20.5 per cent of healthcare spending. In France, it’s 25 per cent, Holland, 34 per cent, and in Switzerland, a staggering 68 per cent.

This suggests that the problem may be structural; the NHS is the largest employer in Europe, with something around 2 per cent of the British population working for it. It is also a staggeringly large line on the government’s budget – and adding to this means compressing other services, borrowing more, or raising taxes. No matter how many pots and pans are banged together in the street in a pandemic, none of these are innately popular options with the public. The fact that other systems do a better job of mobilising private resources allows healthcare spending to respond to healthcare needs without needing to run through the political calculus of the government of the day.

This disadvantage is exacerbated by the fact that the NHS is extremely wasteful in how it uses the not inconsiderable resources it does have. As one IFS study found, the NHS does very well at being free at the point of use; it’s only major issue was ‘health care outcomes’, which must surely rank very low down the list of priorities for a healthcare system after all. The same paper noted that, while the NHS spent slightly less per person than comparable countries, it somehow managed to translate this into significantly lower numbers of doctors and nurses, fewer hospital beds, and less equipment like CT scanners for them to treat patients with.

As with the issue of overall spending, most of these eventually come down to the problem of running a healthcare system where incentives are provided ultimately by political and press reaction and pressure, rather than by market discipline. One simple manifestation is a constant focus on the frontline; politicians love to announce more doctors and nurses – and we do need more, given the low numbers. But these same leaders are less keen on unveiling a large expansion in the sort of boring bureaucracy that makes the system work. But more bureaucrats is, in many ways, what the system actually needs; doctors spend a significant chunk of their time filling out paperwork, chasing results, and dealing with IT issues. This is an insane use of highly-valuable skilled labour hours; wouldn’t it be better to hire mid-wage assistants to hand these tasks out to? The problem is that freeing up the equivalent of a few thousand doctors in labour hours looks considerably less impressive than announcing the equivalent hires, even if it actually leads to better outcomes.

Another example is the catastrophic lack of investment in capital equipment. The UK not only lags well behind the rest of the developed world in healthcare equipment per worker, it trails behind countries which are substantially poorer. This is not a problem of resources, it is a problem of allocation; the money is there to be spent, but it is being spent poorly.

Both the lack of bureaucrats and the lack of capital result from warped political incentives; the Treasury, keen to keep down overall spending, has encouraged the NHS to raid its investment budget to meet current spending demands, creating a technology debt which grows and compounds year on year, and the political aversion to bureaucracy has made the structure less efficient overall.

So how does the government fix these problems? At this point, the most obvious starting point would be to stop causing them. Moving to a system with significant private involvement like the Netherlands or Switzerland is politically unpalatable; that doesn’t mean that we can’t learn organisational lessons from them. Throwing yet more money at the NHS is a fix with very rapidly diminishing returns; at some point, it will need to be saved from itself.

Comments