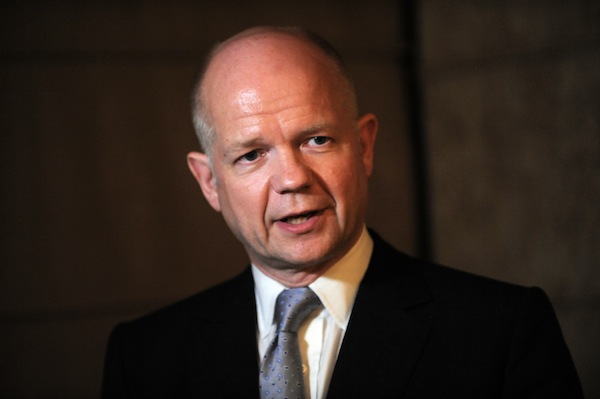

There is a quiet revolution taking place at the Foreign Office under William Hague’s stewardship. This morning’s headlines focus on the announcement of ‘greatly increased’ support for Syrian rebels including £5 million ‘of non-lethal practical assistance’ for the Free Syrian Army. In straightforward terms this means communications equipment, medical supplies, and body armour.

Critics have understandable concerns. Who is the Free Syrian Army? What do they want? Will sectarian bloodshed follow the fall of Assad? Lessons from the Afghan-Soviet war counsel against the promiscuous embrace of rebels whose immediate aims appear to chime with ours.

This is the challenge facing Whitehall mandarins. A humanitarian crisis looms in Syria where more than 80,000 people have been internally displaced. Food shortages exist across the country. Injured civilians are forced to use flyblown field hospitals instead of government ones for fear of arrest.

Navigating the rapidly changing contours of power in the Middle East is among the greatest challenge any Foreign Secretary has faced in recent memory. Finding ways to engage new partners responsibly has forced the Foreign Office to reassess about how it reaches out.

Hague has repeatedly stressed he will not arm the rebels and that the government is cautiously engaging with those it does help. ‘We will, of course, be careful to whom we provide the practical help,’ he told reporters at the Foreign Office this morning. ‘All the support we provide will be consistent with our laws and values.’

Vetting partners on the ground and ensuring the government only works with those who support democratic values marks a dramatic change from the way the Foreign Office previously conducted business. Shortly after 9/11 it created the now defunct Engaging with the Islamic World Group which, at times, intimately supported the work of reactionary Islamists in the Middle East.

This has been done away with, but Hague knows he cannot afford to withdraw from the region. From the rise of Islamists in Tunisia and Egypt, to the chaos in Syria, he has resisted the temptation to engage unconditionally. Partners are now told they must commit to liberal values, particularly with regards to minorities. They will be judged, Hague insists, not on what they say but on what they do. This is the sea-change he has brought to the Foreign Office, linking British support for causes abroad to the maintenance of British values.

Comments