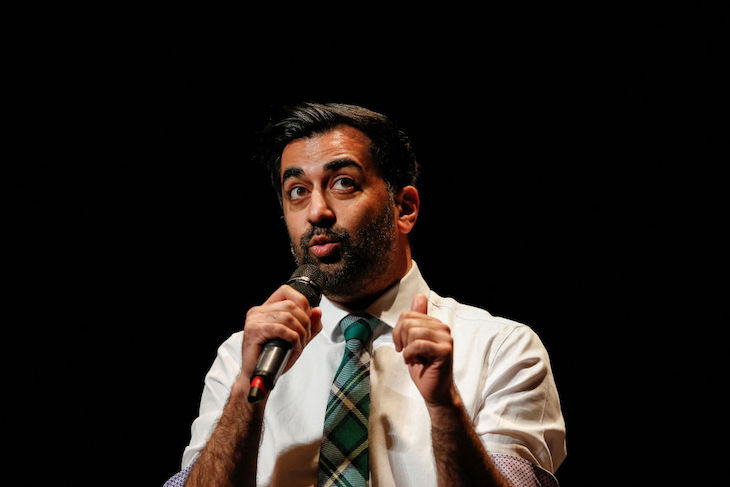

Humza Yousaf, the frontrunner in the contest to replace Nicola Sturgeon, says Scotland could ditch the monarchy if it leaves the UK. ‘I’ve been very clear, I’m a republican…Let’s absolutely, within the first five years (of independence), consider whether or not we should move away from having a monarchy into an elected head of state,’ he told the National.

Yousaf is seen as the SNP’s continuity candidate. But his pop at the monarchy marks a sea change from the official line under his predecessor, Nicola Sturgeon: that an independent Scotland should retain the institution. As the coronation of King Charles on 6 May approaches, this difference, with the potential for another split in the party, takes on a more than theoretical interest.

Given the close links between Scotland and the monarchy forged after Queen Victoria purchased Balmoral Castle where Queen Elizabeth II died in September, the cautious SNP stance is understandable. But the republican spirit among radical nationalists is dormant, not dead, and a sacred symbol of their focus is a 150kg rectangular block of sandstone known as the Stone of Scone, or more romantically the stone of destiny.

Fought over by kings, bombed by Suffragettes, stolen or liberated by students: for an inanimate object, the Stone has had a chequered and lively history. Its origins are lost in the mists of time, with myths linking it to Shakespeare’s Macbeth or the Biblical Jacob. What is certain, however, is that early Medieval Scottish kings were crowned sitting on the stone and that England’s King Edward I – or ‘the hammer of the Scots’ as his tomb in Westminster Abbey dubs him – stole it from Scone near Perth in 1296 and took it to Westminster. An attempt was made to return it in 1328, but furious English rioters kept it where it was in Westminster Abbey.

Edward – the executioner of Scotland’s national hero William ‘Braveheart’ Wallace – constructed an oak coronation throne with a special section to hold the stolen stone. From his reign onwards, all English monarchs – which after the 1707 Act of Union meant all Scottish ones too – were crowned on it.

Militant Suffragettes damaged both throne and stone by planting a nail bomb near it in June 1914, and plans were made to hide it from a feared Nazi invasion in 1940. By then a new party – the SNP – had been founded in 1934 to campaign for an independent Scottish state.

The ideological roots of the early SNP differed fundamentally from its firmly leftist orientation today. Indeed, some prominent early members like the poet Christopher Murray Grieve, who wrote under the pen name Hugh McDiarmid, said Scots would have been better off under Nazi rule in World War Two rather than dominated by the hated English.

Another prominent nationalist who fell under suspicion during the war was Arthur Donaldson, who would lead the party throughout the 1960s when the first SNP MP, Winifred Ewing, was elected to Westminster. In 1941, Donaldson allegedly suggested to an MI5 informant that a network of Nazi sympathisers were planning to undermine the war effort. His ambition, according to an MI5 file, was to become a tartan Quisling and possibly lead a collaborationist Vichy-style Scottish government if the Nazis conquered Britain. As a result, he was arrested in 1941 and interned in Barlinnie jail for six weeks – although the SNP has said his release without charge makes it clear the claims about Donaldson were unfounded.

But back to the Stone. On Christmas Day 1950, four Glasgow University students broke into Westminster Abbey intent on restoring the Stone to its Caledonian home. They succeeded in dragging it out from under the throne and got it out of the Abbey, but in the process managed to break it in two.

After more adventures, the Stone was repaired by a Glasgow stonemason, and four months later was left at Arbroath Abbey and returned again to Westminster. The students became Scottish folk heroes and their exploit the subject of admiring films: their leader, Ian Hamilton, became a respectable QC, but remained a fervent nationalist and stood for the SNP in several elections.

Although at the time of the theft the SNP were scoring a risible average of 0.5 per cent of the vote in elections, the stone’s seizure became a milestone in the party’s steady ascent to supremacy in Scottish politics.

In 1996, to mark the 700th anniversary of its seizure by Edward, John Major’s government, seeking in vain to appease the rising forces of nationalism, returned the stone to Scotland, where it now resides in Edinburgh Castle among the Scottish Crown Jewels.

But in May, the Stone will set out yet again on the familiar road to Westminster, to temporarily take its old place in the coronation throne and play its accustomed role in Charles’ coronation. But the invisible sword hidden in the stone still has a sharp divisive potential. As the most contentious symbol of an age old struggle, it still has its part to play.

Comments