So Ben Kingsley, or, as he apparently demands to be called, Sir Ben Kingsley, who are you? I’m sitting in a windowless corridor in the Dorchester Hotel, waiting for him. It’s amazingly pink, this corridor. It looks like a cake. He comes out to collect me and he doesn’t look like he belongs here at all.

Perhaps it’s because misery clings to all his famous roles — Gandhi, Simon Wiesenthal, Otto Frank, the sociopath gangster Don Logan, the accountant Itzhak Stern in Schindler’s List. And now he’s neither in prison nor a concentration camp, but standing behind an enormous teapot, looking as Home Counties as a John Lewis valance.

We sit down and I am slightly tongue-tied because I think he’s a great actor, one of the best. His performance in Schindler’s List was astonishing. When I say so Kingsley says ‘Gulp’, very theatrically. Then he goes into a long spiel about how the premiere of his new film, The Prince of Persia, is taking place all over the world today.

The film is awful, as bad as movies get, and I am hoping he’ll roll his eyes, admitting in code how terrible it is, but no, he’s quite serious about pretending this schlock was a great experience: ‘It’s terribly exciting.’ I haven’t bothered turning on the tape recorder for this, but he points at it and says, ‘You can turn it on.’ His body language is relaxed but watchful. His accent is from nowhere.

Ben Kingsley, I know, has two methods in interviews. Sometimes he talks about growing up near Salford in the 1950s. He was called Krishna Bhanji then. His father, the Indian GP, drank and ignored him; his mother, the half-Jewish housewife, accused him of theatricality and ignored him too. He has said, ‘I was not taken seriously. Everything I attempted to articulate was diminished, distorted or interrupted.’ There was also a racist grandmother who hated her Jewish lover so much that she became an anti-Semite.

Sometimes he talks about this and sometimes he just draws on a glittering robe and gives a magnificent display of luvvieness, which is rather touching because it’s brilliantly crafted, but is incredibly irritating nonetheless. When he says, ‘Albert Camus said the only way to understand Iago is to play him,’ I realise I am definitely getting the latter. Damn.

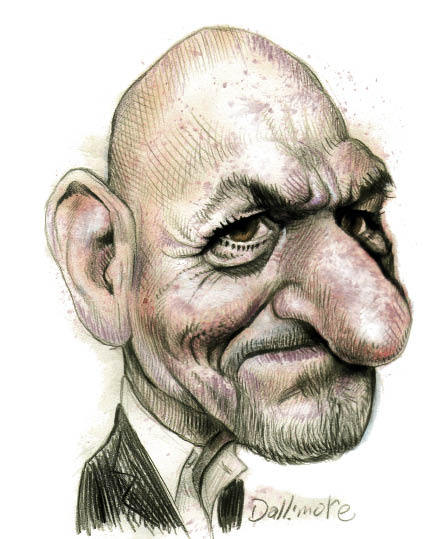

Could he have played the Ralph Fiennes part — the Nazi — in Schindler’s List? ‘Yes, because we have to illustrate with all our might how terrible it was,’ he says in a low voice with an actor’s stare which is straight out of the Actor’s Stare Handbook. ‘In a sense I have the Ralph Fiennes part in this [The Prince of Persia] too.’ He plays Nizam, a bald cartoon baddie with a polished head. So saying he has the Ralph Fiennes part in The Prince of Persia is like saying Tom has the Ralph Fiennes part in Tom and Jerry.

‘Nizam tries to change the map of his universe,’ he goes on. ‘Adolf Hitler did exactly the same thing.’ This is a typical Ben Kingsley sentence: Big Bird is really Stalin. I don’t want to discuss the psychology of tyranny with Ben Kingsley. So I ask: What were your parents like? He gives me a violently calm look. ‘That is very hard,’ he says, ‘because my siblings are alive. We are treading on very dangerous ground. The repercussions could tear through my siblings.’

I’m stuck. So I tell him that another interviewer called him impenetrable. ‘You know I never read reviews, don’t you?’ he says, very conversationally. (Does he think interviews and reviews are the same thing?) She says you are impenetrable, I repeat. ‘I’m sorry,’ he says, ‘I’m sort of listening and not listening.’ He says it so mildly that I don’t realise how cross he is until I play the tape later. But that is often the way — until the tape is played, you don’t realise how much they hate you. I wait for him to fill the silence.

‘It feeds your task of getting me down on a few pages, which is important,’ he says eventually. ‘There are young actors who are going to leaf through this magazine and go, “Oh, let’s see if he is an arsehole or not. Let’s just see. Oh yeah,”’ he continues, still playing a young actor wondering if Ben Kingsley is an arsehole, ‘“I know about that pain. I know about that struggle.”’ So this interview is an act of altruism for young actors. It’s a master-class. At least he told me.

He decided to become an actor at 19, after seeing Ian Holm playing Richard III. He claims he passed out in the auditorium, because of a sense ‘of recognition’. He flunked his RADA audition, where they misheard Krishna Bhanji and called him ‘Christine Flange’, but he got a break at the Royal Shakespeare Company instead. I ask him how he felt when he realised how good he was at acting. ‘Sorry,’ he says, ‘I didn’t understand the question.’ So he doesn’t understand the question and he isn’t listening. I wonder suddenly if I annoyed him when I told him I admired him — if that was when he decided to clam up. Is there ever a moment when you congratulate yourself? ‘Absolutely not.’

And he goes off on another tangent, naming all the theatres in the north that have closed. Interviewing Ben Kingsley is like driving round a ring road, wondering if you will ever find the high street. But at least he is doing an accent now. He is now a northern casting director in the mid-1960s: ‘That was a wonderful audition, Krishna, but we don’t know how to cast you.’ His father said — he is doing his father’s Indian accent now — ‘You are going to have to change your name.’

And the acting — better to talk about the acting — how does it impact on your sanity? ‘It doesn’t frighten me because I’m not addicted to anything,’ he says. ‘If I was addicted to a dangerous substance then I’d be dead. I’d lose touch of where the boundary is and I’d be dead. I know I would.’

I realise I have been staring at a long crease in his head for 20 minutes now. It runs from the dome of his skull to his eye. How did you get that scar? ‘That’s a natural crease,’ he says, ‘that’s not a scar.’ So he minds when I ask about his family but when I ask if anyone ever hit him in the head with an axe, he doesn’t mind at all.

And now you live in Wasp Central, in Oxfordshire. Where do you feel at home? I ask because I am sure that the gifted half-Indian, quarter-Jewish boy is the key to Sir Ben Kingsley, and I want to know where he has gone. ‘What did you call it?’ he asks. Wasp Central. He gasps. ‘That is a terrible thing to say. It’s not Wasp Country. It’s Shakespeare Country. That part of the country gave me my craft and my adoration of the English language. I am more Shakespeare country than LA and the social element is minimal because I hardly ever talk to anybody.’

And he jumps up, shakes my hand and closes the door. He deserved the Oscar — it was for Gandhi — just for playing himself.

Comments