For many years The Spectator employed a television reviewer who did not own a colour television. Now they have decided to go one better and have asked me to write a piece to mark the tenth anniversary of the iPhone. I have never owned an iPhone. (In the metropolitan media world I inhabit, this is tantamount to putting on your CV that you ‘enjoy line dancing, child pornography and collecting Nazi memorabilia’).

But, even though I’m a diehard Android fan, I still cannot help paying attention to every single thing Apple does and says. I don’t think this happens in reverse. I doubt Apple owners pay any attention to the next phone announcement from LG or Nokia — any more than Anna Wintour lies awake wondering what Primark’s autumn season has in store.

How has it achieved this? Well, like De Beers before it, Apple has exhibited a rare marketing genius in creating something that defies the usual rules of economics.

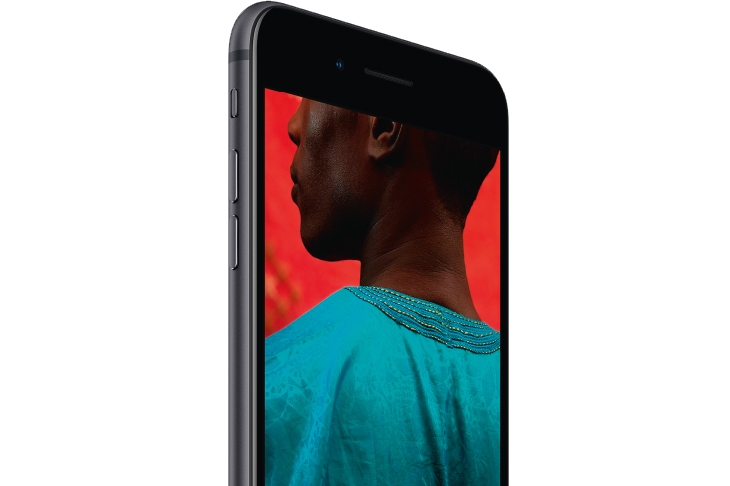

By stubbornly resisting the pressure to chase volume sales by producing cheaper variants of the iPhone, and through fanatical attention to design, Apple has, ingeniously, become a technology company with the characteristics (and the margins) of a luxury-goods company or a high-fashion brand.

On the one occasion that Apple deferred to the bidding of financial analysts and introduced a lower-cost alternative to the flagship iPhone (the plastic-bodied 5C), it failed. Just as there is very little demand for the world’s second most expensive champagne, or for private jets with densely packed seating, there is very little demand for the world’s second-best flagship phone. As someone wisely once said to me, in response to a business proposal, ‘Yes, there may be a gap in the market, but is there a market in the gap?’

Notice that, for the world’s most valuable company, Apple sells remarkably few things. Ring up Samsung, and they won’t just sell you a phone, a vacuum cleaner and a television, they can also build you an offshore oil rig or a supertanker. By contrast, I can name every current Apple product from memory.

But it isn’t only the range that is kept tightly controlled: so, too, is the pace of replacement.

With Apple’s control over both hardware and software, any new product or upgrade is a media event worldwide (Android upgrades take place piecemeal, depending on your handset). Apple’s tempo of innovation is hence kept at a humanly comprehensible level.

Together these two things mean that, once you decide you are an Apple person, choosing an Apple phone is easy — as is deciding when you will next upgrade and to what. For an Android user, the ‘choice architecture’ is baffling: new phones are launching all the time at every different price-point imaginable. Unless you want to spend weeks reading reviews, you can lose the will to live.

It is often the case with super-dominant brands that they possess a superpower that is so strong that we accept it without thinking. It is, when you think about it, a remarkable quality of Coca-Cola that, aside from water, it is the only cold, non-alcoholic drink you can order anywhere in the world without having to think for a second whether or not it is available. You can be in the bar of the Colombe d’Or, a McDonald’s in Taipei, or a beach shack in Belize and, if you ask for a Coke, you’ll get it. If they don’t have it, that’s their fault, not yours. Ask for a Dr Pepper or a ginger beer in those places and you’ll get an ‘I’m sorry, no’ accompanied by an eye gesture that somehow implies that you are a weird idiot just for asking.

Like a fashion brand, Apple’s peculiar magic lies in taste-making. Conventional business logic suggests that you should find out what people want and then provide it to them in volume at as low a price as possible. Apple’s approach is closer to that of an artist, chef or couturier — it exists to inform and improve your taste, rather than to reflect it: ‘It’s not the customer’s job to figure out what they want,’ as Steve Jobs put it.

In some ways, Apple is more like a French brand than a democratic American one. In France, the more expensive the hotel, the more likely it is to refuse to make you a sandwich. There’s only one extortionate prix-fixe menu, but the view from the terrace is so good you’re happy to go along with it.

In the same way, we accept a proprietary charging cable and no headphone jack because the Apple taste-sommelier tells us to.

Apple hence has the extraordinary power to make people accept things they didn’t previously want. No other tech brand can seduce to the same extent. This gives it exceptional power to innovate.

How can we not admire this? The only reason to worry is scale.

Let’s be clear. Humans do almost everything to generate feelings. We don’t have sex predominantly to produce children — or buy Prada sunglasses to protect our eyes from the sun: we do it because of how it feels. Nobody really goes to the bottle bank to recycle glass: we do it for the fun of smashing bottles. Or take those alcohol-based hand sanitisers you get in public lavatories: if asked, you would explain that you are using it to reduce the risk of infection, but really it’s because of the pervily enjoyable sensation you get when the liquid evaporates on your hands.

We do things that feel good, then we post-rationalise. And Apple’s greatest insight is that a phone’s appeal lies less in what we can instrumentally do with it than in how it feels when we do it.

But there’s one important difference. We don’t (well, I don’t) spend five hours a day having sex, buying sunglasses or recycling bottles. There aren’t one-and-a-half billion people spending an hour a day sanitising their hands. Apart from anything else, there’s a time and a place for all these things. But for a smartphone the time and place is ‘all the time, any place’.

When something changes behaviour to the extent the smartphone has done, do we need to ask what the downside may be? (Silicon Valley professes to be improving the world, but is wilfully blind to unintended consequences.) Are 40 billion working hours being wasted every year because it feels better to write on a lovely touchscreen rather than an ugly but functional keyboard? When it is a rainy day in Peckham, how does it improve your life to see pictures of your friends on holiday? When Apple created the smartphone, did it unwittingly create 20 Marlboro in electronic form? Though at least when people smoked they were paying attention to the other people in the room…

Comments