Teenage obsessions are a strange and terrible thing. How, exactly, does an album – which is, after all, nothing more than a recording of some music – seem to embed itself so completely into our

identity? How does it become something so crucially important that we can’t imagine our world without it?

With hindsight I feel rather embarrassed about the effect that Nevermind had on me. I was 14 when it came out. Back then,

kids were divided into “Moshers” – those who liked rock – and “Ravers” – those who liked dance music – and I was, at best, a fledgling mosher flirting with bands

like Guns ’n’ Roses to my great, great shame.

I’d been enjoying the Weird Al Yankovich parody ‘Smells like Nirvana’ on the radio without ever having heard the original song when It Happened. In school, in one of the music

practice rooms, one of the boys had brought in something magical: an electric guitar with a tiny little amp. The first thing he played, and the very first thing I ever heard played live on an

electric guitar was that riff from ‘Smells Like Teen Spirt’. It gave me goosebumps.

That was it. I rushed out, bought Nevermind (on Cassette, obviously) and I was hooked. Suddenly I realised how all the music I’d been listening to before was dominated by sexist,

racist, cork-snorting ‘cock’ rockers, and that this wasn’t compulsory. There was another way.

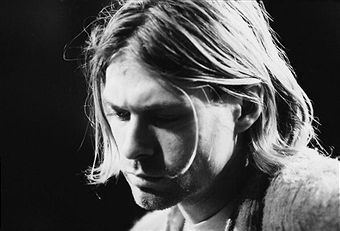

In the cassette sleeve there was a little blurry photo of the band. No internet back then, so that’s all I had. Just that sleeve. Everything I knew about the band was contained within.

Kurt Cobain himself didn’t look like a classic rocker with huge hair and leather jackets. He just looked a bit scruffy, like he’d got his clothes from charity shops (which, it turns

out, he had). He had a singing style that was more about oozing raw, cracked and bleeding emotion straight onto the recordings for the aesthetic effect rather than trying to tell a story or

communicate some message. Songs need lyrics, so Kurt filled his with random fragments of disjointed poetry, loosely tied around some vague theme. The lyrics really, really weren’t the point.

I know all this now, of course, but back then it was nothing more than my life’s mission to understand the buried secrets, to try to work out who this strange man in this strange band really

was. What I felt was that this music was for me. Just me. All the other stuff, that was for other people. This album was mine and mine alone. The sense my teenage brain was making of the nonsense

gave me that sense of ownership, like I was part of some secret club.

This love affair – and that’s how I think of it – lasted a painfully short amount of time. It was always going to be brief because Kurt was a junkie and junkies die, but I never gave up

hoping that Kurt would somehow survive. He didn’t.

When it happened I was stricken with grief. Literal, actual, sickening grief. I understood what “the day the music died” actually meant from then on. How could any music – mere music –

compete with the complex psychodrama that was my relationship Kurt Cobain and Nirvana? How could any other artist or band write music that would induce the same goosebumps and giddy excitement that

Nevermind had achieved in my naive 14 year old mind?

In the end I had to stop listening to Nirvana’s music. It became too painful, too sad and then, later, it began making me angry knowing that such a pointless tragedy had been allowed to

happen at all. It took another 5 years before I started finding music I enjoyed again, and I found it in the most surprising places once I looked beyond the world of rock bands and guitar music,

but nothing has ever obsessed me in quite the same way. It’s simply a question of adjusting expectations.

That’s why, on the 20th Anniversary of the release of Nevermind I couldn’t listen to this album. It’s over. We’re through. I’ve moved on. To celebrate the

20th Anniversary of Nevermind I’m going to listen to Surfer Rosa by the Pixies. It gives me…

goosebumps.

Comments