Ysenda Maxtone Graham’s Mr Tibbits’s Catholic School captures the hilarity and pathos of an eccentric headmaster and the unusual establishment he founded in Kensington in the Thirties. A.N.Wilson introduces us to his funny, peculiar world

There are two sorts of school stories. Much the most popular, of course, are those that observe the drama of school life through the prism of the pupils’ imagination. Malory Towers, the Chalet School adventures, Jennings and Darbishire, Harry Potter, Billy Bunter all belong to this addictive genre. My father, who was born in 1902, used to say that the essential thing to realise about such books is that they are really about class; that in his boyhood, it was not the privately educated who were devotees of Frank Richards’s chronicles of Greyfriars, but those who attended ‘government schools’ and liked imagining themselves wearing an Eton collar and being given six of the best in the cloisters.

I am not entirely convinced by this analysis, but I shall return to it. Meanwhile, it is worth noting that there is another type of school story, no less gripping, especially to those of us who have ourselves entered, however briefly, into the strange world of teaching, especially teaching in a private school. These are the stories in which the principal characters are not the children, but the teachers themselves. I am thinking of such masterpieces as Ivy Compton-

Burnett’s Pastors and Masters, or More Women than Men; Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall or, what is in some ways the best of such books, G. F. Bradby’s The Lanchester Tradition, a classic comedy about the liberalising headmaster of Rugby and the torment he caused to his conservative-minded staff.

One of the things brought out by such masterpieces is that almost all those who become schoolteachers, especially in a school for seven- to 13-year-olds, have elected to be seen through the eyes of those who may well idolise or hate them, but will also (especially in England) refuse to take them entirely seriously. They have therefore sacrificed not merely their lives but their dignity — in the words of the scornful father of one of Ivy Compton-Burnett’s characters, they have chosen to ‘humiliate themselves for a pittance’. And yet, two other ingredients need to be mentioned. There is the essential seriousness of their task — teachers of this age group are helping to form and fill human minds. They have far more influence than university professors. There is a truth, which this book makes inescapable, in the old adage that if you have a child at seven you have it for life. There is another, also wonderfully illustrated here: that prep schools are places of hilarity. John Betjeman, later Poet Laureate, and a man who was full of laughter, always used to say that he had never laughed so much as during the year in which he was the cricket master at a small private school near Gerrards Cross.

It is an assemblage of such facts and notions that gives extraordinary pathos and humour to the obese figure of the founder-headmaster of St Philip Neri’s school, Kensington, as depicted in Ysenda Maxtone Graham’s Mr Tibbits’s Catholic School. Ysenda Maxtone Graham is an entirely original imaginative intelligence. As an ardent member of her fan-club, I am perpetually amazed that she is not as famous as Stevie Smith, Jane Austen or Dorothy Parker, for she is one of the great humorists, with an entirely distinctive ‘take’ on the world. Her previous books — The Church Hesitant, a study of the Church of England, and The Real Mrs Miniver, the story of her grandmother, the author Jan Struther — are works of non-fiction, but when I think of them both it is as if I am remembering much loved novels. This is because Ysenda has the passionate nosiness of the novelist. It is also because she knows how a tiny detail can bring a whole character, a whole scene, to life.

The subject of her new book is a small Roman Catholic private school, started in Kensington in 1934 by a man called Richard Tibbits. At first, when I heard this, I assumed that she had made up the surname, but of course, the gods or the muses knew whom they wanted as the author of the book. Without knowing it, Mr Tibbits had been in Maxtone Graham-land all his life, but he waited, like Michelangelo’s slaves imprisoned in marble, until she arrived posthumously with her chisel to make him immortal.

This unusual school history has all the charm and excitement of an Ealing comedy. One of the details that will stay with me forever is Mr Tibbits’s luncheon routines. He had a glass of sherry beforehand and drank red wine ‘with his cheese’, while the boys were munching their way through their spam with mash, tinned spaghetti and other horrors. (Finishing what was on one’s plate was compulsory and if a boy was unable to finish, the entire school was required to wait in the dining-room until he did so.)

This, together with Mr Tibbits’s fearful temper, and his habit of hitting the boys with a slipper (some remembered with a hard shoe) if they did badly in their Latin tests, would imply that St Philip’s was a cruel place. This is not the impression any fair-minded reader will derive from Ysenda Maxtone Graham’s account. In his extraordinary way, Mr Tibbits obviously loved children and was a good teacher. (Another detail I shall always remember is his taking them to swim in the Chelsea baths. He was extremely fat and by this stage wheezy. If any child in the pool got into difficulties, Mr Tibbits, fully clothed, naturally, would hold out a walking stick over the chlorinated waters for their hands to grasp.)

The school was begun in strange circumstances. Mr Tibbits was a member of the Church of England who converted to Catholicism. At the Brompton Oratory one day, a priest remarked that there were no good private schools for Catholic boys in that region of London and Tibbits offered to found one. He bought a house, 6 Wetherby Place, just off the Gloucester Road — and in the early days he did not merely teach the children, he also did the school run, fetching them from their front doors and delivering them back in the afternoons in his rackety old car. Later, as the school grew in numbers, Mr Tibbits married a fellow chain-smoker. It was she who was responsible for choosing the disgusting menus, and she remained, like her brother-in-law and her nephew, who later joined the staff and became headmaster, C of E. It was for this reason that the school began a near quarter of a century’s separation from the Oratory.

There was a strong class element in all this. Class has been an all but unmentionable subject since Nancy Mitford made herself so unpopular by pointing out that the use of such words as ‘looking-glass’, ‘loo’ or ‘chimney-piece’ could be taken as social indicators. Yet, as Maxtone Graham is bold enough to see, you cannot really write a social history of Roman Catholicism in England without grasping the nettle. She does so mercilessly and hilariously.

The dilemma facing many middle-to upper-middle-class converts to Roman Catholicism in the middle years of the 20th century was that they were joining a church which was chiefly composed of the class known as ‘lace-curtains Irish’. These converts, who were usually accustomed to High Church rituals, tended to go to church at the Brompton Oratory, which was founded by and for converts. The educational ‘problem’ outlined by the Oratory Father to Mr Tibbits was not, of course, that there were no good Catholic schools in London, but that there were no such schools for people like the congregation of the Oratory. The years of estrangement from the Oratory are described with especial frankness. An Irish Carmelite became the school chaplain, and he had to put up with such questions from Mrs Tibbits, when a beggar appeared at the kitchen door, as, ‘Is he Irish?’

Many readers of the book — including myself — will feel rather like the little proletarians described by my father who bought the boy’s story paper The Magnet not because they themselves attended schools with cloisters and Latin mottoes, but because they wanted to see how the other half lived. In this case, it is to see not how a half, but how a tiny minority within a minority have lived — the little splinter group of middle- to upper-class Catholic children who needed to be taken to Mass and prepared for First Communion without the faint embarrassment of doing so in the company of those from very differing home backgrounds.

Maxtone Graham’s beady eye sees how revealing are the surnames of the old boys.

The surname ‘Galli’ prompts us to ask: how international was the 1950s clientele? Were the surnames of St Philip’s boys (as they are now) a seductive mixture of exotic European and English recusant, with the occasional modest square English surname thrown in (converts, Anglicans, etc)? It seems as if the answer is yes . . .

Even today, especially among Roman Catholics, the question of class within the English Catholic community causes anguish. This book shows that such anguish is misplaced. Class is an essentially comic thing. And it is only one of the ingredients in this book. What the author has done is to see the school as something like one of the 100 objects through which the Director of the British Museum has chosen to tell the history of the world. By concentrating on this eccentric household in Kensington, with its often anguished staff, and its often amused pupils, she gives us an extraordinary microcosm of what has been happening offstage in the last 70 years, both in the Church and in the world.

Perhaps one of the book’s strengths is its author’s very slight distance from her subject. She is the mother of boys who have attended St Philip’s, and she is also intensely musical. Her descriptions of the liturgy in the Little Oratory and of the value for young people of learning liturgical music are especially telling. At the book’s heart, after all, is the essentially rather serious fact that nearly all the parents who have chosen St Philip’s for their sons have done so because of a set of profoundly held religious beliefs. Maxtone Graham, as a member of the C of E (the ‘Church Hesitant’), is able to feel the ‘Eucharistic elation’ of the school Masses. But she also writes movingly of the science master who lost his faith while saying the Creed. She reminds me of the writer Rose Macaulay, who was able to hold Faith and Doubt in her heart simultaneously. That is an essential ingredient of anything Ysenda Maxtone Graham writes. In the middle of laughing, you often find yourself having a serious thought, or with tears in your eyes.

She is especially sympathetic to the hermit-like retired headmaster David Atkinson, who stepped down in 1989 and who would not be interviewed for the book. She describes how he flatly refused to have a retirement party and threw almost all his belongings, including precious souvenirs, into a builder’s skip before disappearing to the country. His joint headmaster was a young visionary teacher, Harry Biggs-Davison, who took over the headship and has transformed the school into a place of true educational excellence.

Let us end with a truly Maxtone Grahamish piece of trivia which no one else would have bothered to record. We are looking where we are not meant to go — in David Atkinson’s private engagement diary:

Harry [Biggs-Davison] remembers one particular diary entry which gave him new insight into the private habits of his co-headmaster. ‘I was trying to fix up a late-afternoon interview with some parents, and saw that David had written in the diary, “5 pm: S.T. 6 pm: R.F.” I told him I wanted to see some parents in the office but had noticed that he’d booked appointments for those times. “Oh, no, no, no,” David said, slightly embarrassed. “Those aren’t appointments. They’re just something private.” ’

Whom could the initials ‘S.T.’ and ‘R.F.’ stand for, Harry wondered? He was intrigued. It wasn’t until later, when he was flicking through the Radio Times, that he spotted ‘5.00: Star Trek’ and ‘6.00: The Rockford Files.’

If you see the poignancy, and the high comedy of this revelation, then not only will you hugely enjoy Mr Tibbits’s Catholic School; you will have been welcomed into the Ysenda Maxtone Graham world, and the smile will never quite leave your face.

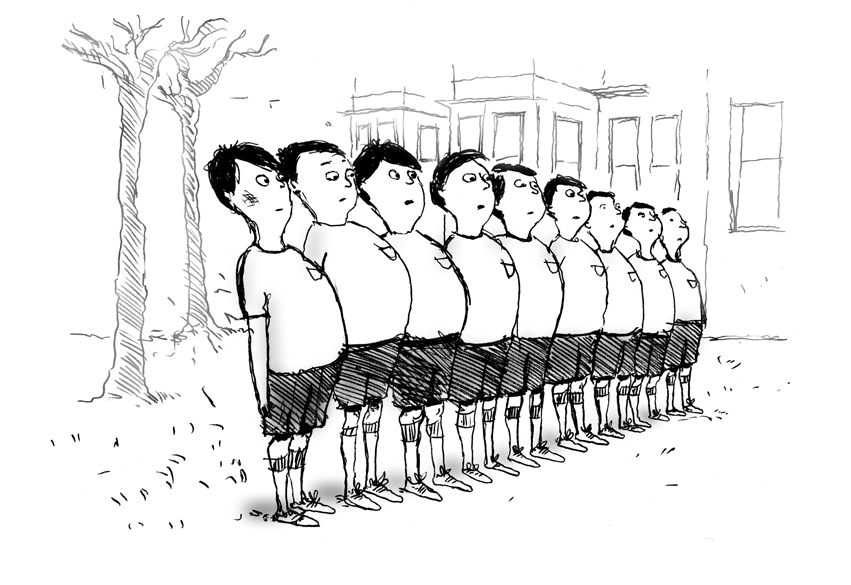

Preface by A.N. Wilson to Mr Tibbits’s Catholic School by Ysenda Maxtone Graham, illustrated by Kath Walker (Slightly Foxed, £15, pp. 199, ISBN 9781906562274)

Comments