In 1997, the Russian Academy of Sciences gave the names Hermitage 4758 and Piotrovsky 4869 to two small planets discovered 500 million kilometres from earth. The signal honour paid to the State Hermitage Museum and Boris and Mikhail Piotrovsky— its dynastic succession of directors — heralded a new era of post-Soviet expansionism for the former Imperial museum: from now on, the sky would be the limit.

Since then, the Hermitage has opened branches in London, Las Vegas, Amsterdam, Kazan, Ferrara and Vyborg. More than a goodwill gesture, the St Petersburg museum’s overseas expansion has been a way of getting its collections seen. At home in Palace Square there’s room to display only 5 per cent of the three million objects amassed since Catherine the Great started collecting in 1764 — this despite the imperial collections’ subsequent overflow from the Small Hermitage into the Great Hermitage, then the New Hermitage and, after the revolution, the Winter Palace.

Now the collection is on the move again. Since 1999 the museum has been gradually annexing the Eastern Wing of the neoclassical General Staff Building facing the Winter Palace across Palace Square. By 2014, the 250th anniversary of the Hermitage’s foundation, the 800 rooms will provide a new home for the museum’s collections of 19th-, 20th- and 21st-century art.

It’s a bold move, in more ways than one. A glorified office block, Carlo Rossi’s elegant 1830s building is not obviously suited to showing modern art. Frank Gehry, when consulted, declared it a non-starter — the rooms were too small — but Rem Koolhaas came up with the clever solution of roofing over five internal courtyards to create large galleries. Two of the new courtyard spaces are already open. Less is more.

But the building’s architecture is not the only obstacle to modernisation. A more obvious problem is that, apart from the trove of modernist works by Matisse and Picasso acquired in 1948, the Hermitage owns almost no modern art. Malevich’s ‘Black Square’ may have made its debut appearance in St Petersburg in 1913 as the backdrop to the avant-garde opera Victory over the Sun, but it wasn’t until 2002 that the Hermitage got its hands on a ‘Black Square’ of its own. Under Soviet rule the museum was restricted to buying works by Socialist Realist artists, with exceptions made only for the Communist Picasso and the Russian–Jewish Chagall. (To see the art of Malevich, Tatlin and Larionov in St Petersburg you must visit the Benois Wing of the Russian Museum; to see post-Soviet era art, for now, the Ludwig Museum in the Marble Palace.)

The Hermitage doesn’t have deep wells of funding for acquisitions, but neither is it in an unseemly rush to stock up on all the leading western art brands. ‘When you start buying, the museum becomes a player in the art market,’ says Dimitri Ozerkov, the 36-year-old head of the newly created Contemporary Art Department. ‘Money’s not the biggest problem. The problem is having a long line of dealers waiting in Palace Square.’ The collecting policy on Planet Piotrovsky is specifically and patriotically focused on artists whose work reflects the influence of the Russian avant-garde. Rather than genuflecting to the big names in western art, the Hermitage expects western art to pay its respects to Russia.

The plan is to dedicate 12 suites of room to 12 individual artists. The names of Joseph Kosuth, Sol LeWitt and Jannis Kounellis have been mentioned, and one of the 12 will be Ilya Kabakov, whose grande machine of an installation, ‘Red Wagon’ (1991), is already on show in the second courtyard. As Russia’s most famous contemporary artist, Kabakov is an obvious contender, but a better measure of the seriousness of the Hermitage’s commitment to celebrating the Russianness of Russian art has been its choice of Dmitri Prigov (1940–2007) to inaugurate the first of its artists’ rooms in November.

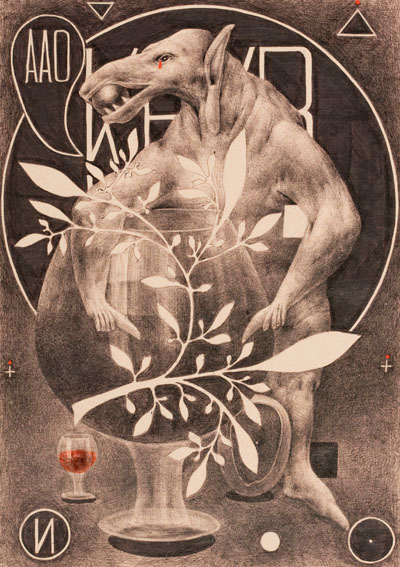

Despite an outing at last year’s Venice Biennale — and an appearance in the Saatchi Gallery’s current survey of Russian art — Prigov is hardly known in the west (though before his death in 2007 he was living with his Russian–Scottish wife in, of all places, Tooting). A founder of the Moscow Conceptualist movement of the 1970s, he developed the charismatic persona of an artist-prophet crying in the wilderness. The principal subject of his attacks was Sovietspeak, of which he had an Orwellian hatred. But unlike the direct actions of Pussy Riot, Prigov’s protests found oblique expression in mini-placards stuck in empty cans, heraldic Biro drawings of sacred monsters, subversive slogans silk-screened on to newspapers and, latterly, videos and sketches for installations, two of which have been finally realised for the Hermitage’s display.

But his chief weapon against official verbiage was words. Socialist Realism had turned art into propaganda; Prigov turned propaganda into art. A voluble poet and legendary live performer — before his death he was planning a recital at Moscow State University while being carried in a wardrobe up 22 flights of stairs — he parodied Soviet public announcements in a stream of satirical addresses and appeals. In 1986, at the dawn of perestroika, he was arrested for handing out spoof ‘Appeals to Citizens’ on the streets and detained in Moscow’s notorious mental Hospital No. 13, before an international outcry secured his release.

A problem with art that relies on words is that it needs translation, especially when the context is as foreign to western audiences as the text. But the Hermitage takes a laid-back attitude to interpretation and seems equally relaxed about mixing cultures. Its current temporary exhibition End of Fun (until 13 January 2013) juxtaposes the Chapman Brothers’ model apocalypses with prints and drawings by Goya, interspersed, for an added frisson, with display cases of antique instruments of torture brought up from the bowels of the collection. When the fun ends the masks and thumbscrews will return to the dungeons, but the Goyas will be coming back to the new wing. On completion of the conversion in 2014, the elegant Rossi interiors will house 19th- and 20th-century art on the upper floors. ‘We don’t want to do white boxes,’ says Ozerkov; ‘we want to put existing art into the palace as it remains.’

Under Communism, the museum, founded by one of history’s greatest consumerists — a woman who bulk-bought Rembrandts to decorate her billiard room — has learned to make do and mend. But it hasn’t lost its imperialist ambitions. Eventually it would like to complete its circuit of Palace Square — Piotrovsky has his eye on the Guards Building next.

Comments