Audi will make no more fuel engines after 2035. So that’s the end of the Age of Combustion, signalled by a puff of immaculately catalysed smoke from polished chrome exhausts designed by fanatics in Ingolstadt. But some say the age of motion itself will have shuddered to a halt before then.

A trope of the New Yorker is a cartoon showing cavemen inventing the wheel, a companion to the other trope of desert island castaways. The adventure promised by the wheel and the limitations of boring stationary solitude are ineffably linked. Since Homo erectus left Africa 1.75 million years ago, without wheels, moving our bodies through space has been a defining characteristic of civilisation.

The urge to travel may be, as the biochemist Charles Pasternak says, very nearly innate. But this primal need could be reaching its historical conclusion. Crossrail, if it is ever finished, will be the end of something old, not the start of something new. The Covid crisis proved what had long been suspected: mass commuting is wastefully stupid.

Tom Standage is the deputy editor of the Economist. His subject here is the history of ground transport in all its forms. It is vast and compelling territory to cross. Not for nothing is there a semantic ambiguity about machines that move you: motion and emotion are close.

Instead of the keys to the Thunderbird for your 21st birthday, you now get, Standage suggests, a Lyft subscription

Yet progress in transport types was slow until railways made speed a consumer experience. Smoothness was an innovation too. Reading was impossible in a horse-drawn carriage because the vibrations were so severe. The railway was categorically different. Passengers could enter a reverie on a train journey, numbed by gentle, repetitive sounds — something which Freud noticed and analysed.

And the new railway networks required synchronised timekeeping to avoid collisions, since cities kept different times. Einstein discovered profound relevance here. Train travel also begat wonders of civil engineering. Only the myopic would not compare the synoptic genius of Brunel’s Clifton suspension bridge to the pyramids.

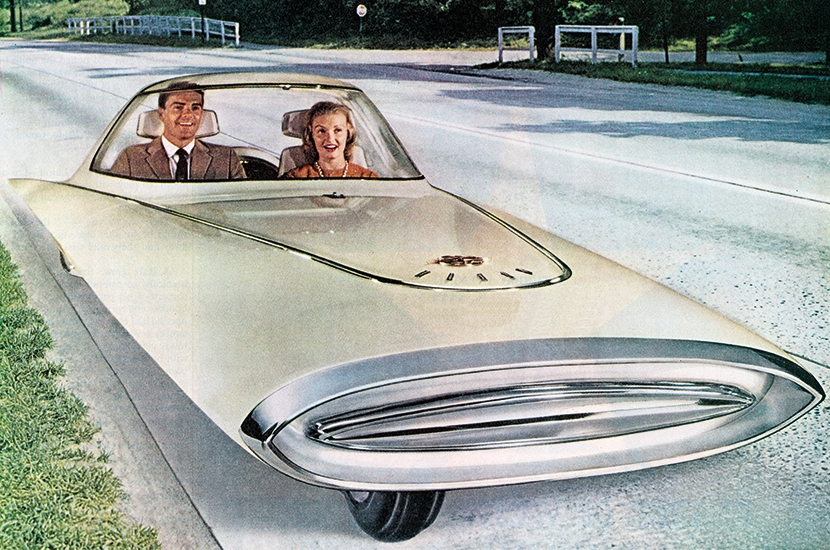

But the car — first the Benz Patent Motorwagen, then Ford’s ‘gasoline buggy’ — brought another sort of democracy to the matter of motion. Selfishness and self-determination were options every new car owner enjoyed. Yet, ironically, Nicolaus Otto’s Viertaktmotor (four-stroke engine) was originally intended for stationary applications. Only when his engine was connected to wheels was the Mephistophelian bargain made: you will be mobile, but enslaved too. The car became man’s most ingenious but also most destructive invention. Yet it provides enduring reference points for our notions of style and prestige. Rock music and the cinema would be much poorer, iconographically speaking, without the automobile.

Meanwhile, driving in central London became irrational a generation ago. The car, which once promised, in E.B. White’s words on the Model T, to ‘enthrone’ us, has become a prison. Within a mile of my house there are eight sets of traffic lights and 20 mph limits, cycle lanes and speed bumps between them. It’s genuinely quicker to walk. In any case, mobility is no longer about covering the ground but about bandwidth.

Inevitably, Standage treats the imminent arrival of the EV, and the autonomous car which will be its handmaiden, as epochal, trumpets-of-Jericho occurrences. But ride–hailing has also disrupted the settled notions of prestige and ownership which have been for so long a part of car culture. Instead of the keys to the Thunderbird as a 21st birthday present, you get, as Standage suggests, a Lyft subscription.

At the same time, e-shopping undermines the rationale of a personal trip to the mall or market. Why use a two-tonne, £100,000 Range Rover to pick up the groceries when a chap on an electric bike will do it for you? There is an answer, but Standage doesn’t offer it.

The nirvana of electricity and autonomy may be as much a present delusion as enthronement and sex appeal used to be. Until we get a zero-carbon grid (and no one is saying when), electric cars simply shift the source of pollution to power stations and Chinese-owned lithium mines.

There will be advantages: autonomous cars in shared ownership will be tireless and never need to rest — thus parking space in cities will be freed up for better use. The problem is that no one has yet written an ethically based code to instruct them. Your Tesla cannot, given the choice, decide whether to mount the kerb and mow down a queue at the bus stop or let you hit a truck head on. No one I know in the business thinks Level 5 — full autonomy — is going to happen any time soon.

A Brief History of Motion

reads a little like an Economist article — not necessarily a good thing — and Standage has not entirely resisted the magazine’s inclination towards the imperial omniscience enjoyed by its normally anonymous writers, fortified here, perhaps, by occasional injections of Wiki erudition — ‘as the Mayor of Brooklyn put it in 1896’.

It is a hybrid book, and so an unsatisfactory compromise. While dutifully describing the car’s role in creating suburbia, and General Motors’ firm but temporary grip on the entire American psyche, it is neither an authoritative history nor an impassioned polemic. It is still less a spirited account of the pleasures and pains of motion, which will both, I think, be with us for longer than anyone suspects..

Comments