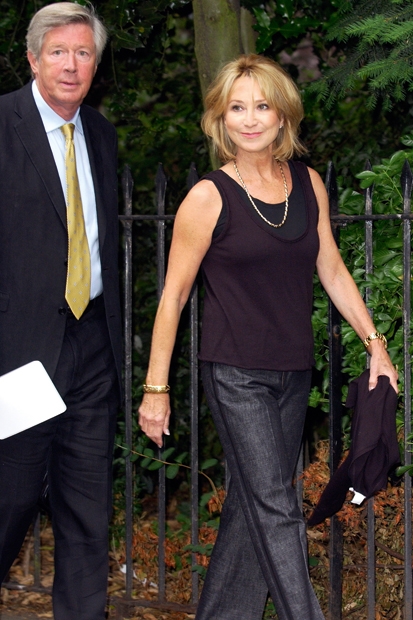

At the age of 75, the theatre director Michael Rudman has got around to his memoirs, their title taken from the mouth of Willy Loman in Death of a Salesman, the play in which Rudman once directed Dustin Hoffman to great acclaim. The author is also Felicity Kendal’s other half, making him a figure of envy for much of male Middle England.

A tall ‘Texan Jew’ who went to Oxford, Rudman has quite a CV. He started at the Traverse in Edinburgh, where with the approval of the theatre’s chairman Nicholas Fairbairn he put on drugs and porno plays. An award-winning stint at the Hampstead Theatre followed, then a spell at the National Theatre. He later ran the Chichester Festival Theatre before going to the Sheffield Crucible.

He’s also freelanced on Broadway and in the West End and one of his theories is that the way creatives behave is usually determined by profit. If a writer or actor thinks someone else is making a lot of cash out of his or her work then toys will invariably fly out of the pram. Put the same person in a permanently broke theatre (like Hampstead), argues Rudman, and everyone is pleasant and grown-up. Art flourishes best where bankruptcy looms.

Rudman reprints in the book a 54-point plan he drafted for his successor at Hampstead. Point 54: ‘Treat every board meeting as if it were your last.’ His stint at Chichester taught him a thing or two: ‘I thought I could deal with the board with charm and jokes.’ They sacked him. So much of directing is about diplomacy, patience and the fraught business of handling superb but tricky actors like Frances de la Tour, John Alderton and the abusive Rex Harrison. As for Dustin Hoffman, most of us would probably have just smacked the tantrum-prone little runt but Rudman hung on doggedly and coaxed an amazing performance out of him.

Halfway through his story, we dive into his Texan adolescence, meeting Rudman Snr, aka ‘the Duke’, who once turned down the offer of a free picture (it didn’t appeal) by an artist he met in Cannes called Pablo Picasso. His mother sounds a character too: ‘When I married your father he looked like a Greek god. Now he looks like a goddam Greek.’ There’s a lot of similar family anecdotage but not enough to be boring.

Rudman doesn’t have a go at critics which seems a bit of a waste. Indeed the sound of scores being settled is curiously absent. How unlike his fellow director Michael Blakemore, who in a gripping recent memoir, repeatedly and horrifyingly plunged the knife into his former boss Peter Hall. Rudman by contrast deals with Hall with admiration and generosity and then moves on. What a relief!

As for Felicity Kendal, their 30-year relationship gets a gallant chapter without beans being spilt. There’s one good story though. Rudman publicly admitted to their suspected affair while directing her in Pinero’s The Second Mrs Tanqueray. Felicity was being very flat in her role in rehearsals. Frustrated, he asked her in front of the cast: ‘I don’t understand why you won’t play the part after all you did to get it.’

The tone of the book is dead casual — so casual that Ian McKellen, Paul Scofield and Shirley MacLaine are misspelled — and the last chapters feel written in a deadline rush. But there’s a good laugh on almost every page. Directors as a breed tend to be clever, nose-picking introverts. Rudman comes across as great company.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £11.99, Tel: 08430 600033

Comments